Every summer I travel back to the Vancouver area in British Columbia to visit friends and family. I’m also there to see my old friends, the big trees, and meet new ones on some new adventure.

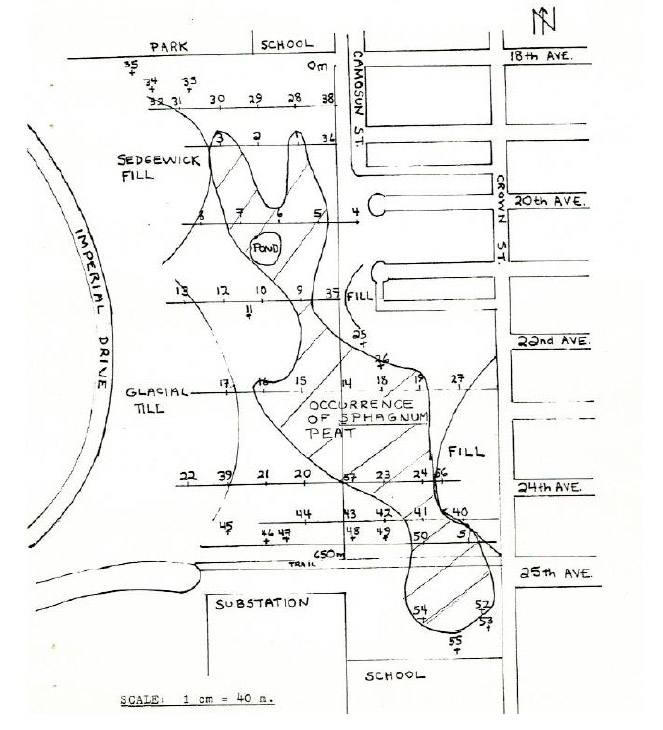

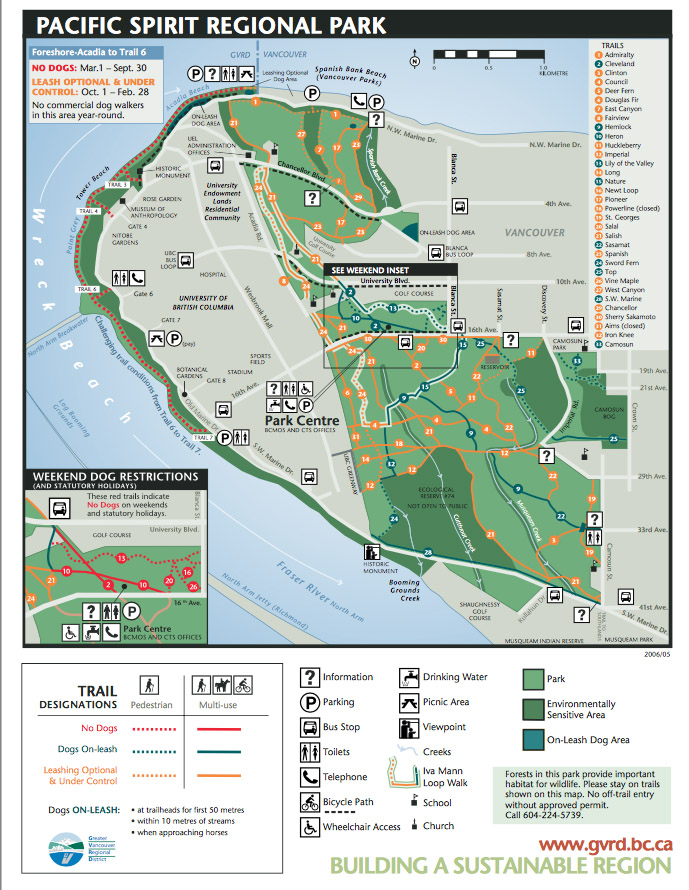

Camosun Bog, located on the eastern-most end of Pacific Spirit Regional Park (on the unceded territory of the Musqueam Nation) is an old friend for me in several ways. I took my limnology students there a life time ago as part of a section on bogs and other wetlands, during my years teaching at the University of Victoria. Camosun Bog is also the oldest bog in the Lower Mainland. It was created shortly after the last ice age 10,000 years ago.

