Here are my five reasons:

1. Bogs are Unique Environments

Bogs are freshwater wetlands with unique conditions such as being oxygen-poor and nutrient-poor. Bog soil—called histosol—is spongy and made up of partially decayed plant matter called peat. These conditions call for specialized life that can survive—in fact thrive—in acidic, waterlogged soil. Bogs are characterized by substantial peat accumulation (over 40 cm), high water tables and acidic-loving vegetation. Canada has 35% of the world’s peat accumulating wetlands (peatlands).

Most bogs are dominated by the actions of Sphagnum, which is known as the ‘bog builder’ because it holds water, lowers oxygen levels and secretes acid, keeping conditions suitable for peat formation and specialist plants. Sphagnum acts like a giant sponge, absorbing rainfall and releasing it slowly; it can absorb up to 20 times its own weight in water, holding it in specialized empty cells. Sphagnum actively maintains a pH of 3.0 to 4.5 by creating cation exchange sites (uronic acid polymers) loaded with H+. The dry mass of Sphagnum contains from 10% to 30% uronic acid. The uronic acid polymers take up base cations, mostly ions such as calcium and magnesium, and in exchange releases hydrogen ions (acid ions).

While bogs may range greatly depending on several factors, all bogs have several things in common as wetlands. All bogs:

- Have a high water table

- Are strongly acidic (often pH of less than 4) and often anoxic

- Are nutrient-poor (oligotrophic or dystrophic)

- Have Sphagnum and peat, usually thicker than 40 cm

- Receive most of their water and nutrients from precipitation (ombrotrophic) as opposed to from surface or groundwater input (minerotrophic)

2. Bogs Support Weird Life

Because of its unique environment, many bog inhabitants such as plants, animals, fungi and lichen have highly specialized adaptations to poor nutrients, waterlogging, acidity, and lack of oxygen. Plant adaptations to flooding and anoxic conditions include aerenchyma (spongy tissue with spaces), floating growth forms, and shallow root systems. Bog shrubs are often evergreen, which may help to conserve nutrients. Other strategies of bog plants to conserve nutrients include forming symbiotic associations with fungi (through mycorrhiza) and carnivory.

Bogs typically support Sphagnum and ericaceous shrubs such as bog myrtle, which has fungal-infested root nodules for nitrogen fixation. Rhododendrons and orchids also use their symbiosis with fungi in their roots (called mycorrhizae) to get extra nutrients. Carnivorous plants such as sundew, bladderworts and pitcher plants get their nutrients (particularly nitrogen) by trapping insects. Prey are attracted by the sweet sticky liquid on or in the leaves and get stuck. The plant then produces digestive liquids and adsorbs the dissolved insect remains. Labrador tea’s thick, waxy and hairy downward-curled leaves with fuzzy undersides help the plant hold on to moisture by creating barriers to water loss. Bog laurel has similar evergreen leaves to minimize water loss; their leaves are leathery, shiny with smooth edges turned down with undersides that have fine white hairs. The bog cranberry is adapted to survive long periods of anoxia, conditions prevalent in bogs.

