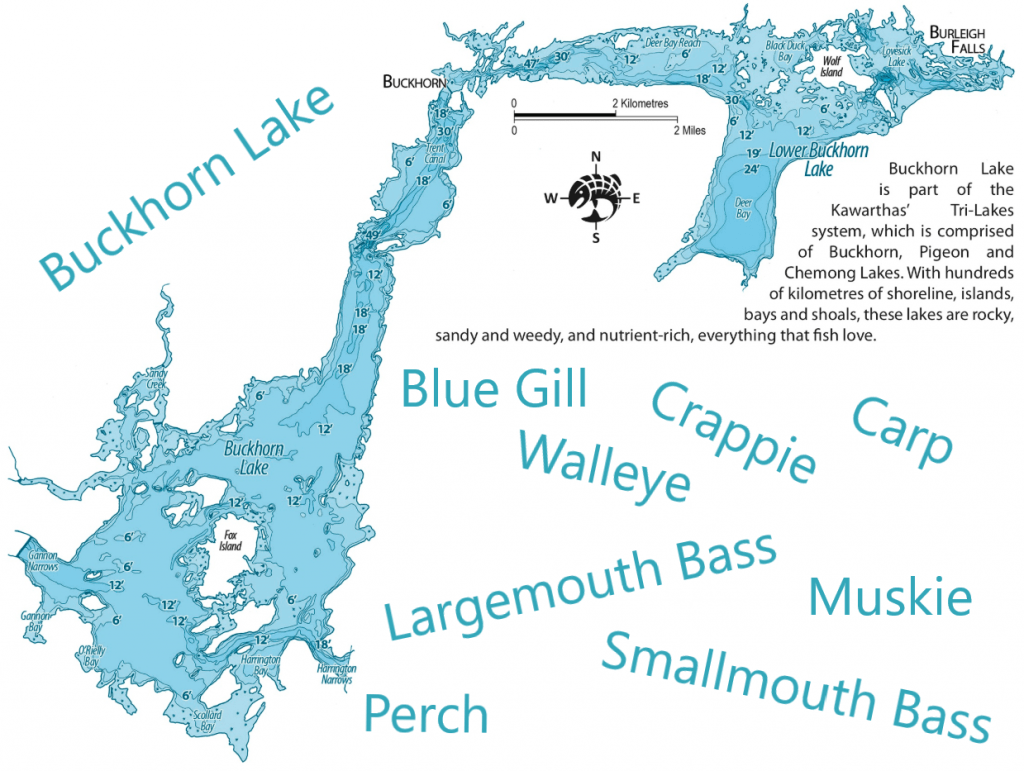

A short time ago I visited the village of Buckhorn, located in the beautiful cottage country of the Kawartha Lakes Region. The town wraps around Lock 31 of the Trent-Severn Waterway, between Upper (main) Buckhorn Lake and Lower Buckhorn Lake, which feature rocky Canadian Shield shorelines and rocky islands.

Buckhorn Lake is part of the Kawartha Lakes network and lies on deep fertile soils deposited by glacial activity on top of limestone and shale bedrock. Its primary inflow comes from Pigeon Lake, flowing in from the southwest side through Gannon Narrows and Chemong Lake via Harrington Narrows. Buckhorn Lake then flows via the dam at Buckhorn into Lower Buckhorn Lake

I’d driven north from Peterborough through Bridgenorth and now wanted to loop southwest via Lakehurst, Oak Orchard and Gannon Village on the 37/16. The drive took me to the lake’s southern-most shallow end, where I canoed through the open wetlands of the lake. Both Lower and Upper (main) Buckhorn lakes are shallow for glacially-formed lakes—average depth is 3.5 m for Lower Buckhorn Lake and 2.1 for Upper (main) Buckhorn Lake. And how different the south part of Buckhorn Lake was!