.

.

How Camosun Bog Formed

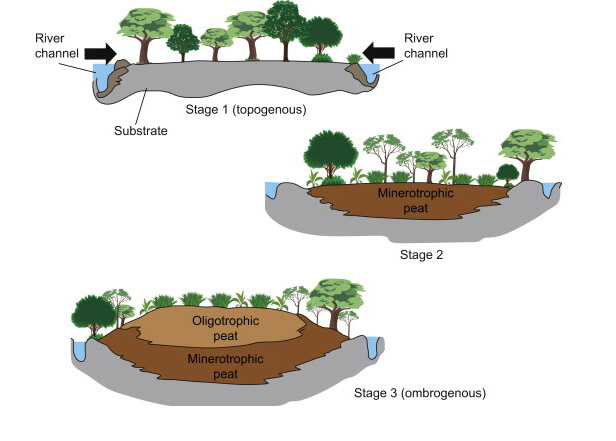

When the Vashon glacier retreated 12,500 years ago, it left a depression that developed into a prehistoric lake that slowly filled in with plant debris over thousands of years. Peat-forming Sphagnum mosses along the edges of the lake likely helped escalate the lake infilling with plant debris (called terrestrialization) along with an outward accumulation of organic matter at the shorelines (called paludification).

.

.

Initial root masses of bog peat likely developed over the lacustrine mineral deposits as the transition from sedge-dominated marsh to limnogenous fen took place. The plants eventually choked out the inflows, depleting the oxygen and nutrients the inflows carried. Soil conditions became increasingly acidic from the production of humic acid during decomposition of plant debris and from active cation exchange by Sphagnum mosses.

With anoxia and increased acidification (low pH of 4 or less), the rate of decay was reduced (think of Tollund Man); this impeded the drainage of the lake and led to water-logged soil conditions.

.

.

These conditions discouraged the growth of vascular plants but were perfect for Sphagnum moss, which took over. Peat accumulated as minerotrophic peat, at first as water passed over or through mineral parent materials. As the peat layer grew higher, the vegetation became progressively more isolated from the mineral-soil-influenced groundwater and received water only through precipitation (ombrotrophic peat). As bog succession continued, the perched water table in the peat became isolated from the water table of the local terrain, and the bog was unaffected by runoff or groundwater from the surrounding mineral soil. The sponge-like acidic properties of Sphagnum maintained this true bog’s climax community for thousands of years.

.

It felt almost otherworldly visiting the bog this time, and as I saw familiar bog friends thriving amid a carpet of Sphagnum and haircap moss—such as sundew, Labrador tea, bog laurel, cloudberry, and bog cranberry—my face creased in a beaming smile. It was nice to see that this bog was doing alright. It wasn’t always this way…

.

History of Camosun Bog

This unique bog ecosystem was nearly destroyed in the early 20th century through infill and draining. The land was used as a dumping ground for sawdust and other waste materials and the city encroached. In 1919, a fire led to the establishment of shore pine and western hemlock trees, which shifted the bog ecosystem towards a forest community dominated by western hemlock. By the 1970s, the Greater Vancouver Regional District Parks (GVRD) recognized the ecological significance of the bog and began restoration work with help from the UBC Technical Committee and the Vancouver Natural History Society. In 1971 the bog was designated a park and off-limits to development. The district built experimental water retention structures and constructed boardwalks to prevent damage to the fragile ecosystem through trampling. 150 hemlock trees were removed and attempts made to restore the lost Sphagnum amid invasion of birch, salal, salmonberry, blackberry, and sword fern. In 1996, the Camosun Bog Restoration Group, affectionately known as the “crazy boggers,” helped restore the bog by clearing and planting sphagnum plugs in the damaged peat. As the Sphagnum took hold, other bog-specific plants such as sundews, bog cranberry and shore pines re-established.

.

However, none of these efforts will succeed without restoration of the original hydrology of the bog, which has been altered through draining and filling, sewers, and storm water management—a larger challenge, considering the surrounding development. Nutrient enrichment from alterations in drainage are also impacting the bog community, favouring non-bog plant species. There’s still work to be done here.