3. Bogs are Very Old

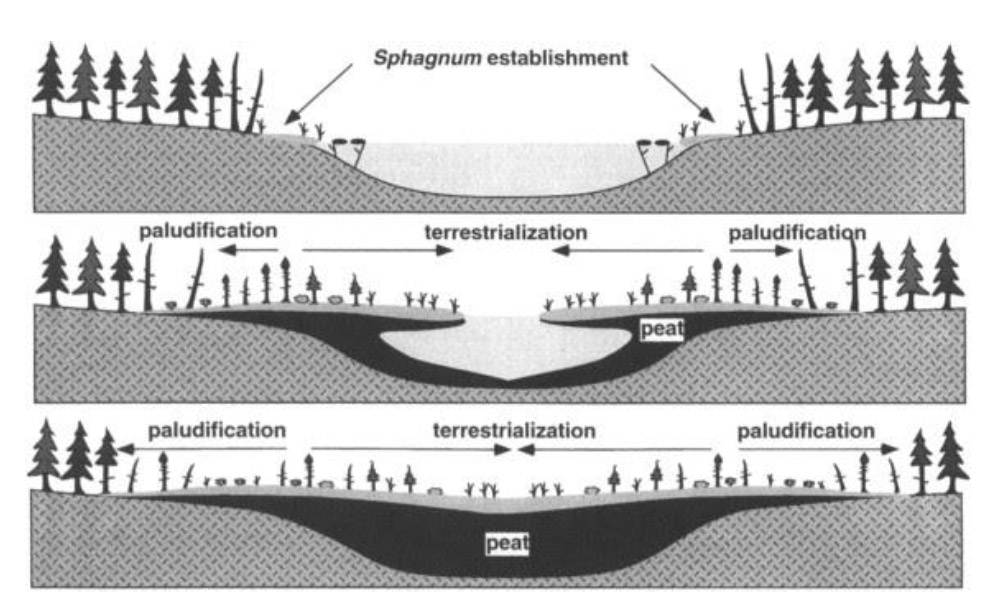

Many bogs lie in depressions created by melting ice blocks buried during glacial retreat over 10,000 years ago. Organic debris accumulated in these ancient lakes, converting them into peat bogs, some over 50 feet deep. Some bogs formed instead in sloughs and depressions with no drainage. Bogs form by two processes, both taking hundreds or thousands of years to develop: one way is the filling of a shallow lake with plant debris as Sphagnum moss grows out from the lake’s edge (called terrestrialization); the other is when Sphagnum moss blankets a terrestrial ecosystems by overgrowth of bog vegetation, creating organic matter and creating water-logged conditions by preventing precipitation from evaporating (called paludification).

For example, Camosun Bog in Vancouver, BC, developed when the Vashon glacier retreated 12,500 years ago and left a depression that developed into a prehistoric lake, which slowly filled in with plant debris over thousands of years. Peat-forming Sphagnum mosses along the edges of the lake likely helped escalate the lake infilling with plant debris along with an outward accumulation of organic matter at the shorelines and its first peat deposits laid from four to six thousand years ago.

Initial root masses of bog peat likely developed over the lacustrine mineral deposits as the transition from sedge-dominated marsh to limnogenous fen took place. The plants eventually choked out the inflows, depleting the oxygen and nutrients the inflows carried. Soil conditions became increasingly acidic from the production of humic acid during decomposition of plant debris and from active cation exchange by Sphagnum mosses.

With anoxia and increased acidification (low pH of 4 or less), the rate of decay was reduced and impeded the drainage of the lake, leading to water-logged soil conditions.

These conditions discouraged the growth of vascular plants but were perfect for Sphagnum moss, which took over. Peat accumulated as minerotrophic peat at first as water passed over or through mineral parent materials. As the peat layer grew higher, the vegetation became progressively more isolated from the mineral-soil-influenced groundwater and received water only through precipitation (ombrotrophic peat). As bog succession continued, the perched water table in the peat became isolated from the water table of the local terrain, and the bog was unaffected by runoff or groundwater from the surrounding mineral soil. The sponge-like acidic properties of Sphagnum maintained this true bog’s climax community for thousands of years.

4. (Some) Bogs are Famous & Tell Stories

The world’s largest wetland is a series of bogs in the Siberia region of Russia. The Western Sibrian Lowlands cover more than a million square kilometers and the largest single bog in the world is the Great Vasyugan Mire in the central Western Siberian Plain. Named after the river Vasyugan, the mire formed after the recession of the glacier during the last Ice Age, some 10 thousand years ago. Often referred to as the second “green lungs” of the world after the Amazon Rainforest for its ability to absorb carbon, the Great Vasyugan Mire holds global importance; in 2017 the Vasyuganskiy Nature Reserve was created to protect it.

Because of their unique preserving environment (oxygen-free, low mineral content and excessive tannins), bogs can preserve human corpses, several of which have turned up in various bogs to reveal mysterious histories of ancient times. Britannica includes nine examples of noteworthy bog bodies, all killed violently as human sacrifices. The Yde Girl, is a sixteen year old girl from around 170 BCE, who died from stab wounds and found in a bog near the village of Yde, in the Netherlands. Weerdinge Couple were executed around 160 BCE, found in Bourtanger Moor in the Netherlands. Eiling Woman died by hanging around 280 BCE, found in Bjældskovdal bog, Denmark. Koelbjerg Man died around 8000 BCE near Odense, Denmark.

The Tollund Man was hung in a ritual sacrifice around 280 BCE (early Iron Age) and was found in Bjældskovdal bog, Denmark; he is the best preserved bog body found so far. “To the people who put him there,” writes Smithsonian Magazine, “a bog was a special place. While most of Northern Europe lay under a thick canopy of forest, bogs did not. Half earth, half water and open to the heavens, they were borderlands to the beyond.”

