The Ancient Forest Alliance (AFA) is a registered non-profit organization dedicated to protect BC’s endangered old-growth forests by implementing a science-based plan. I ran into some of their work when I traveled to Port Renfrew on Vancouver Island a few summers ago.

Aren’t forests a renewable resource? What’s wrong with logging old-growth forests as long as the trees are planted and grow back?

Trees can be a renewable resource, but old-growth forests are not. Depending on the timing of the last major disturbance (from fire or disease, for example), BC’s coastal old-growth forests are typically between 200 to 2,000 years in age. These forests are logged every 30 to 80 years, though, meaning that, under the short rotation ages and management regimes practiced in BC, they will never become old-growth again. The issue is therefore not whether or not trees grow back, but whether or not the ensuing second-growth tree plantations adequately replicate the original old-growth forests. The fact is, they don’t. (See next question).

Isn’t it better for the climate if we cut down the old-growth forests and replace them with healthy, faster-growing, young trees?

No. Scientific research shows that old-growth forests are not only massive storehouses for carbon, they also continue to grow and sequester vast quantities of carbon over their lives (contrary to logging industry propaganda). More importantly, in terms of the amount of carbon stored at any given point of time, BC’s old-growth forests contain two to three times more carbon per hectare than the ensuing second-growth tree plantations that they are being replaced with. When an old-growth forest is logged, much of the carbon is released in the form of decomposing wood waste in clearcuts and not long afterwards as discarded paper, cardboard, crates, and other wood products in landfills, creating methane, and as toilet paper in the sewage systems. Only a small fraction (typically about 20%) of the carbon removed from logging an old-growth forest ends up in longer-lasting wood products, such as in furniture or buildings. The rest of it is released into the atmosphere within a relatively short length of time. In a few cases, second-growth plantations may grow faster than old-growth forests, but these smaller, fast-growing trees are simply working to “get back” or “reabsorb” the carbon lost from logging the original old-growth forests. This carbon is never fully absorbed, though, because it would take 200 or more years to re-sequester all the carbon that was released, and rotation ages are only 30 to 80 years on the coast. In addition, even if rotation ages were 200 years, the climate crisis doesn’t have 200 years to wait. Ultimately, there is a massive net release of carbon when old-growth forests are replaced with second-growth tree plantations, even if those plantations grow faster than old-growth forests.

Think of it this way: imagine that you are unemployed, but nevertheless have an inheritance of tens of millions of dollars – similar to the millions of tons of stored carbon that we’ve inherited in our old-growth forests. If you spent all your inheritance money and then got a job, would you be better off financially than when you were unemployed? Of course not. Your job would simply be a means to make back the money you lost by spending your inheritance. Similarly, fast-growing tree plantations are simply working to get back the carbon in the atmosphere lost by logging the old-growth forests we’ve inherited – except they never get all the original carbon back due to the short rotation ages.

Isn’t there still a lot of old-growth forest left in BC? That’s what the provincial government says.

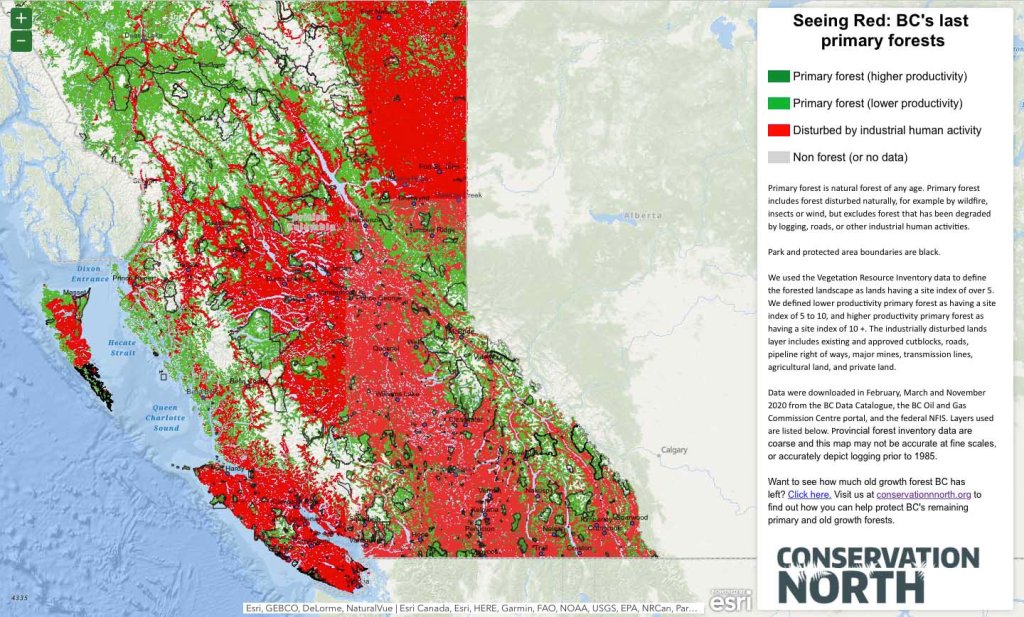

The BC government’s old-growth statistics typically inflate the amount of remaining ancient forests by including stunted, marginal, and often “unloggable” old-growth forests found in low-productivity bogs; rocky landscapes; and high-altitude, subalpine, mountainous regions where growth rates are extremely slow, resulting in small trees of low to no timber value. Today in BC, there is far more low-productivity, economically “unloggable” old-growth forest than productive old-growth forest with large trees of high economic value for forestry. These critical distinctions are typically not made in the BC government’s statistics.

In addition, BC government statistics tend to find ways to “ignore” vast areas of previously logged old-growth forests, to make it appear that a far larger fraction remains. For example, on Vancouver Island, there are over 600,000 hectares of private lands, the vast majority of which were previously managed by the provincial government under the same regulations as public lands until recent times, and which are currently managed by the BC government through private lands regulations. These lands constitute about one-fourth of all productive forest lands on Vancouver Island – and virtually all old-growth forests have been logged there under provincial management. By conveniently ignoring these lands in their statistics of remaining old-growth forests, it appears that the situation is not so dire – that a relatively smaller fraction of the land base has been logged. This is simply not so. In fact BC’s old growth forests have been nearly eliminated.

What does the Ancient Forest Alliance do?

The AFA is a non-profit BC environmental organization working to protect the province’s endangered old-growth forests and ensure a sustainable, second-growth forest industry. We work to educate and mobilize British Columbians in order to pressure politicians to achieve our goals. We explore and photograph endangered old-growth forests; garner major news media coverage to inform the public; organize hikes, slideshows, and rallies; build support among key allies including First Nations, businesses, unions, faith groups, and others; build boardwalks and hiking trails in ancient forests; lobby politicians; and write and produce large amounts of educational materials in brochures, online, and with videography.

How can I get involved?

Along with more donors, we need volunteers to help us put up flyers, distribute brochures, staff booths at events, phone supporters for rallies and events, and help build boardwalks. You can also help the campaign by spreading the word to family, friends, and colleagues, attending AFA events, and by taking action at critical points in time – for example by sending a message to decision-makers or contacting your local MLA. Subscribe to our newsletter and/or follow us online to stay informed about upcoming action alerts.

For more questions and answers go to this page of the Ancient Forest Alliance.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.