.

Walking Through Camosun Bog

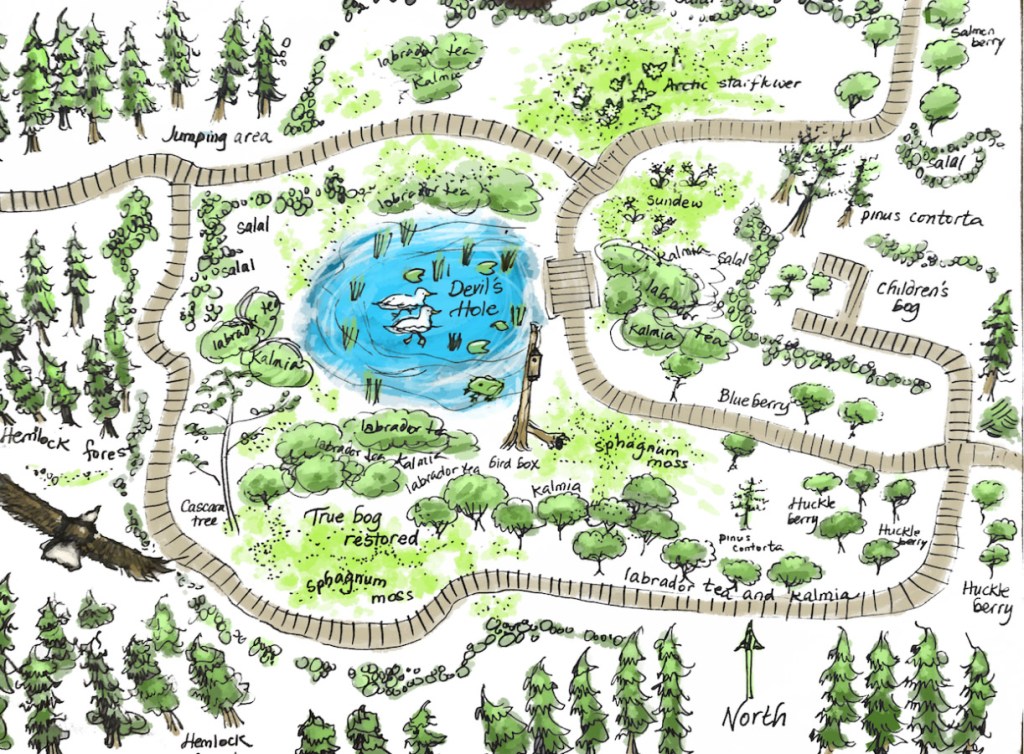

Anne and I parked our vehicle on Camosun Street, just past 19th Avenue, and walked into the bog past the marked entrance sign. We were immediately walking along a winding 300-m boardwalk that encircled and bisected the bog. Informative interpretive signs pointed out each of the bog’s iconic bog communities with information on their adaptation to this unique environment.

.

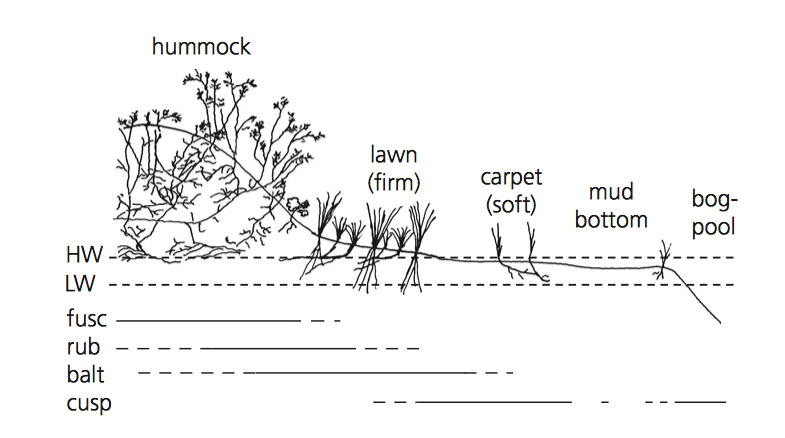

We wandered through various bog micro-habitats that included hummocks with dwarf shrubs, lawns with cyperaceous plants, bryophytes and grasses, bryophyte-dominated carpets, and mud-bottoms of bare peat with a thin cover of algae and establishing moss. At the very centre, I noticed what might become a small open pool during the rainy season.