History of Kawartha Lakes

The Wisconsin glaciation that covered virtually all of Ontario in up to a two-kilometer-high ice sheet formed the Oak Ridges Moraine about 12,000 years ago. According to Frederick M. Johnson the advancing and retreating ice sheet “plucked large quantities of this soft bedrock material and ground it into finer gravel, sand, silt and clay-sized particles. Large depressional areas were scoured out of the bedrock. These depressional areas became today’s lake basins such as Lake Simcoe and the Kawartha Lakes.”

Glacial ice blocked release of glacial meltwater, creating the large glacial Algonquin Lake to the north of the Oak Ridges Moraine. As the Laurentide Ice Sheet finally retreated, the Oak Ridges Moraine blocked previous drainage valleys of the giant glacial Lake Algonquin; but water found a way to drain. As the valleys overflowed, the currents carved new spillways, ultimately creating the Kawartha Lakes.

Although lakes on the more northern Precambrian Shield tend to be deep and rocky bottomed basins, the Kawartha Lakes—including Buckhorn Lake—are located on Paleozoic glacial deposits and have shallow basins of mostly flooded land. The deepest part of Buckhorn Lake, for example, is restricted to a small region by the dam at its most northern end. The remainder of this dendritic lake ranges from 1.8 to 3.6 metres, averaging 2.1 m. Bays and shoals on its southern and western shores are marshy, very shallow with a soft bottom and weedy.

Buckhorn Lake’s History of Eutrophication

The current Buckhorn Lake was created in 1830 from mostly river and wetland when early settler John Hall built a sawmill and dam at the community of Buckhorn on what is now the northern tip of Buckhorn Lake at the narrows leading to Lower Buckhorn Lake; the dam and lock later became part of the Trent-Severn Waterway that linked several Kawartha Lakes including Balsam, Cameron, Sturgeon, Pigeon, Buckhorn and Chemong lakes. The waterway connects Lake Ontario at Trenton to the Georgia Bay part of Lake Huron at Port Severn.

Construction of the waterway started in 1833 at Kawartha Lakes and took 87 years to complete. The flooding virtually eradicated the wild rice (mnoomin, meaning good grain) that flourished in the shallows of the original waterbodies in the area and used by the local indigenous Anishinaabe peoples.

Buckhorn Lake was originally known as Hall’s Bridge and has at its northern tip the small village of Buckhorn (named after John Hall’s collection of deer antlers, displayed on the outside walls of his mills). At that time the population of Buckhorn was 50 people. Timber became the chief industry and export in the area, with ship’s masts, shingles and barrels shipped down the Erie Canal to New York. Much of the area became cleared since then and cottagers have moved in, slowly occupying more and more of the lake’s shorelines. Development with associated stormwater runoff, faulty septic inflow, erosion from bank modification and lack of natural wetland buffer have all contributed to the advanced eutrophication of the lake. While eutrophication (increased nutrients and productivity of a lake) occurs naturally, its rate is often accelerated by human activities, which is occurring in Buckhorn Lake.

In their 1976 report the Ministry of the Environment considered Buckhorn—along with Pigeon, Chemong, Clear, and Stony lakes—a meso-eutrophic lake (fairly rich in nutrients). It averaged 2.3 m deep in 1976 but is a more shallow today, fifty years later. A look on the map shows Buckhorn as highly convoluted and dendritic, with a main basin (maximum depth of 6.7 m) and smaller but deeper nameless basin with maximum depth of 14.7 m in 1976 where the dam is located. This has also changed; the deepest part of the lake (aside from the northern tip at the dam) is a narrow neck leading to the dam of 5.7 m, which is 1 metre more shallow from 1976 (and the only area of the lake lacking macrophytic growth; see Figure 4). The remainder of the lake measures 3.6 m or less in depth. The surface area of the main lake in 1976 was 32.3 km2 and volume was 7.42 x 107 m3. The main lake contains a series of shoals that form a string of islands, formed by diagonal trending Shield rock knobs. Most of the islands are Indian Reserve land, belonging to the Curve Lake Reserve. The lake’s pH measured from 8.0 to 8.4 in 1976, slightly alkaline and typical of a eutrophic lake.

