When visiting with friends in Mississauga recently I had the opportunity to walk along Etobicoke Creek, a windy creek of ravines and shale banks that flows 61 kilometers south from Oak Ridges Moraine through Caledon, Brampton and Mississauga before emptying into Lake Ontario at the groomed recreation area, Marie Curtis Park. Etobicoke Creek’s watershed is over 200 square kilometers, most of which is urbanized. The TRCA mapped the land cover of the watershed as 67% urban area, 19% rural area, and 14% natural cover.

The riparian park of the creek reminded me of the Don River ravine parks in Toronto and even Central Park in New York. Nestled deep in the urban environment, the park at times offers respite from the sounds, sights and smells of the city—but never completely. There are always signs of the encroaching urban environment.

I’m told that the name ‘Etobicoke’ came from the Mississauga word wadoopikaang, which means “place were the alders grow.” As we walked along the shore of the river, I noted that alders still grow there; some of them were massive tall trees. I later discovered that the towering alders by the mouth of the creek are over 150 years old.

The walk upstream from the creek mouth was pleasant, much of it through riparian mixed deciduous forest of mostly maple, black walnut, basswood, willow, and oak; and, of course, alder. An old stone wall lined one curved section of the creek and main trail. I noted what looked like a stone gate at the bottom of the highest portion and then realized that it was a storm sewer conduit. We passed beneath the GO Train rail bridge, a reminder of the proximity of busy urbanization.

Eventually, we were presented with two paths, the main path through the riparian forest and a path right by the river bank. My friends chose the main path and I chose to walk the shore, where I could investigate life on the shale rocks. There was not much in the way of benthic invertebrates there; a fine layer of silt mixed with some periphyton (attached algae) carpeted the rocks in a gray-green fur.

I stopped by the stream bank where several mature sugar maples rose tall, branches draping over the river to provide some shade. The opposite bank was a steep actively eroding slope of gravel talus. That was all eventually going into the creek, I thought.

Curious squirrels, both red and gray, chittered at me. They had a rich environment to live by: black walnuts, a favourite; and later in the season, acorns from the red oaks, another favourite. Happy squirrels. But the creek, despite some natural beauty provided by the trees and shrubs, is not truly a happy creek. Although people have reported small fish and crayfish in the creek, I saw none. There was no evidence of good aquatic habitat for native crayfish that require silt-free, well-oxygenated water with low nitrite and no toxins. The stream bottom was heavily silted. My sense was that the water quality of Etobicoke Creek was poor. Given that the watershed is 71% urbanized, with fragments of the headwaters in rural environments, it was not surprising to find that the TRCA has consistently given this creek a poor water quality grade since 2013.

Etobicoke Creek Poor Water Quality Grade

Based on several monitoring sites for groundwater, surface water quality, and forest cover, the TRCA Report Card for Etobicoke Creek gives Etobicoke Creek a “D” (poor) grade. The TRCA identified two key watershed issues for Etobicoke Creek:

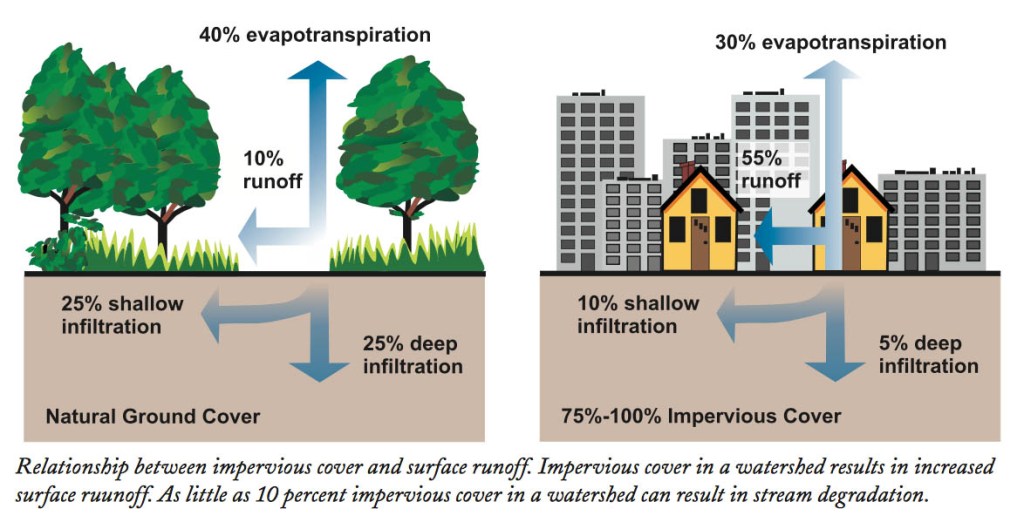

1. Poor Stormwater Management Causes Physical Damage and Chemical Pollution: The creek’s watershed is heavily urbanized and has limited or outdated stormwater management infrastructure; because of this, storm events result in high water flows, erosion and siltation. But the problem isn’t just physical; because of the high proportion of impervious surfaces (e.g. parking lots, rooftops, driveways, and roads), Toronto’s and Mississauga’s urban runoff collects a panoply of contaminants that all run into the stream via storm drains.

The EPA tells us that “because of impervious surfaces like pavement and rooftops, a typical city block generates more than 5 times more runoff than a woodland area of the same size.

Urban runoff typically contains some mean toxic substances that come from various urban activities including traffic, maintenance, construction, and domestic activities. Commercial and light industrial activities add more toxic and persistent chemicals to runoff into the stream.

Many contaminants settle on these impervious surfaces through atmospheric deposition (AD) then wash into the stream in a rain. Chemicals include: endocrine disrupting toxic heavy metals; bacteria; bioactive contaminants (pesticides and pharmaceuticals), personal care products, alkylphenol surfactants, phthalates, nutrients, VOCs, polyethylene, PCBs, perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), microplastics, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). This is just a shortlist:

The USGS recently shared results of an extensive national-scale study (of 21 sites in 17 states) that identified from 18 to 103 organic and inorganic chemicals in a single stormwater sample, which included anything from DEET (insect repellent) and nicotine to wood preservative.

Eleven organic contaminants were pervasive across all stream samples they collected throughout the United States. Urban runoff is dirty stuff. This is what those ‘happy’ squirrels I encountered are drinking.

Virtually all of these chemicals are destructive to hormonal systems. They can stunt growth, lower immunity to diseases, cause infertility and sex reversal; they can cause autism, mutations, miscarriage, birth defects, kidney and liver damage. Several, like PFOS, are very persistent and therefore called “forever chemicals.” They cause cancer. Many of these persistent chemicals do not need to be in large quantities to harm or kill life.

2. Effect of Urban Heat Island and Channel Manipulation: surfaces of high urbanization (creating impermeable surfaces, removal of natural vegetation and trees) typically absorb more heat in the day, creating what is called an Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect. Less natural vegetation and lack of shading trees in a creek’s watershed also contributes to the creek’s: flash flooding due to less water retention; aquatic contamination from lawn herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers; and the creek’s increased temperature (impacting fish and benthos). All three together cause interminable stress to any potential aquatic life and other life that might use the creek. Many urban creeks, such as Etobicoke Creek, flow partially in the dark through pipes or straightened and constricted in concrete channels, hampering their ability to function. Straightening of the stream, combined with less functional riparian areas, also exacerbate flash flood events, which, in turn, accelerate the destruction process of the aquatic ecosystem posed by contaminants.

Details of TRCA Report Card

Surface Water Grade: ‘D’. Based on phosphorus and E. coli bacteria measurements at three stations and benthic invertebrate assessments at thirteen stations, Etobicoke Creek watershed received a ‘D’ grade for surface water quality. The grade might have been lower, given that chloride concentrations (a known issue for this watershed) was not considered in the grading. Chloride pollution in a watercourse results typically from road salt; elevated chloride harms aquatic life.

Forest Conditions (Including Streamside Cover) Grade: ‘D’. The watershed consists of 5% forest cover with <1% interior forest cover and 22% streamside cover. While streamside cover has increased by 4% since the last report card in 2013, this improvement seems minimal considering the importance of a healthy riparian zone for stream health.