.

.

Other than the odd bird call, we saw no other signs of wildlife. The bog is, however, a rich repository for wildlife. Birdlife includes raptors (hawks, eagles, vultures, and owls) and Great Blue Heron, the Rufous Hummingbird, Belted Kingfisher, Red-breasted Sapsucker, Downy and Pileated Woodpecker, Raven, and numerous songbirds (e.g. Warbling Vireo, Chestnut-backed Chickadee, Red-breasted Nuthatch, Song Sparrow, Brown Creeper, Yellow Warbler, and my personal favourite—Swainson’s Thrush). On several recent visits in late July, I was continually serenaded with the cat-like call of a Spotted Towhee (Pipilo maculatus).

.

.

Small wildlife such as rabbits, squirrels, voles, mice and chipmunks, of course thrive there. I’m also told that coyotes and racoons are in the area—both are urban dwellers. Of course, what we don’t see unless we look very closely and with a microscope, is the rich microscopic plant and animal life that lives in the Sphagnum moss habitat. Hundreds of microscopic species of desmids, diatoms, algae, cyanobacteria, amoebae, rhizopods, flagellates, ciliates, rotifers, worms, nematodes and more live in the aquatic micro-habitat provided by the mosses of Camosun Bog. Small to tiny animal life such as frogs, water beetles, dragonflies, caddis flies and midges also thrive in the bog.

.

.

The western end of the bog boardwalk led into the forest proper, mostly Western Hemlock, large cedars, Douglas fir and spruce, interspersed with bigleaf and vine maples. We climbed up a tall stairway to Camosun Trail that led south through mixed forest, past a BC Hydro Substation, and eventually to Top Trail, where we walked east along a gravel path beneath a tall archway of poplars and maple trees that skirted past a residential section. We completed a loop that took us onto Crown St. to West 21st and eventually to where we had entered the bog on Camosun St.

.

.

.

.

Camosun Bog’s Unique Ecosystem

While bogs may range greatly depending on several factors, all bogs have several things in common as wetlands. These include:

- The bog contains a high water table

- The bog is strongly acidic (often pH of less than 4) and often anoxic

- The bog is nutrient-poor (oligotrophic or dystrophic)

- Sphagnum is present and peat is present, usually thicker than 30 cm

- The bog receives most of its water and nutrients from precipitation (ombrotrophic) as opposed to from surface or groundwater input (minerotrophic)

.

.

Role of Sphagnum in Maintaining a Bog Environment

Camosun Bog is dominated by the actions of Sphagnum, which is known as the ‘bog builder’ because it holds water, lowers oxygen levels and secretes acid, keeping conditions suitable for peat formation and specialist plants. Sphagnum acts like a giant sponge, absorbing rainfall and releasing it slowly; it can absorb up to 20 times its own weight in water, holding it in specialized empty cells. Sphagnum actively maintains a pH of 3.0 to 4.5 by creating cation exchange sites (uronic acid polymers) loaded with H+. The dry mass of Sphagnum contains from 10% to 30% uronic acid. The uronic acid polymers take up base cations, mostly ions such as calcium and magnesium, and in exchange releases hydrogen ions (acid ions).

.

.

Who Lives in Camosun Bog?

Because of its unique environment, many bog inhabitants such as plants, animals, fungi and lichen have highly specialized adaptations to poor nutrients, and waterlogging. Bogs typically support Sphagnum and ericaceous shrubs such as bog myrtle (Myrica gale), which has fungal-infested root nodules for nitrogen fixation. Sedges are common as are carnivorous plants, such as the sundew that get its nutrients by trapping insects.

.

Sphagnum spp.