5. Bogs have Many Forms & Strange Names

Bogs come in all shapes and sizes, from the extensive blanket bogs of Flow Country to tiny quaking bogs. Distinct types of bog habitats include the following:

Upland and Lowland Blanket Bogs are shallow bogs (from 50 cm to 3 m on average) that develop through paludification in highland areas with significant rainfall: the bog “blankets” an entire area, including hills and valleys forming patterned surfaces of pools, flat and sloped areas, flushes and swallow holes. Paludificaion may be induced by climate change, construction of beaver dams, logging of forests or by the natural advancement of peatland. The spread of blanket bogs (also known as blanket mire or featherbed bog) in the northern hemisphere has been traced to deforestation by prehistoric cultures. Wet, acidic conditions created by blanket bogs may kill or stunt trees, allowing bog species to persist. The Flow Country in Scotland is considered the largest blanket bog in the world. Along with associated heath and open water, its international importance as habitat for diverse and unusual breeding birds is recognized.

Quaking bogs develop through the terrestrialization of kettle lakes, gouged out depressions and dammed valleys. A bog mat (thick layers of vegetation) gradually develops from the edges, migrating toward the middle of the lake and soon consolidated by Sphagnum moss and other bog plants. Often about a meter (3 feet) thick on top, peat continuously accumulates, isolating the plants from their nutrient supply and the bog becomes increasingly nutrient poor. Quaking bogs bounce when people or animals walk on them, giving them their name.

Raised Bogs are vaguely dome-shaped, as decaying vegetation accumulates in the center. They form through terrestrailization in old glacial lake basins or in shallow plains. These bogs are characterized by their convex surface and pools of water encircling the central area. They are also called ombrotrophic bogs that are acidic, wet habitat poor in mineral salts and exclusively fed by precipitation (ombrotrophy) and mineral salts introduced from the air. Peat deposits fill the entire basin and isolate the bog from groundwater sources.

String Bogs have a varied landscape, with low-lying “islands” and ridges interrupting the saturated bog ecosystem. Woody plants alternate with flat, wet sedge mats. String bogs occur on slightly sloping surfaces with the ridges at right angles to the direction of water flow. Also known as aapa moors or aapa mires (Finnish) or Strangmoor (German). String bogs form in northern Canada due to differential rates of peat accumulation. They have pools of water between ridges of peat.

Valley Bogs develop in wet shallow valleys. The valleys experience some downstream impedance, or badly drained hollows. According to Oxford Reference, many European valley mires have layers of charcoal in their stratigraphy below the peat, suggesting that fire may originally have initiated peat formation by creating a charcoal deposit that effectively seals off basal soils from water penetration and causes waterlogging. The groundwater is base-poor and conditions are acidic. This type of mire is flow-fed (rheotrophic), so technically it is a poor fen type of community rather than a true bog. An example in Canada is the Mer Bleue peatland, a 25-km2 raised, ombrotrophic bog situated in the Ottawa River Valley

Check out my articles on the various bogs I’ve investigated in Canada so far:

- Camosun Bog, located in the heart of Vancouver City, developed from a sedge marsh into an ombrotrophic peatland, which suffered from recent development but is undergoing restoration through the re-introduction of Sphagnum and associated bog plants such as Labrador tea, bog laurel, sundew, and bog cranberry.

- Catchacoma Bog / marsh, located in the Catchacoma old-growth Forest in the northern Kawartha area of Ontario, is a Sphagnum-rich minerotrophic bog/swamp and swamp thicket on the edge of a larger mineral meadow marsh. Likely formed through paludification, this mire or nutrient-poor fen is possibly flow-fed (rheotrophic) with several characteristic Sphagnum species, pitcher plant, and speckled alder.

References:

Britannica. 2024. “Bog / Wetland”

International Peatland Society. 2022. “Types of Peatlands.”

Irish Peatland Conservation Council. 2017. “Blanket Bogs”

Jenkins, Jerry. 2020. “Mosses of the Northern Forest: A Photographic Guide.” Cornell University Press, Ithaca. 169pp.

Le, Andrea. 2020. “Groundwater Elevation and Chemistry at Camosun Bog, British Columbia, and Implications for Bog Restoration.” Master of Science Thesis, Simon Fraser University, 64pp.

National Geographic. 2023. “Bog”

Rydin, Håkan and John K. Jeglum. 2013. “The Biology of Peatlands.” Oxford University Press.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.