In 1976, Buckhorn Lake had moderate concentrations of major ions, phosphorus (22 to 23 µg/L) and chlorophyll a (4.2 to 6.3 µg/L) and Secchi disk clarity of 2.3 to 2.4 m suggests a large littoral zone (where one can see to the bottom), given the lake’s current average depth of 2.1 m. The Ministry of the Environment observed average phytoplankton biomass ranging from 1.6 to 3.3 mm3/L, consisting of a heterogeneous assemblage of taxonomic classes with bloom conditions frequent. In 1976, phytoplankton in Buckhorn Lake consisted of mostly diatoms (50 to 63% of biota biomass) followed by blue-greens (20%) with remaining percentage composition by Chrysophyta, Chlorophyta, Cryptophyta and Dinophyta. Zooplankton in Buckhorn Lake were represented by mostly cyclopoid copepods and cladocerans.

In the 1970s, only Rice, Scugog, Bay of Quinte, and Sturgeon lakes were designated highly eutrophic. These were characterized by high concentrations of major ions, phosphorus (>30 µg/L) and chlorophyll a (>6 µg/L). Phytoplankton biomass ranged from 4.8 to 23.6 mm3/L and was dominated by the Cyanophyceae (blue-green algae) and the Bacillariophyceae (diatoms). Calanoids were rare and cladocerans abundant. Already in 1976, land drainage was recognized as the largest source of nutrient loading to all Kawartha Lakes, including Buckhorn Lake.

Brief Introduction to Eutrophication

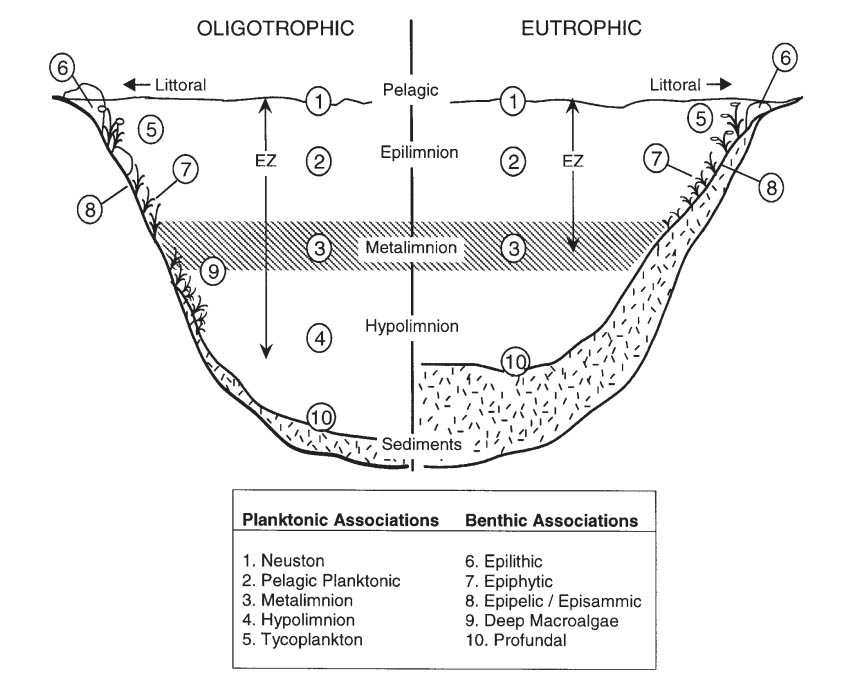

All lakes, as they age, undergo a process called eutrophication: increased productivity with added nutrients over time. Levels of biologically useful nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen dissolved in the water of a lake determine its trophic (nutritional) status. When these limiting nutrients increase, higher plant growth is triggered and eutrophication takes place. Lakes are typically classified as oligotrophic, mesotrophic, or eutrophic based on their trophic (nutrient) status.