Sphagnum: Sphagnum is the foundation of the bog’s unique environment and specialized community. According to Richard S. Clymo of Queen Mary and Westfield College in the UK, Sphagnum is “far and away the most successful bryophyte and, by the criterion of the amount of carbon incorporated, is possibly the most successful plant genus of any kind.” This is because it thrives (not just tolerates) water with unusually low dissolved solids, makes the water around it very acidic, and decays very slowly.

.

A collection of thirteen species of Sphagnum moss and other mosses carpet Camosun Bog’s surface with soft red-green-yellow. All Sphagnum have hollow stems and capillary films between overlapping leaves that hold large amounts of water, helping to keep the water table close to the surface. Sphagnum does not rot easily (partly by maintaining an acidic pH) and the living parts of the plant are attached to the dead plants (peat) below the surface, forming a large ‘sponge.’ Peat has accumulated over hundreds of years, building the soil of the bog as deep as 5 m in some sections. Sphagnum is responsible for creating the iconic acidic, low nutrient and water-logged growing conditions of Camosun Bog that attracts its specialized community. Sphagnum has been and continues to be well-used by indigenous peoples for its rich medicinal qualities, as a water absorbent, and for its acidic and antiseptic properties.

.

Bank Haircap Moss

.

Bank Haircap Moss (Polytrichum formosum): This moss typically prefers shaded, poor soils and humus in damp coniferous forests and cool temperate rainforests. This moss is often found with Sphagnum in wetlands. Given the encroaching hemlock forest, it is likely that suggestions by several bog scientists that Bank Haircap moss is outcompeting the Sphagnum should be taken seriously.

.

Broom Forkmoss

.

The Broom Forkmoss (Dicranum scoparium): I found this delicate hair-like moss in round patches throughout the edges of the bog where this non-bog moss prefers dry to moist forested areas, often on rotten wood or bases of trees.

.

Splendid Feather Moss

.

Splendid Feather Moss (Hylocomium splendens): I also found this perennial clonal moss on the northwest corner of the bog, close to the hemlock forest. It is often found colonizing ledges, humus (where I found it), and decaying wood in moist cool deeply shaded woodlands and ravines. The splendid feather moss is also known as stair-step moss and mountain fern moss–which it resembles.

.

Curved Silk Moss

.

Curved Silk Moss (Plagiothecium curvifolium): This cosmopolitan moss typically grows in shaded, damp woody environments, especially in coniferous forests. It prefers acidic substrates like tree bases (where I found it), fallen logs. tree stumps, and acidic soils with humus and decaying litter. It is a calcifuge, meaning it avoids calcium-rich (alkaline) conditions and is commonly found on trees with acidic bark, such as pine, birch, and hemlock.

.

Roundleaf Sundew

.

The Roundleaf Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia): This carnivorous plant, found in most parts of Canada, is specialized to grow in bogs, marshes and fens by feeding on insects for the nutrients otherwise lacking in its environment. This species of sundew has small, nodding 5-petaled pinkish flowers and hair-covered leaves arranged in a rosette. The red glandular hairs (trichomes) exude a sticky mucilage to attract and entrap insects and other prey. Sundew (Drosera spp.) thrives in wet stands of black spruce, Sphagnum bogs, silty and boggy shorelines, and wet sands. Sundew prefers open, sunny or partly sunny habitats. Carnivory gives the sundew nutrients, particularly nitrogen, which is often lacking in the bog environment. Because it contains flavonoids, this cool looking diminutive plant has some awesome medicinal properties such as anti-inflammatory and antispasmotic properties.

.

.

Labrador Tea

.

Labrador Tea (Ledum groenlandicum): This member of the Ericaceae typically inhabits the moist acidic habitats of bogs, swamps and wet conifer forests. They are easily identified by their leathery leaves and looking at the underside of their leaves which are brown and hairy. They spread easily through rhizomes and prefer full sunlight, consistent moisture and acidic nutrient-poor organic soil. Despite containing toxic alkaloids poisonous to livestock (and humans in concentrated doses), the leaves are used to make beverages and medicines—most commonly a fragrant tea. The Teetł’it Gwich’in of Fort McPherson drink Muskeg tea (lidii masgit) from leaves and flowers as a relaxant and for its high Vitamin C.

