Those who are inspired by a model other than Nature, a mistress above all masters, are labouring in vain—Leonardo daVinci

I write science fiction. The alien race in my 2005 science fiction book Collision with Paradise live 100% sustainably in a cooperative and synergistic partnership with their environment. This includes the use of intelligent organic houses with self-cleaning floors and walls, heated, fueled and lit by organisms in a commensal relationship. Everything works on a natural cycle of harmonious renewal and natural evolution.

Science fiction? Think again. Science fiction is turning into fact.

“In the future, the houses we live in and the offices we work in will be designed to function like living organisms, specifically adapted to place and able to draw all their requirements for energy and water from the surrounding sun, wind and rain. The architecture of the future will draw inspiration, not from the machines of the 20th century, but from the beautiful flowers that grow in the landscape that surrounds them.”

Bob Berkebile and Jason McLennan, Architects

Humans have been getting ideas from other animals and plants since long before Leonardo DaVinci’s quote at the top of this article. Application of these ideas has been haphazard, and not particularly aimed at green design. Janine Benyus, leading proponent of nature-based design, first proposed in her book “Biomimicry” that learning from nature would be the perfect tool for eco-design. Engineering inspired by nature can be “functionally indistinguishable from the elegant designs we see in the natural world,” says Benyus, who founded the Biomimicry Institute to research and educate the world on sustainable biomimetic design.

Examples of Biomimicry and Biomimetic Design

…Glass that “breathes” like gills. Solar cells that imitate photosynthesizing leaves. Ceramics with the tough strength of abalone shells. Self-assembling computer chips that form in ways similar to how tooth enamel grows, adhesives that mimic the glue that mussels use to anchor themselves in place, and self-cleaning plastics based on a lotus leaf.

Biomimicry is already being applied in large-scale challenges. Kyosemi, a Kyoto-based company, developed a power-harvesting solar cell that imitates the way trees collect sunlight. Called Sphelar, the product is made up of little spherical cells that can be incorporated into a building’s windows. Unlike standard photovoltaic panels, Sphelar absorbs light from many directions, providing more consistent power generation as the sun moves across the sky. Similarly, Osaka University used the example of the forest canopy to cool buildings (e.g., the Frontier Research Center).

Kinetic Glass was developed by Soo-in Yang and David Benjamin as a responsive surface that reacts to environmental conditions and changes shape via curling or opening and closing ‘gills.’ Kinetic glass is based on animal respiratory systems and made with a slit silicone surface that lets air pass through. Its tiny sensors detect levels of certain gases and opens or closes its “gills” accordingly.

Scientists are taking their cue from the air-purifying ability of plants and fungi to create barriers that not only reduce noise but remove harmful substances. Imagine, for instance, concrete that absorbs carbon dioxide, highway barriers that break down smog, and paint that eliminates odors in the room. Architects Douglas Hecker and Martha Skinner of the design studio Fieldoffice created the SuperAbsorber highway barrier that reduces local airborne pollution through a process known as photocatalyzation. Italcementi, an Italian maker of photo-catalytic cement, claims that the airborne pollution of a large city could be cut in half if pollution-reducing cement were to cover just 15 percent of urban surfaces.

The spiky exterior of the Singapore Arts Centre, located near the equator and subject to a hot and humid climate all year round, is inspired by polar bears. The nearly transparent bristles of the polar bear reflect as much or as little sunlight and heat as necessary (based on whether they lie flat or raised) for the bear to maintain an optimal temperature. The arts centre uses the same principle, using aluminum panels and light sensors.

Another easy example of biomimicry is the use of the bee’s honeycomb shape, the interlocking hexagonal shapes that carry a number of material advantages in engineering and construction. Not only does this geometrical shape use less material, honeycombs also allow more heat to dissipate for cooling, and they are strong, lightweight, and crash resistant.

Building skins (envelopes that cover exterior walls, roove and any openings to the outside world) will help control heat, energy, sunlight, plumbing and other environmental factors—preferably without the use of electricity.

Use of Symbiosis in Ecosystem Design

There are two things missing in this scenario of “sustainable architecture” and design. In their absence, the longevity of our continued existence will be threatened and the success of green design will falter. One is the concept of synergy and the other is the role humanity—particularly our communities—will play in this partnership.

In my book, Collision with Paradise, the alien race discovered by my hero had formed a true synergistic relationship with nature. They had not just copied some of nature’s tricks or mimicked her cool attributes. They had formed a natural and respectful synergistic partnership with Nature. This is not the same as using Nature’s tools, per se, to improve on old designs.

