It started with my need for change. My need to discover. To witness beauty. That meant going outside. And I knew exactly where to go.

I made a lunch and took some snacks, saddled myself in Benny (my trusted VW steed) and drove west.

It was late October and the cold winds hadn’t yet cajoled the colourful leaves off the maples, aspens, birches and oaks. I knew I would witness something remarkable. I was in the north temperate zone of Canada, after all, and this was the height of autumn magic…

Soon, I was driving along one of my favourite country roads, a gently rolling barely paved road through forest and farmland that rose and fell over drumlins and eskers with views that make you sigh. A vibrant carpet of orange-crimson forest and copper-hued fields covered the undulating hills in a patchwork of colour.

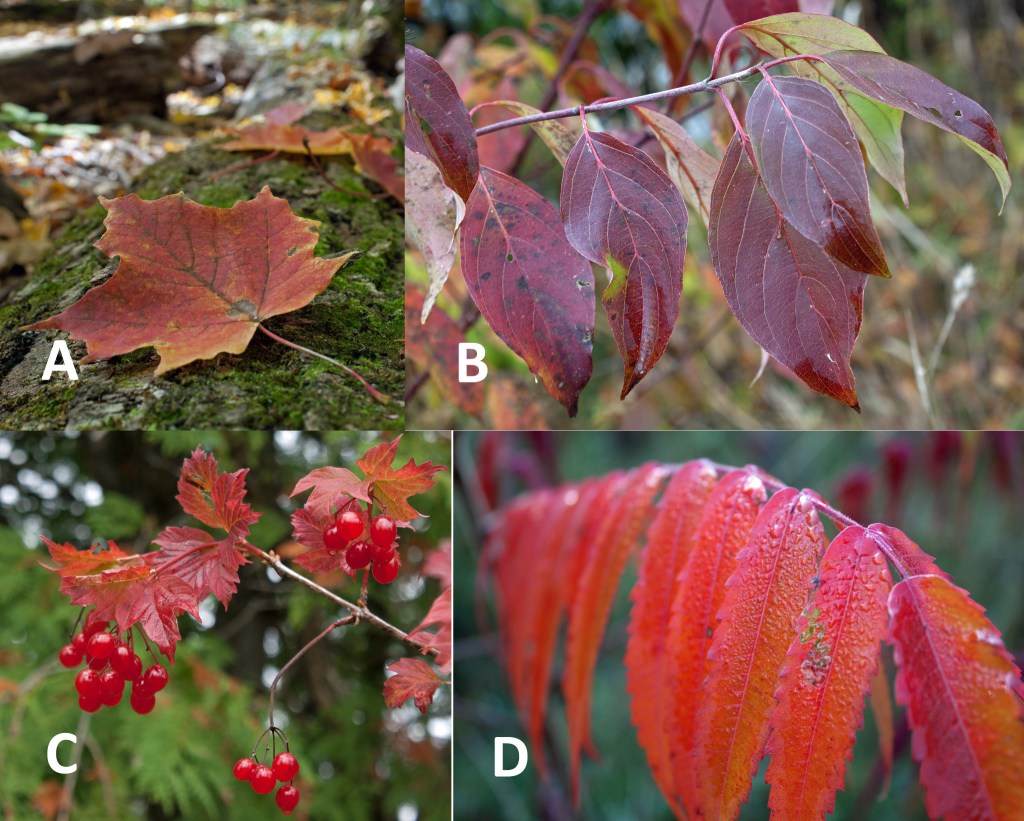

I stopped frequently and stepped out into the light rain to take photographs. The air was fresh and clean against my skin and I breathed in the scent of wet vegetation and loam. A light mist washed the distant hills in muted shades of a watercolour painting. The nearby forests were anything but muted. I drove past flaming thickets of red-purple dogwoods and sumacs. Benny took me beneath neon canopies: the brilliant orange and deep reds of sugar and red maples, the lemon yellows and bronzes of aspens, oaks and beeches.