.

.

Bog Laurel

.

Bog Laurel (Kalmia polifolia): This ericaceous perennial evergreen shrub thrives in cold acidic bogs. The bog laurel can act as a medicine or poison. Its foliage and nectar-filled flowers contain toxic resins called grayanotoxins. One site claims that the honey made by bees that pollinate this plant is also poisonous. Leaves are shiny dark green, slightly curled over with light green undersides.

.

Bog laurel is often confused with Labrador tea in that they do resemble one another and live in the same habitat. The main difference can be seen in the leaves, both upper side and underside: the upper side of the Bog laurel is shiny while it is slightly buffed in the Labrador tea; their undersides are distinctively different with Bog laurel being lighter in colour but fairly smooth and Labrador tea very hairy or ‘furry’, starting white in young leaves and growing golden brown in older leaves.

.

Bog Cranberry

.

Bog Cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos): This flowering rhizomous plant in the heath family is widespread throughout the cool temperate northern hemisphere. The leaves are leathery and lance-shaped with red berries. This plant typically grows in bogs and acidic moist to wet soils, low in nitrogen with a high water table. It also lives in coniferous swamps. It is often found growing on hummocks of Sphagnum. Its berries are edible and are used as both medicine and food.

.

Lichens

.

I identified four interesting lichens (so far!) in Camosun Bog, all found in the southwest side of the bog.

Fairy Puke Lichen

.

The Fairy Puke Lichen (Icmadophila ericetorum): I discovered this lichen in the area now covered in mounds and hillocks of Sphagnum and other mosses, growing on rotting logs and stumps is a ‘dusty’ blue-green lichen with pink ‘disks’, which are the fungal fruiting bodies (apothecia) of this lichen. This lichen is also called Candy Lichen, but I think the former common name is more imaginative.

.

British Soldier & Lipstick Powderhorn Lichen

.

British Soldier Lichen (Cladonia cristatella) & Lipstick Powderhorn Lichen (Cladonia macilenta): Throughout the bog I also found these colourful lichens growing on the peat surface, rotting logs and stumps and the trunks of hemlocks. These lichens typically lacks cups and prefers open or well-lit wooded areas and heathlands growing on strongly acidic wood and soil.

Common Powderhorn Lichen

Common Powderhorn Lichen (Cladonia coniocraea): This rather common lichen is rather ubiquitous, living in all sorts of places, including rotting wood the forest floor, fence posts, and the bases of trees. It seems to particularly like pine, spruce, and birch. It thrives in shaded, damp, and decaying organic matter, but can also be found in northern prairies, urban areas, and on weathered wood due to its resilience. See the image above, under “Lichens.”

Ladder Lichen

.

Ladder Lichen (Cladonia cervicornis ssp verticillata): this strangely alien-looking squamulose lichen with frilly fruiting bodies shaped somewhat like golf tees or trumpets (podetia) has fairly smooth splash cups out of which grow more podetia; splash cups are bordered by bright ruddy brown spore-bearing apothecia which contain pycnidia that release asexual fungal spores called conidia.

.

Canadian Bunchberry

.

Bunchberry (Cornus canadensis) or Creeping Dogwood can be found mostly on the edges of the bog as ground cover under Labrador tea, in with Sphagnum and Polytrichum moss. I found it mostly near the entrance to the bog, along with a mix of other non-bog plants such as Salal, Hardhack, and Deer Fern. Canadian Bunchberry is not a true bog plant in that, while it likes peaty soils, it is not restricted to bog environments; it is most often found in cool, moist mixed and coniferous woods, thickets and damp clearings. This includes sugar maple-red maple stands or sugar maple and yellow birch stands.

.

.

White Beak-Sedge

.

White Beak-Sedge (Rhyncospora alba) is a tufted herbaceous perennial that favours wet, acidic and nutrient poor soils, thriving in Sphagnum-dominated bogs and peaty grasslands. It is ofen used as a positive indicator for bog and mire ecosystem health.