Because, in truth, it is not so much tools like biomimicry that is required; what is needed is a true paradigm shift in how we relate to our environments, from our bedrooms to our communities. I am referring to “symbiotic design”, a living design that incorporates all aspects of a community.

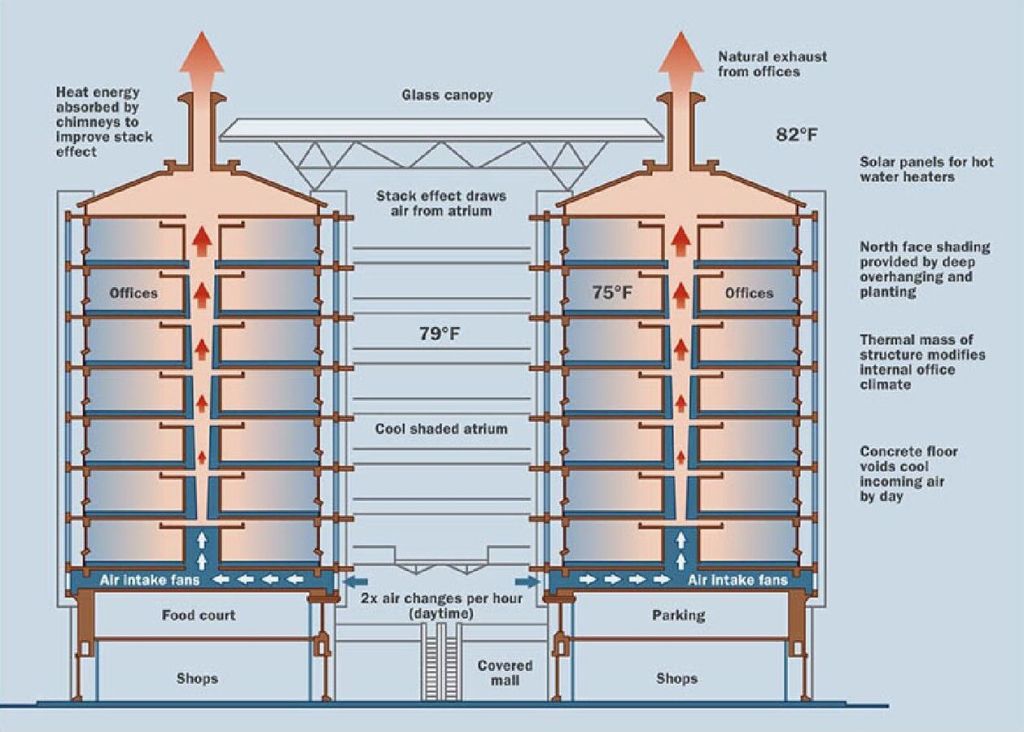

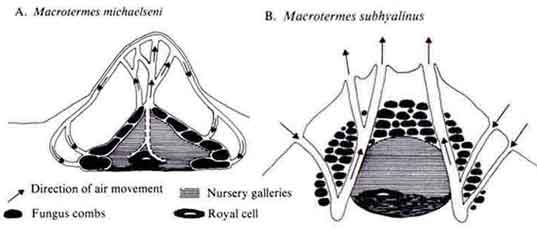

Researchers at the University of Melbourne, John R.J. French and Berhan M. Ahmed, respectfully touch upon this concept when they discuss a human-termite design partnership. They explore the termite model, which meets all nutrition, energy, waste, disposal needs, shelter, and food sources in a true symbiotic relationship; and they are applying it to how we design our buildings. The Eastgate Centre Building in Harare Zimbabwe, already mimics the way tower-building termites construct their mounds to maintain a constant temperature.

Engineers copied the way the insects constantly open and close vents in the mound to manage convection currents of air and the building consumes less than 10% of the energy used in a similar sized conventional building. “We need to emulate the symbiotic abilities of termites to survive over time, for we all live on this symbiotic planet, and symbiosis is natural and common,” French and Ahmed remind us.

Embracing Ecosystem Design in Sustainable Architecture

The term “sustainable architecture” describes environmentally-conscious architectural design, framed by the larger concept of environmental and economic responsibility. This implies responsible leadership and strong partnership with community tied to respect for Nature. Without educated citizens embracing the concept of “symbiotic design” and personal involvement, we simply continue the same cycle of unhealthy consumerism and the irresponsible concept of a user society taped together by piecemeal, disconnected and ultimately failed green technology. This is why designs like pollution-cleaning concrete suggest a limited solution to a larger challenge. For instance, this technology could be construed by some as permission to keep polluting—something or someone else will take care of it, after all. It reminds me of one of my pet peeves: littering. And at its root is the lack of partnership and respect of the community and individual for his or her environment from his own back yard to some foreign city being visited abroad. Green concepts need to be fully embraced by the community in which they are applied. And this is best accomplished through the larger framework of green city planning and community education.