A riparian area is essentially a strip of moisture-loving vegetation growing along the edge of a natural water body. Riparian cover should ideally be closer to 100% to achieve the important functions. Functions that include:

- shading to reduce stream temperature and wind protection

- consolidation of banks and slopes to prevent erosion and siltation;

- storing of water during rain events and releasing it to the stream during low flow periods; absorption and dissipation of water energy during floods and other storm events;

- filtering out contaminants through incorporation

- food sources and habitat for emerging aquatic insects and shelter for fish (via overhanging banks, etc.)

Given that much of what impacts the health of the creek comes from urban activities, healthy riparian vegetation with sufficient cover plays a key role in reducing pollution to the creek from urban runoff and allowing the creek to manage itself. The bottom line is that these riparian areas need to be sufficiently large and healthy to do their job of help keep the stream healthy. These riparian areas—if sufficiently large—can clean the air, buffer noise, create a cooler microclimate, take in carbon (helping against global warming) and provide aesthetic and wellness value.

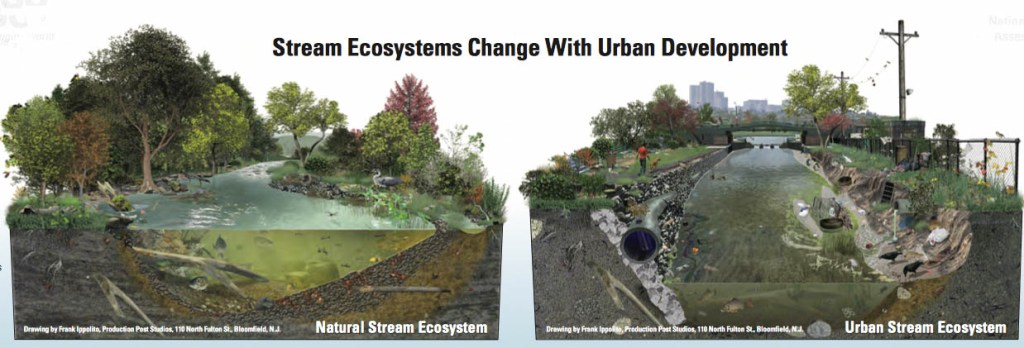

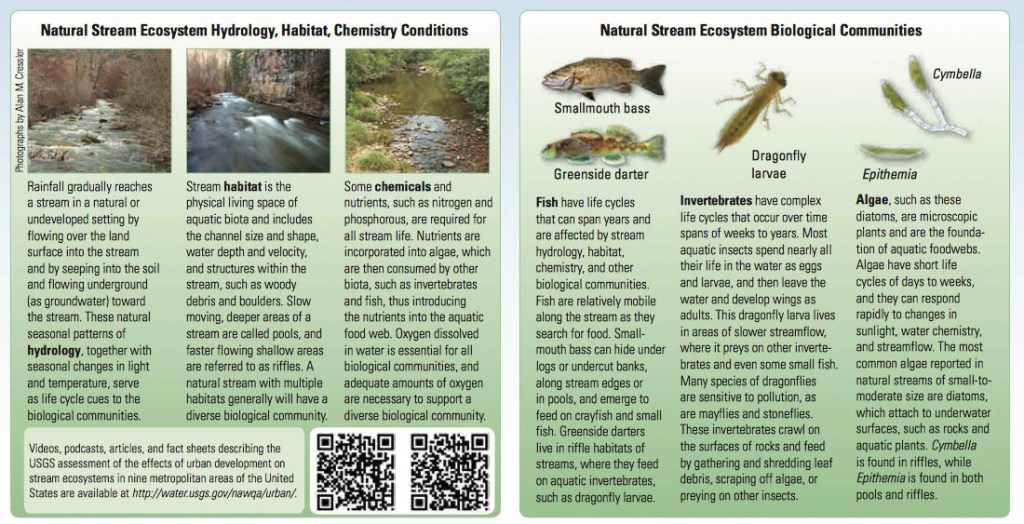

Stream Ecosystem Change with Urban Development

Stream ecosystems are defined by the hydrology, habitat, and chemistry conditions and the biological communities in the stream—all influenced by the activities in the surrounding watershed. The USGS tells us that a complex and well-balanced natural stream ecosystem is well adapted to seasonal environmental changes, such as annual flooding and drought cycles. Urbanization by degrees alters the hydrology, habitat and chemistry of a stream that stresses the biota living in it and near it. Tree removal warms up streams, stressing the biota. Increased impervious surfaces that accumulate and deliver pollution from urban activities during flash floods in rain events, erode streambanks and scour stream bottoms, and degrade fish spawning and feeding habitats. Over time, the stream changes from a biodiverse healthy ecosystem into a stressed system where only pollution-tolerant, low oxygen-tolerant, and warm-tolerant species can survive.