For a complete list of plants, lichens, fungi, birds and other wildlife that frequent or grow in the bog, check the Camosun Bog Restoration Group site.

.

.

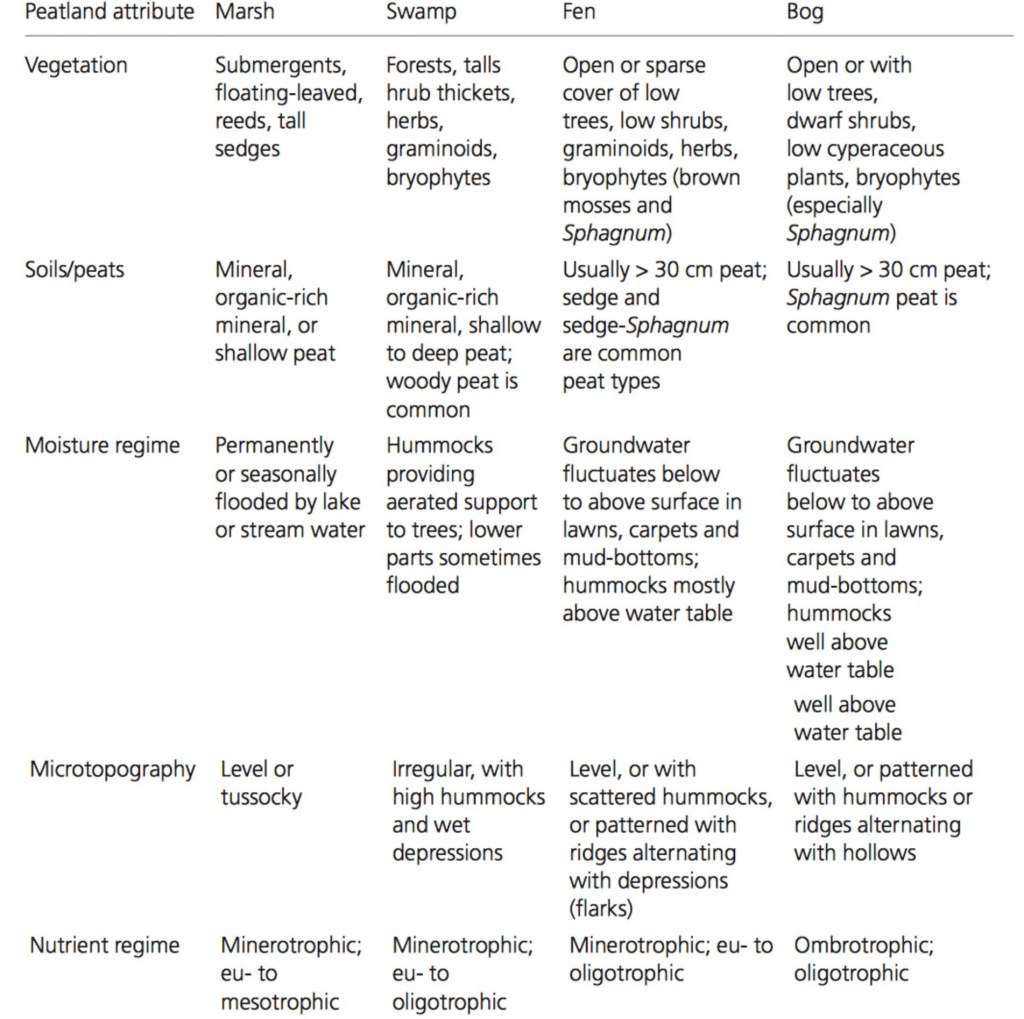

Peatland Habitats & Characteristics

.

.

Dictionary of Terms:

Bog: Organic wetland/peatland. In North America, a bog may be defined as a Sphagnum-dominated peatland; European usage based on the work of Sjörs and Heinselman defines a bog as an Ombrotrophic peatland, nourished by precipitation (and airborne dust). The bog’s surface is above the surrounding terrain or otherwise isolated from laterally moving mineral-rich soil waters. Peat is generally more than 30 cm deep, extremely nutrient-poor and strongly acidic with surface water pH usually around 4 or lower.