Oligotrophic lakes are typically young and cold lakes, low in productivity with high water clarity and well-oxygenated. With time, such a lake will gain nutrients, fill in, warm, and evolve into a mesotrophic lake. A mesotrophic lake will, in turn, evolve into a eutrophic lake, which will evolve into a bog, marsh or terrestrial environment. This is a natural process that occurs over time.

Mesotrophic Lakes have an intermediate level of productivity; these lakes have medium-level nutrients and are usually clear water with submerged aquatic plants.

Eutrophic Lakes have high levels of biological productivity. Plants are abundant due to available nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen. Fauna initially increase with increased plant and algal production, but eventually reduce when algal blooms overcrowd the lake and deplete the oxygen through decomposition.

Hypereutrophy occurs when human interference results in excessive nutrient loading and accelerated plant and algal growth. This increases the rate of eutrophication beyond its natural rate. Hypereutrophic lakes typically have visibility lower than a metre; they contain over 100 µg/L of phosphorus and more than 40 µg/L of total chlorophyll (algal) biomass in the water. The overgrowth of algae removes oxygen and suffocates all fauna, creating dead zones.

Cultural or accelerated eutrophication occurs when inputs from fertilizers, sewage, industrial waste water or other sources of nutrients are introduced by human sources; this leads to excessive plant and algal growth and potential oxygen depletion.

Aquatic Plants in Buckhorn Lake

In a 1972 survey the province identified Tape Grass (Vallisneria americana) and several species of Myriophyllum as the most common plants in Buckhorn Lake, forming dense and extensive macrophyte beds. These extensive macrophytic growths created severe impediments to recreational use.

“In Buckhorn Lake the vegetation formed dense impenetrable beds which covered some 2800 ha or about 85% of the lake area. Based on a brief visual assessment, the vegetation was largely dominated by Myriophyllum spp (tentatively identified as M. spicatum) although Vallisneria Americana, Najas flexilis and Potamogeton strictifolius were also common.”

Ontario Ministry of Environment, 1976

The southern end of Buckhorn Lake is currently very shallow and remains extensively covered in weeds (over 90%).

During my brief paddle along the southern end of the lake, I identified submerged, floating and leaf-floating plants, listed in Table 1. All identified aquatic plants are common in eutrophic, nutrient-enriched, shallow lakes of the Kawartha region. Unlike the northern oligotrophic lakes of the Canadian Shield, the Kawartha region lakes are naturally more productive and support distinctive eutrophic communities adapted to higher nutrients in the soft sediments and the water with a high proportionate littoral zone (light penetration to the bottom).

Table 1: Floating and Submerged Aquatic Plants Identified in the south end of Buckhorn Lake

| Aquatic Plant | Designation | Description & Habitat |

| Ceratophyllum demersum (Coontail) | Abundant | Floating plant with no roots, leaves 1-3 cm long, whorled on stem 5-12 per whorl, tiny serrations on leaves feels rough to touch. Found in waters up to 7 m deep. Grows vegetatively from small fragments |

| Vallisneria Americana (Tape Grass) | Abundant | Common, native and abundant in the Kawartha Lakes. All leaves originate from one point on the lake bottom, veins darker/meatier in the centre of the leaf. Plant spreads by underground roots and often connected to other plants. |

| Nymphea odorata (Fragrant Water Lily) | Abundant | Round 7-30 cm long leaves with V-shaped split and pointed lobes, thin stems attached to rhizomes in sediments, white fragrant flower floats on surface |

| Nuphar variegata (Yellow Pond Lily) | Abundant | Heart-shaped leaves with rounded lobes, stems flat on one side and grows from rhizome in sediments, yellow upright flower usually above water |

