Their mass rotted off them flake by flake

from The Sensitive Plant, Percy Bysshe Shelley – circa 1820

Til the thick stalk stuck like a murderer’s stake,

Where rags of loose flesh yet tremble on high

Infecting the winds that wander by.

On June 5th of last year, two weeks after the derecho storm, on the base and surrounding ground of the uprooted old black walnut tree, I discovered many clusters of ink caps. When I first saw the mushrooms, they were just starting and my first thought was, “these are puffballs!” But close inspection revealed that they were just young ink caps heavily veiled and I identified the mushrooms as Coprinellus domesticus. I don’t mean just … I mean COOL! Because according to MushroomExpert these short-lasting saprobes (I’m talking days) have gills that liquefy as the mushroom matures. The ‘ink’ provides the common name for this mushroom, but can also be used as permanent ink for writing or drawing.

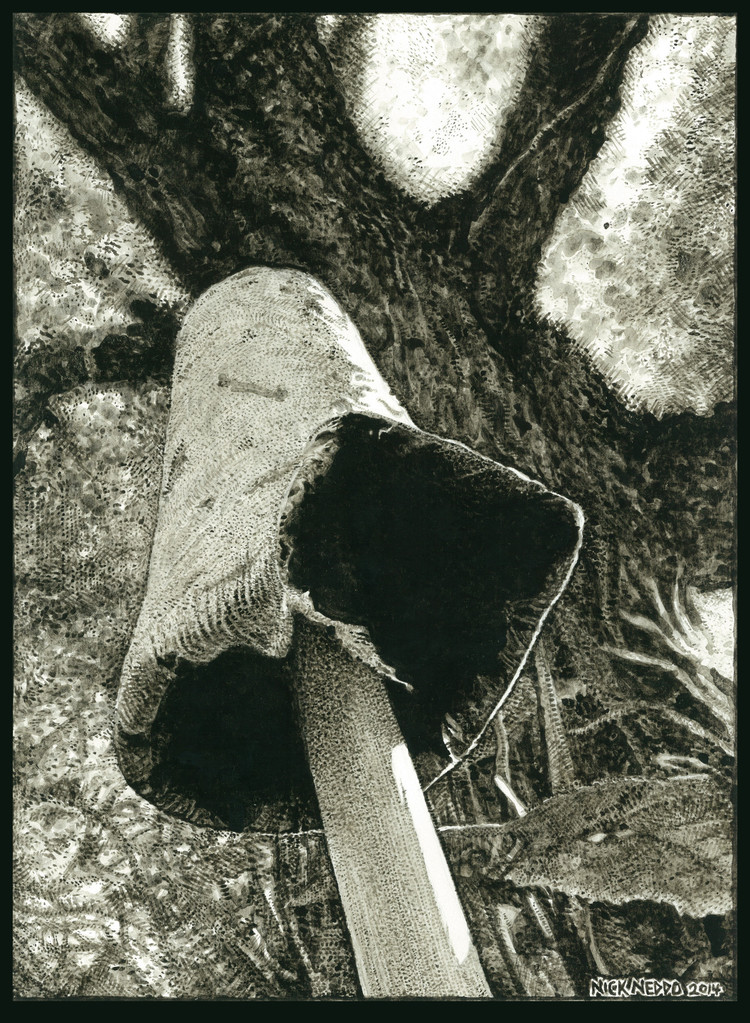

PreppersSurvive gives an easy 5-step process to create ink from an ink cap for writing. Here are the steps: 1—look for some ink caps (they are common); 2—pick half a dozen; 3—wait at least 12 hours; 4—add melaleuca, thyme or oregano oil. Voila! Step 5—get a fountain pen. Nick Neddo warns that during the process of waiting for the ink for form—as the solid, whitish-gray parts of the mushroom transform into black oily liquid—the pleasant earthy aroma evolves into a rather rotten fishy smell. For this reason, some add melaleuca, thyme, or oregano essential oil to help eliminate the smell. Neddo strains the ink solution through a fine-mesh filer into a jar of stinky ink. Neddo describes the ink as dark black-brown and was impressed with its workability and responsiveness. Neddo used a turkey quill pen, bamboo and reed pens and paint brushes for washes.