Marsh: characterized by standing or slowly-moving water with submergent, floating-leaved, or emergent plant cover. Marshes are permanently or seasonally flooded, with nutrient-rich water generally remaining within the rooting zone for most of the growing season. Bottom surfaces may be mineral glacial drift, aquatic sedimentary deposits, or precipitates of organic or inorganic compounds.

Mire: wet terrain (a wetland) dominated by living peat-forming plants (Sjörs, 1948). Mire differs from a peatland due to the accumulation depth of peat. The term mire may also encompass fens and bogs, depending on the jurisdiction defining it.

Fen: a minerotrophic mire, nourished by mineral soil groundwater, with higher pH than bogs and usually more nutrients.

Peatland: Peat forming ecosystem, either a fen or bog. Marshes are not peatlands, given they are open systems that do not have the requisite conditions for forming peat (e.g. low oxygen and low decomposition, low nutrients and often lack of inflow)

Wetland: Land that is saturated with water long enough to promote wetland or aquatic processes as indicated by poorly drained soils, hydrophytic vegetation and various kinds of biological activity which are adapted to a wet environment, consisting of either a marsh, swamp, fen, or bog (National Wetlands Working Group, 1988, 1997). Organic wetlands contain more than 40 cm of peat; mineral wetlands have little or no peat.

.

.

.

References:

Clymo, Richard S. 1997. “The Roles of Sphagnum in Peatlands.” Chapter 10, pp. 95-99, In: “Conserving Peatlands” edited by L. Parkyn, R.E. Stoneman

Heinselman, M.L. 1963. “Forest sites, bog processes, and peatland types in the glaxial lake Agassiz Region, Minnesota.” Ecological Monographs 33: 327-374.

Hemond, H. F. 1980. “Biogeochemistry of Thoreau’s Bog, Concord, Massachusetts.” Ecological Monographs 50: 507-526.

Irish Peatland Conservation Council. “Sphagnum Moss—the Bog Builder”.

Kiss, G. K. 1961. “Pollen analysis of a post glacial peat deposit in Vancouver. B.S.F. Thesis, University of British Columbia.

Klinger, L. 1996. “The Myth of the Classic Hydrosere Model of Bog Succession.” Arctic and Alpine Research 28: 1-9.

Le, Andrea. 2020. “Groundwater Elevation and Chemistry of Camosun Bog, British Columbia, and Implications for Bog Restoration.” In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science. Simon Fraser University. 64 pp.

Paper, D.H.; Karall, E.; Kremser, M.; Krenn, L. (April 2005). “Comparison of the antiinflammatory effects of Drosera rotundifolia and Drosera madagascariensis in the HET-CAM assay”. Phytotherapy Research. 19 (4): 323–6.

Pearson, A. 1983. “Peat Stratigraphy, Palynology and Plant Succession in Camosun Bog.” B.Sc. Thesis, University of British Columbia.

Pearson, Audrey F. 1985. “Ecology of Camosun Bog and Recommendations for Restoration.” Burnaby, B.C., Greater Vancouver Regional District Parks Dept.

British Columbia Soceity of Landscape Architects. 2022. “Re-conceptualization & Repair: Camosun bog and the manipulation of natural systems.” BCSIA.org.

Quinty, F. and L. Rochefort. 2003. “Peatland Restoration Guide” 2nd Edition. Canadian Sphagnum Peat Moss Association and New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources of Energy.

Rydin, Håkan & John K. Jeglum. 2013. “Peatland Habitats,” Chapter 1, In: “The Biology of Peatlands”, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press.

Sjörs, H. 1948. “Mire vegetation in Bergslagen, Sweden.” Acta Phytogeographica Suecica 21: 291pp

Watmough, D. and A. Pearson, 1990. “Camosun Bog Summary Report.”

Zoltai, S.C. and D.H. Vitt. 1995. “Canadian wetlands: Environmental gradients and classification.” Vegetatio 118: 131-137.

.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

5 thoughts on “The Wonders of Camosun Bog, Vancouver”