Importance of Healthy Riparian Habitat

Tucanada.org describes the consequence of poor management of a riparian area, which relates to Etobicoke Creek:

During a flood or other high water occurrence damage to the riparian or shoreline area may occur resulting in the removal of vegetation or sections of the bank. After the event, the riparian area begins to heal naturally. Over time vegetation, such as willow shoots, sprout up through deposited gravels and mud reinforcing the bank once again. Human intervention to repair the damaged shores and banks of riparian areas frequently involves “quick fix” solutions by replacing the lost vegetation with rip rap. Rip rap, loose stones and rocks used to form a foundation for a shoreline or breakwater structure, alters the riparian area, preventing the natural re-growth of vegetation. Bank armoring using rip rap may also impede the flow of groundwater into the stream and deflects water energy to less protected areas resulting in addition damage. This practice is particularly harmful to smaller streams where groundwater is a major source of stream flow that maintains water levels and adequate temperature to support aquatic life.

TUC adds that bio-engineering techniques, while they may be more labor-intensive, often take significantly less time to install and are less costly AND allow natural growth to develop and restore disturbed banks and shores. They suggest wattle fencing and live staking using willows and poplars within a riparian area to preserve the connection between the upland area, stream channel and the shore.

What the City Should Be Doing

Masoner et al. reported in the 2019 issue of Environmental Science & Technology that, “municipalities and water-management agencies worldwide are increasingly using stormwater control measures (SCMs) at various scales to minimize contaminant transport to receiving waterbodies, reduce stormwater volumes, collect stormwater for reuse, and increase groundwater recharge.” According to Masoner et al. “SCMs can be an effective approach for reducing concentrations of select contaminants, including total suspended solids, nutrients, copper, and zinc,” all contaminants that exist in Etobicoke Creek. SCMs include the creation (or re-enstatement) of stormwater-retention wetlands/ponds/lakes that provide aquatic habitats and functional filtration/retention areas. The irony to this for Etobicoke Creek is that this would involve putting back what was once taken away.

What the City Is Doing

Alfred Kuehne Naturalization Project: a 400 stretch of straightened concrete channel was removed and naturalized, creating riffles and pools. Riparian vegetation was planted on the creek shores and the floodplain was reconnected with the stream to provide flood relief and create wetland habitat.

County Court SNAP Implementation in Brampton: Several homeowners have undertaken various home retrofit initiatives which include landscaping, tree planting, and energy and water efficiency measures. The City of Brampton constructed a bio-filter swale to capture and treat local stormwater runoff in the neighbourhood.

A Green Home Makeover serves as a demonstration site for water efficient landscaping and rainwater management practices, as well as building energy and water efficiency retrofits.

What We Can Do

According to Müller et. al. residential lawns and turf areas (e.g. sports fields, golf courses and groomed parks) are ‘hotspots’ of nutrient input into stormwater: “Lawns and their soils are among the most important sources of total and dissolved phosphorus in urban runoff.” When nutrients enter the stream, they trigger algal growth, which, if over-extensive, can choke a creek and kill fish and other aquatic life.

Some of the best things we can do are simple but effective:

- Plant native trees and shrubs on your property

- Reduce or eliminate the use of deicing salt, pesticides, and fertilizers on your property

- Volunteer for community tree plantings, litter pick-ups, or other stewardship events

References:

Masoner, Jason R. et al. 2019. “Urban Stormwater: An Overlooked Pathway of Extensive Mixed Contaminants to Surface and Groundwaters in the United States.” Environ. Sci. Technol. 53(17): 10070-10081.

Müller et. al. 2020. “The pollution conveyed by urban runoff: A review of sources.” Science of the Total Environment 709. USGS. 2021. “Ongoing Research to Characterize the Complexity of Chemical Mixtures in Water

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.