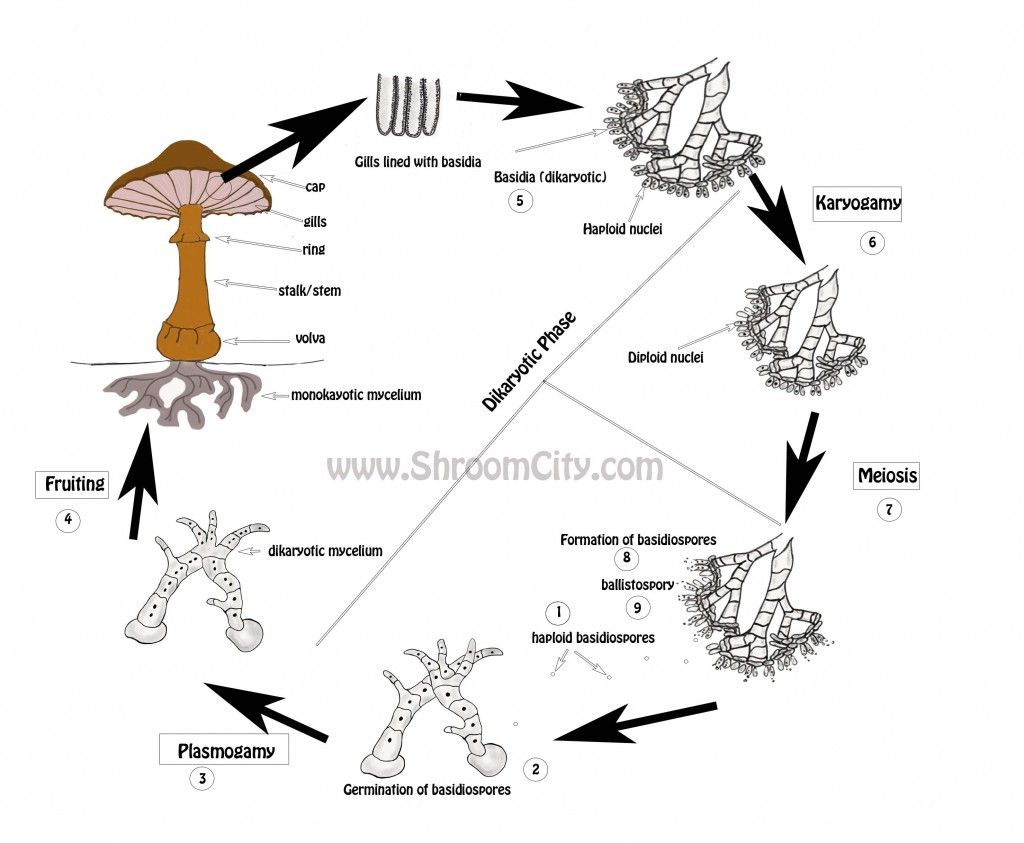

Of course, the ink cap doesn’t have writing in mind when it deliquesces; liquefying its gills from the bottom up as the basidiospores mature and the cap peels up and away to help the spores catch wind currents, is a clever strategy to disperse the mushroom’s young. As the mushroom matures and undergoes the process of auto-deliquescence (liquefaction through self-digestion), the shape of the cap changes from oval (when seen from the side) to broadly bell-shaped and eventually flat. More on deliquescence later. First, some interesting ecology…

Endophytic Fungi & Tree as Ecosystem

C. domesticus is a saprobic fungus that assists in the decomposition of wood, dung, grassy debris, and forest litter. It often grows gregariously and in small clusters on decaying hardwood logs. C. domesticus is also an endophytic fungus: a fungus that inhabits plant tissues without destroying or producing substances that cause an infection to the host cell. It is this endophytic quality of C. domesicus that particularly intrigued me and I wondered if its emergence had anything to do with the derecho that had earlier taken down the black walnut tree. Was there a connection?