It isn’t enough to know the how; we need to know why to make it work. Educating the public and promoting community responsibility and involvement in green designs is key to achieving the necessary paradigm shift for future success. These can include from micro-elements (green rooftops; rain gardens; people’s gardens and curbside gardens; and green streets) to macro-elements, such as whole ecosystems/communities planned sustainably.

Despite some criticism by practical landscape architects, ecological architect Vincent Callebaut’s bold designs for future ecosystems are predicated on whole community involvement in sustainable practices. Examples of some of his bold subversive designs include Hydrogenase and Hyperions.

1. Hydrogenase: Vincent Callebaut’s Hydrogenase is an ambitious airship design powered by seaweed. The concept involves the production of biofuel from seaweed in a floating algal farm with solar cells and hydro-turbines to capture tidal energy; the algal farm, in turn, act as a hub for the elongated seed-shaped airship. The hub produces biofuel—essentially hydrogen—from the microorganism Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, which is able to produce oxygen through photosynthesis but in the absence of oxygen produces hydrogen and metabolites such as formate and ethanol through hydronenase enzymes. The algal farm recycles Carbon dioxide for the bio-hydrogen airship. The semi-rigid unpressurised airship stretches vertically around an arborescent spine that twists like chloroplast ribbons 400 meters high and 180 meters in diameter. Each Hydrogenase airship is covered with flexible inflatable photovoltaic cells and twenty wind turbines to maneuver and collect energy. The interior spaces provide room for housing, offices, scientific laboratories, and entertainment, and a series of vegetable gardens that provide a source of food while recycling waste.

2. Hyperions: Callebaut’s and Amiankusum’s “Garden Towers” of their Hyperions Project, is aimed at decentralizing energy and deindustrializing food. Hyperions consists of six interconnected and solar-paneled towers with hydroponic balconies for food production and large greenhouses on the top, with cooling airflow that imitates the climate control of a termite mound. The design is a “sustainable ecosystem in itself,” the architects claim.

References:

Aldersey-Williams, H. 2004. “Towards biomimetic architecture.” Nature Materials, vol 3(5), May. Online: https://www-nature-com.libproxy1.usc.edu/articles/nmat1119.

Badarnah, L. 2017. “Form Follows Environment: Biomimetic Approaches to Building Envelope Design for Environmental Adaptation.” Buildings, vol. 7(2), January. Online: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1939841182?pq-origsite=primo.

French, R.J. and Berhan M. Ahmed. 2010. “The challenge of biomimetic design for carbon-neutral buildings using termite engineering.” Insect Science, March.

Garcia-Holguera, M., O. G. Clark, A. Sprecher, and S. Gaskin. 2016. “Ecosystem biomimetics for resource use optimization in buildings.” Building Research and Information, vol 44(3), April. Online: https://www-tandfonline-com.libproxy1.usc.edu/doi/full/10.1080/09613218.2015.1052315.

Knippers, K. G. Nickel, T. Speck. 2016. Biomimetic Research for Architecture and Building Construction: Biological Design and Integrative Structures, 1st ed, pp 57-83. Cham: Springer International Publishing E-book: https://link-springer-com.libproxy1.usc.edu/book/10.1007%2F978-3-319-46374-2.

A. S. Y. Mohamed. 2018. “BIOMIMETIC ARCHITECTURE: Creating a Passive Defense System in building skin to solve Zero Carbon Construction Dilemma.” EQA, vol. 29, May. Online: https://eqa.unibo.it/article/view/7855.

Poppinga, C. Zollfrank, O. Prucker, J. Rühe, A. Menges, T. Cheng, and T. Speck. 2018. “Toward a New Generation of Smart Biomimetic Actuators for Architecture.” Advanced Materials, vol. 30(19), May. Online: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.libproxy1.usc.edu/doi/full/10.1002/adma.201703653.

Reichert, S, A. Menges, and D. Correa. 2015. “Meteorosensitive architecture: Biomimetic building skins based on materially embedded and hygroscopically enabled responsiveness,” Computer-Aided Design, vol. 60, March. Online: https://www-sciencedirect-com.libproxy1.usc.edu/science/article/pii/S0010448514000438.

Rivera, R. 1999. “Where you’ll live, work, and play in the 21st century.” Science World, vol 55(10), February. Online: https://search-proquest-com.libproxy1.usc.edu/docview/218134025?accountid=14749&rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

One thought on “Sustainable Architecture: Learning from Nature & Embracing the Magic of Symbiosis”