| Elodea Canadensis (Canadian Waterweed) | Common | Perennial herb, bright green, with stiff leaves in whorls of three all the way up stem, leaves small (1.2-4.5cm) become crowded towards tip. Forms thick mats on the bottom of the lake, grows to surface if sufficiently shallow. |

| Myriophyllum sibricum (Northern Water Milfoil) | Common | Leaves that resemble feathers and whorled along the stem, leaf whorls spaced apart on the stem leaving much of the stem exposed. At the tip of stem, whorls become bunched and take on a “knob-like” shape. Stem and tip of branches showing red colour later in summer. |

| Ranunculus longirostris (Water Buttercup or Crowfoot) OR Cabomba caroliniara (Fanwort) | Common | Small leaves. A sheath wraps around the base of the leaf where it joins at the stem. Contain poisonous, anti-bacterial substances used by native people as an antiseptic and anti-cancer treatment. |

| Utricularia vulgaris (Common Bladderwort) | Common | Free floating plant without roots, floats just below water surface, leaves up to 5 cm and dense toward stem tips, finely divided into leaflets, small yellow flowers on erect reddish stems over water |

| Potamogeton nodosus (American Pondweed) OR Potamogeton amplifolius (Bass Weed) | Frequent-Common | Large brown, wavy-edged submersed leaves with large parallel veins. Floating leaves also present later in the season; these are elliptic, leathery and waxy on the upper surface. |

| Brasenia schreberi (Water Shield) | Rare | Perennial plant in slow moving water with thick coating of gelatinous slime covering the young stems and underside of leaves; stems attach at centre of oval-shaped leaf that floats on surface. |

I did not identify some of the plants found in the 1972 Ministry survey reported in 1976: Myriophyllum spicatum (Eurasian watermilfoil); Najas flexilis (Nodding Waternymph); and Potamogeton strictifolius (straight-leaved pondweed, an uncommon plant found in alkaline waters). However, I did observe abundant Tape Grass (Vallisneria Americana), also seen in abundance by the Ministry in 1972.

Controversy over Wild Rice Planting

Cottagers on Buckhorn Lake are concerned that wild rice is being planted by local First Nations in Buckhorn Lake just as was being done for decades in Pigeon Lake, reported by the CBC in 2018. Rhiannon Johnson with CBC reported, “At the heart of the dispute is the wild rice plant, which Anishinaabe call mnoomin, meaning good grain or seed, and it has been a staple of their diet. In the early 1900s, flooding of the water systems through the Kawarthas with the completion of the Trent-Severn Waterway almost eradicated the wild rice in the area.”

The lack of access to this traditional food source was one of the reasons James Whetung set out to restock the lakes with wild rice more than 30 years ago. “I went and talked to the Elders and they told me where all the wild rice used to grow,” he said. “There was none there at the time I started planting seeds so I wanted to help rejuvenate our culture.”

“The presence of wild rice is a positive indication of the overall health of the ecosystem,” says Karen Freely, communications and acting indigenous affairs officer for the Ontario Waterways Unit of Parks Canada. James Conolly, an archeologist at nearby Trent University who is studying the environmental history of the Kawartha lakes area said the lake is going through a process of re-wilding after more than a hundred years of farming and logging in the area. The geographic area that Pigeon Lake [and Buckhorn Lake] sits on was once a creek surrounded by wetlands, according to Conolly. “[The cottagers] didn’t realize it, but they bought a wetland,” he said.

Tape Grass or Water Celery (Vallisneria Americana) is a native plant commonly found in the Kawartha Lakes in abundance. I observed the tape grass in shallow areas from less than a metre to several metres deep, such as the southern-most part of the main lake. Collected samples had ribbon-like leaves coloured from green to reddish with a distinctive darker, meatier ribbed vein in the centre; this matched the description for Tape Grass (KLSA, 2009). Wild rice plants do not have this distinctive feature in their leaves. They also prefer more shallow water (e.g. 15-90 cm of water). I would have expected to see flowering stalks by this time; it was too early for seed heads, which turn brown to purplish in colour by Labor Day.