Endophytic fungi inhabit numerous types of organisms from mosses and algae to ferns, hardwoods and conifer trees and are estimated to be above a million types. They are universally present in every plant species. Rashmi, Kushveer and Sarma in Mycosphere report that “a single tropical leaf may harbor 90 endophytic species.”

The relationship of the endophytic fungus with its host tree works on a continuum, potentially switching from mutualism to antagonism depending on environmental pressures; the endophyte, for instance, may become saprobic once the host starts senescence.

Endophytic fungi provide several benefits to plants, including protection from plant pathogens and have been implicated in the production of antibiotic and other compounds of therapeutic importance. Endophytic fungi are often a rich source of functional secondary metabolites that include flavonoids, terpenoids, quinines, amines, alkaloids, chlorinated metabolites and aliphatic compounds. Rivera-Orduna et al. in Academia reported Coprinellus domesticus as the dominant fungus living in the roots, branches, bark and leaves of the Mexican yew. They reported C. domesticus in other plants as well. Aghayeva et al. found C. domesticus as endophyte in the bark of the chestnut. Had it been inhabiting this old black walnut tree? Were the roots and the bark of this old tree its ecosystem?

Salazar et al. reported in Lankesteriana that Coprinellus radians was found in roots of certain plants and shown to promote germination of the plant’s seeds. Vieia et al. in the Canadian Journal of Microbiology also reported that C. radians was one of over 200 filamentous endophytic fungi associated with the Brazilian medicinal plant Solanum cernuum and capable of antimicrobial activities. Some endophytic fungi produce similar chemical compounds as its host; others produce novel natural products. For instance, the anticancer drug taxol was found produced by endophytic fungi isolated from Taxus brevifolia, among others. Endophytic fungi can also increase tolerance of its host plant to environmental stresses. For instance, they can increase drought and disease resistance of the host plant and decrease herbivory and certain pathogens.

The How and Why of Deliquescence

Like most ink caps, Coprinellus domesticus is an umbrella-shaped agaric whose gills deliquesce or autodigest as the mushroom ages. It all starts with rain, the driving factor, writes Cass Fuentes with the Fungus Federation of Santa Cruz; growing with enough force to burst through solid concrete, the ink cap absorbs moisture from the atmosphere and expands. In their article Dish of Deliquescence, Cornell University shares that “the mushrooms appear in wet conditions, but then the same moisture that brought life to the new tissue facilitates death: the inky caps digest themselves via hydrolytic enzymes, tiny biologic machines that use water to break down molecules. The slopfest takes just a few hours, from pileus to puddle.” Why does the ink cap auto-destruct into an inky puddle of goo? Fuentes suggests that because the gills are so tightly packed together, dispersal via wind currents need help; auto-digesting its own cap exposes more gill surface. This notion is supported by the fact that auto-deliquescing starts from the bottom of the cap and moves upwards, uplifting the cap margin to create more gill exposure. Cornell rather pithily adds, “It’s a selective-death process that get useless tissue out of the way of the babies, letting them escape to as far from the parent as possible before they begin their new lives (it’s a little like college). As an inky cap deliquesces, the tightly packed gills separate and curl back, allowing some spores to float out into the air.”

According to Cornell, , “About two hours before spore-release, chitinase is made, but only in the mushroom cap and gills, never in the mycelia or stem.” The hydrolytic enzyme chitinase is released from the vacuoles of senescing gills and break down the complex sugar chitin. These enzymes structurally degrade their caps, as their stipe remains upright, supporting a dripping inky mess. Cornell adds, “Deliquescence is a chain reaction [with] auto-digestion releasing a liquid that is a potent digestive. The liquid is taken up by the neighboring cells, which are turned into more liquid, and the wave of destruction travels along the gills just behind the region of maturing spores.” The spores are not digested by this enzyme, and may use the dripping ink as another mode of dispersal with the washing of the rains.