The flaming colours signify approaching death. The deeper the colour, the closer to the end.

With less light in fall, the green sugar-making pigment, chlorophyll, starts to breaks down. Other pigments, previously masked by the chlorophyll are revealed: red-purples of anthocyanin and the oranges and yellows of carotenoids. Carotenoids are a family of pigments that include orange ß-carotene and yellow-orange xanthophylls such as lutein, which is yellow in low concentrations and orange-red in high concentrations, and yellow zeaxanthin, which converts to orange violaxanthin when triggered by the right circumstance.

Carotenoids are the same size as a bacterium and are an ancient class of pigments, thought to have evolved some three billion years ago. They have two main functions in the leaf: 1) they act as accessory pigments, helping to harvest light energy (in wavelengths where chlorophyll does poorly), which they then transfer to chlorophyll to manufacture sugar; 2) they also protect leaves from harmful compounds that are normal by-products of photosynthesis. Carotenoids help keep the balance between not enough and too much light by diverting excess energy and dissipating excess energy as heat. For example, acidic conditions of leaf stress that create by too much energy triggers the conversion of zeaxanthin into violaxanthin, which dissipates excess light energy as heat—a process that is reversible. As chlorophyll degrades in the fall, light striking the leaf may cause injury to its biochemical machinery, particularly the parts that regulate nutrient movement. Both the xanthophyll cycle and physical light shield provided by these pigments help the leaves efficiently move their nutrients into the twigs for the tree to use later.

According to the Smithsonian Institution, sugars trapped in the leaves that weren’t part of the leaf in the growing season, produce new pigments called anthocyanins, which create intense reds and purples found in some oaks, maples, mountain ash, sumac, viburnum, and dogwoods.

According to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, “Red pigments are produced during autumn to help shade leaf photosynthetic systems from bright sunlight. In many plants, the disassembly of leaf components in fall results in susceptibility to damage from bright light, particularly as temperatures decline. Protection from bright light during autumn is important because damage to the photosynthetic components during this time will reduce a plant’s capacity to recover nutrients from leaves. Plants that do not turn red in autumn are generally more resistant to the effects of bright light during this time, and therefore do not need to produce red pigments. The shading function of the red pigments explains why leaves exposed to direct sunlight are the brightest red, while leaves shaded within the canopy of a plant often show little or no accumulation of these pigments.”

As the temperature plummets, the trees build a protective seal between the leaves and their branches, taking in as many nutrients as possible from the sugar-building leaves; leaves won’t survive the winter and make trees vulnerable to damage if they remain. An exception is the marcescence (leaf-retention over winter) in leaves of beech, oak, and hophornbeam: another story.

Once the leaves are cut off from the fluid in the branches, they separate and drop to the ground, helped by the winds. There, the fallen leaves decompose and restock the soil with nutrients; they also contribute to the spongy humus layer of the forest floor that absorbs and holds rainfall. Fallen leaves are also food for soil organisms, whose actions in turn keep the forest functional.

As I wove through the deep colours of autumn, I felt humbled by this naked beauty, so simply given. So ingenuously revealed. How elegantly yet guileless nature went through its stages of dying to ensure renewal and growth!

Appalachian State University reminds us that “the beauty of fall color is not just an arbitrary act for our visual pleasure. Rather, the presence of these pigments shows that they are working to protect the leaf. If the leaves are protected as they die, that ultimately affects the health and vigor of the tree. Healthy trees, in turn, are the basis for maintaining healthy ecosystems. So, fall color may be a not-so-subtle signal of the health of our forests. And that is something worth knowing!”

I returned home, invigorated and humbled by nature’s transient show. Within weeks, the bright leaves would fall, leaving the trees bare and gray and the ground a thick slippery carpet of brownish gray-black rot. Beauty enfolded, dissected and integrated. Insects, fungi, and bacteria would deliver what the leaves used to be and create something else, a gift to the living forest.

Is that not what death is? The end of something to ensure the beginning of something else?

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

Krasno

LikeLike