It is likely that wild rice still exists in Buckhorn Lake, given that suitable habitat exists in the lake and Wild Rice was seeded in Buckhorn Lake starting in the 1990s. I just didn’t see it. Tape Grass is an abundant native plant throughout the Kawartha Lakes region and found in Buckhorn Lake in abundance since the 1970s.

Two reasons suggest why Tape Grass is more abundant and successful in the lake than Wild Rice and that Tape Grass is likely taking over shallow areas of the lake: 1) Wild Rice plants grow from seed while Tape Grass grows primarily vegetatively through rhizomes, giving it a competitive edge over the annual wild rice that grows only from seed; 2) high turbidity (from stirred up bottom sediment by boaters and waves and from algal clouds) favours Tape Grass over Wild Rice, which prefers higher water clarity. While the copious zebra mussels in the lake tend to increase water clarity to the benefit of wild rice (which prefers more clear water), nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen from residential and agricultural runoff are doing the opposite, and favouring Tape Grass.

Algae in Buckhorn Lake

In the south part of the lake, particularly Scollard Bay and its channel, I spotted clouds of cotton-candy-like algae loosely attached to or tangled in the submerged and floating weeds. Excessive phosphorus and nitrogen in the water encourages the proliferation of cotton-candy-like algae in spring, summer and fall. The weeds catch silt and organic debris to form a complex productive community of mostly filamentous green algae (Microspora, Mougeotia, Zygnema and Spirogyra) in a loosely associated mesophytic community that includes diatoms, Chrysophytes, bacteria, fungi and blue greens. I brought a sample of the surface algae home and investigated under the microscope. Table 2 provides a list of several algae I found, dominated by green filamentous algae Mougeotia and Microspora, both whose excessive growth is associated with eutrophication. The main diatom, Fragilaria, is found in organically enriched waters and associated with pollution, as is Nitzchia and Gomphonema, also identified in the lake sample I took. The majority of micro-organisms I observed in the algal mat sample are eutrophic and/or pollution-tolerant organisms.

Table 2: Algae Identified in South end of Buckhorn Lake

| Orgnism | Designation | Description & Habitat |

| Mougeotia (filamentous green alga) | Abundant | Cosmopolitan mesophytic algae of enriched environments that tolerates heavy metals |

| Navicula, Cocconeis, Nitchia, Fragilaria, Tabellaria, Gomphonema (diatoms) | Common | Species of several of these diatom genera are commonly found in organically enriched environments, some in polluted water and filter clogging |

| Cosmarium (desmid) | Frequent-Common | Varied environments including clean water |

| Staurastrum (desmid) | Frequent-Common | Common in eutrophic environments |

| Pediastrum (Chrysophyta) | Common | Indicator of eutrophic conditions; taste and odor alga |

| Dinobryon (dinoflagellate) | Frequent | Common in languid pools, especially those rich in organic matter; Indicator of eutrophic conditions; filter-clogging; taste and odor |

| Tiny blue-green filaments (Cyanophyta) | Frequent | Indicator of eutrophic conditions and water pollution |

| Euglena-like Protista | Frequent | Indicator of water pollution |

| Phacus-like (Euglenozoa) | Rare-Frequent | Indicator of water pollution |

| Scenedesmus | Rare-Frequent | Dense in nutrient-rich waters; indicator of change in environment |

| Gastrotrichia | Rare | Meiofaunal free-living invertebrate associated with detritus |

| Nematoda | Rare | Bacterivorous fauna indicative of organic enrichment |

These algal surface mats weren’t forming blooms yet. That phenomenon would occur at the height of late summer, in August and September, when blue greens would dominate to cause surface blooms. Algal blooms, in turn, add organic matter when they die and settle to the soft bottom of the lake, further accelerating the eutrophication process and possibly causing dead zones.