Deliquescence is essentially an efficient way for the ink cap to open-up gills, get tissue out of the way and release its young. This self-sacrifice in the reproductive process is quite common. See my article on the Mayfly Dance, the 24-hours in which mayfly adults emerge, swarm, mate, then lay their eggs and die. Cornell shares the notion that the praying mantis male allows itself to be eaten by the female after mating as a form of self-sacrifice to provide nutrients to the mother and her eggs. There is, of course, the heroic journey of the wild salmon to its original spawning grounds, where, all its energy spent, the salmon lays and fertilizes its eggs before succumbing to exhaustion and death. “Ink caps transport all their sugars out of the fruiting body and into their spores just before sending them off. By the time deliquescence begins, there’s virtually no food left in the cap or gills; it’s all gone to the spores.”

Stages of Ink Cap Growth and Deliquescence

Day 1: Two weeks after the storm over the span of three days, I observed how this mushroom colony first appeared and evolved from solid firm tan-coloured balls to black inky mush. The caps began as closed ovals of a warm honey yellow colour, enclosed by a universal veil in varying stages of fragmentation. They resembled puffballs.

Day 2: The next day, they opened up, some in the shape of a rolled-up umbrella, others with caps (pileus) expanded to a convex or conical shape. Still honey-yellow to brown but paler at the edges, the expanded caps now had ‘warts’ on their surface, whitish to brown left overs of the universal veil that could easily brush off. Some mushrooms had started to go gray with a brownish centre. The caps were finely grooved beneath the whitish to brownish fragments of their universal veils. The gills looked white when the mushrooms first opened up but soon turned grey. (On the third day they would turn blackish and deliquesce into black “ink”). Their radial furrows or striations became more apparent.

Day 3: It rained much of the night. On the third day, when I visited the mushrooms between downpours, they had completely opened-up into the typical ink cap convex shape. They had gone gray with black ink-dripping edges and the veil fragments had washed away; the caps looked sleek with more prominent grooves. Several had totally liquefied (deliquesced) and collapsed. On touching one, my hand was covered in ink. The timing, I thought, was impeccable. Ink caps produce an enzyme that eats their bodies and as the inky slime gets washed away in the next rain, along with a bazillion zygotes, the spores released through tissue digestion are then exposed to air currents or washed into the ground with the ink. They may also dry with the liquid on the mushroom to be later wind dispersed. Insects that land on the liquid mass—or someone’s hand—also help disperse the spores.

From Endophyte to Saprophyte…

Coprinellus is an incredibly fascinating mushroom. Ultimately, the ink cap is fast and efficient. The fruiting bodies burst out of the ground or rotting tree following a moist rain, formed great colonies of mushrooms that matured as though they knew when it would be perfect for the dispersion of their spores and just when the big rains came they did what they needed to do—their caps liquefied in a process called deliquescence and spread their inky substrate full of spores in the rains—then collapsed back into obscurity. All within three days.

Did the Coprinellus fungi escape the black walnut when the storm toppled it and change from endophyte to saprophyte, like a smart adaptive fungus? Changing its operative mandate with the changing environment?

I saw large strips of bark scattered on the ground at the base of the tree and that is where I saw a concentration of Coprinellus (beneath the bark strips on the ground and on the bark of the tree base); bark is one of the tissue types known to harbor Coprinellus. Was the fruiting stage induced by light? The toppled trees certainly opened up the canopy.

Many basidiomycetes need certain conditions of light to complete their life cycle; for instance, Coprinellus domesticus requires blue light, at an intensity of 1.5-3 x 104 erg/cm2 sec-1 and 7-9 days of light to produce the mature basidiocarp. Light is known to induce fruiting and asexual sporulation of the dikaryon stage of other endophytic fungi.

In a sudden moment of clarity, I saw how fungi interconnect all things on this planet, living in, on, above and below everything. First helping it fully live, then helping it efficiently die. Fungi literally stitch a living tapestry of balanced tension between symbiosis and antagonism, all orchestrated by the environment and climate–and completing a cycle that has marched on for millennia. With that realization, I felt very small, but connected and part of something huge and truly awesome.

When you tug on a single thing in nature, you find it attached to the entire universe.

John Muir

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

One thought on “When an Ink Cap Inks Its Way to Goo Freedom…”