Sources of nutrients come mostly from local runoff (agriculture, storm drains with garden chemicals, pet waste, road salt, leaky septic tanks, and garden fertilizers). With more dense housing (particular close to shore), coupled with shore modification—which often involves removal of natural buffering wetlands (that take up and process nutrients and toxic material)—eutrophication has accelerated since the Ministry of Environment 1976 survey. Much of the shallows of Buckhorn Lake—over 85% of the lake area—are functional wetland.

The controversy over wild rice planting I believe is moot; Buckhorn Lake—and the other Kawartha Lakes of this region—was originally wetland before the dams were built. The lake is naturally shallow (wild rice used to grow abundantly there, I’m told) and currently supports a rich community of submerged and floating weeds such as tape grass, pond lily and others that will continue to accelerate the lake’s advancement toward wetland.

This is where the lake is inclined to go through natural succession.

The algal growth also helps the eutrophication process through active growth, die-off and contribution to sediment buildup. Cottage owners would need to not only use aggressive and costly measures to remove plants (e.g. dredge the lake to increase depth and remove soft organic/nutrient-rich sediments) but they would need to curb abundant algal and weed growth by addressing their own input of sewage (from faulty septic tanks), nutrients and toxins from storm drains and runoff. This is highly unlikely. I know; I’ve worked with several cottage communities gridlocked in this paradoxical scenario. You can’t have it both ways. The density of cottagers has likely doubled since the 1970s when the Ministry of Environment designated this lake eutrophic and identified excessive weed cover at 85% lake cover that included invasive and native aquatic plants. More cottagers means more leaky septic systems, more garden fertilizer runoff, more pet waste and road salt, and more stormwater runoff.

The Kawartha Stewards Association suggest that “no management may be the best option. Depending upon local conditions and regulations, one might extend a dock out into deeper water, or use a swimming platform, thus mostly avoiding the weed beds rather than disturbing them.” They note that marsh communities also protect the shoreline from erosion by slowing wind and wave currents.

A Shoreline Owner’s Guide to Healthy Waterfronts

FOCA have put out an excellent guide for cottagers who live on or near the shore of the lake wishing to be good stewards of the lake-wetland environment. Called “A Shoreline Owner’s Guide to Healthy Waterfronts” this 28-page PDF document provides an excellent summary of a lake, its watershed and how it functions. They provide excellent advice on fish-friendly dock structure, low-impact lakeshore living, controlling invasives and nuisance growths, conservation tips and techniques to prevent and restore shoreline erosion and damage. They include best management practices for lake stewardship that are practical and will make a difference.

In my opinion, the best thing to do is accept the system for what it is: an aging eutrophic system turning into a beautiful and biodiverse marsh that supports a rich wildlife, fish, and bird population. The challenge is to keep it a functioning marsh without blue-green proliferation.

I spotted an osprey and a nest, several great blue herons, loons, mallard ducks, small fish, red-winged blackbirds, and other song birds.

References

Johnson, Frederick M. 1997. “The Landscape Ecology of the Lake Simcoe Basin,” Lake and Reservoir Management 13 (3): 226-239.

Fedaration of Ontario Cottagers’ Associations (FOCA). 2019. “A Shoreline Owner’s Guide to Healthy Waterfronts” (revised edition). 32pp.

KLSA (Kawartha Lake Stewards Association). 2009. “The Root of the Matter…”: Lake Water Quality Report 2008. April. 73pp.

Ontario Ministry of the Environment. 1976. “The Kawartha Lakes Water Management Study—Water Quality Assessment (1972-1976).” November. 141pp.

Todd, Brian J. and C.F. Michael Lewis. 1993. “A Reconnaissance Geophysical Survey of the Kawartha Lakes and Lake Simcoe, Ontario.” Geographie physique et Quaternaire 47 (3): 313-323.

Wehr, John D. and Robert G. Sheath. 2003. “Freshwater Habitats of Algae.” Chapter 2 In: “Freshwater Algae of North America.” Elsevier Science (USA)

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.