I’ve been visiting Catchacoma old-growth forest and associated wetland for several years. I recently discovered a granite outcrop that formed a kind of peninsula jutting out into the meadow marsh; the rock, which I named Catch Rock, was covered in lichen and moss and I decided to study it. During my visits there, I also discovered two species of club moss, both strange ‘beasts’ that clamoured for my attention from the lichens I was studying.

Club Mosses that I Found

Diphasiastrum complanatum: I found 4-inch high colonies of this club moss perched on the shallow soil-covered rock under the pines, oaks and hemlocks. They had a branching whorled arrangement with flat closely set scale-like leaves that resembled cedar leaves. Several plants had stalks with a strobilus (spore cone) that reached for the sky to release their spores. I identified this club moss as Diphasiastrum complanatum (previously under Lycopodium complanatum). This native to dry coniferous forests across Canada is commonly called northern running pine, stag’s horn moss, and, my favourite, ground-cedar—for its strong resemblance to cedar leaves.

Dendrolycopodium obscurum: I found this 5-inch tall plant with underground-running stems cozying with Bog Haircap moss (Polytrichum strictum) on a bed of Sphagnum moss of the wetland next to Catch Rock. I identified this clubmoss as Dendrolycopodium obscurum (formerly under Lycopodium obscurum, a native of moist woods and bog margins throughout Canada. It is also called ground pine, princess pine or rare clubmoss. When I first saw this delicate plant, I thought it resembled a miniature conifer, with tiny needle-like leaves (called microphylls) arranged in whirls around its tiny branches. In fact, I was looking at the aerial branching shoots of the plant’s sporophyte; its main stem is a creeping rhizome underground. Several of the main branches held erect strobili for spore release. Another species, Hickey’s Tree Clubmoss (Dendrolycopodium hickeyi), is a real lookalike, also resembling a conifer sapling; it is best distinguished from D. obscurum by its micro leaf arrangement. D. hickeyi has leaves the same length around its branches, while D. obscurum has smaller leaves on the underside of its branches. In cross-section, D. hickeyi branches are round while D. obscurum are elliptic or semi-circular.

.

A previous survey of Catchacoma Forest and wetland identified four species of club moss; two of them I found. The two that I have yet to find are: Running Club-moss (Lycopodium clavatum) and Shining Fir-moss (Huperzia lucidula). I’ve probably seen but not recognized Huperzia during my walks in the moist hemlock forest, its preferred habitat.

.

Club Mosses Are NOT Mosses

Club mosses are, in fact, not mosses at all. They belong to a seedless vascular plant family Lycopodiaaceae, closely related to ferns. And, like ferns, club mosses reproduce by releasing a large amount of tiny spores—usually from club-shaped structures like the strobili I found on both specimens I saw. Long-lived evergreen plants that resemble miniature conifer trees are native to moist woodland habitats in North America.

From Tree Ancestors to Today’s Diminutive Club Moss

.

Today’s club moss is a miniature descendant of a once diverse plant lineage of ancient lycophytes that dominated the understory of the coal swamps of the Paleozoic forests.

.

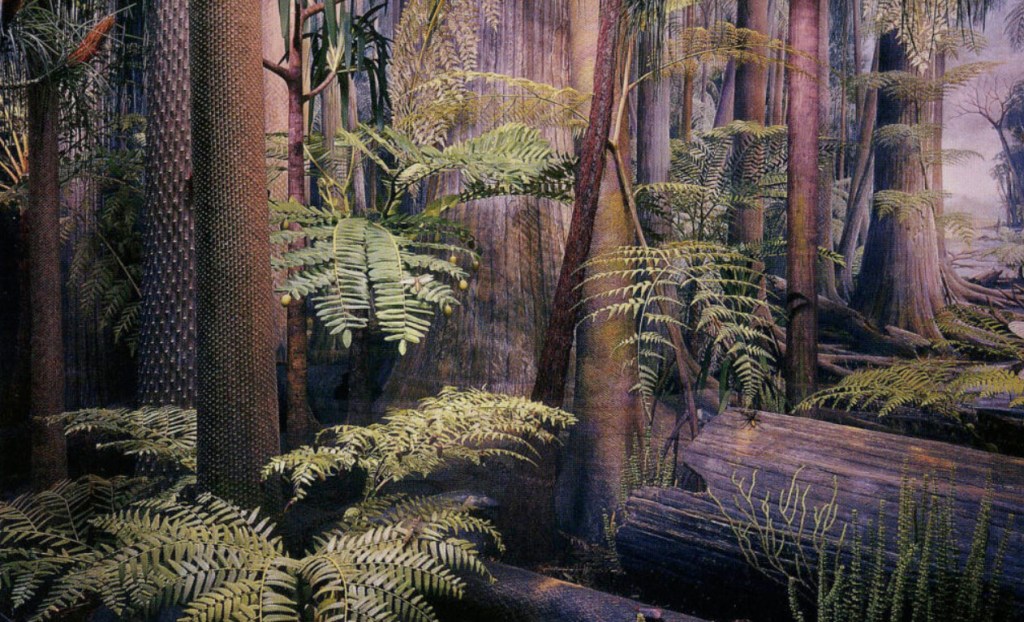

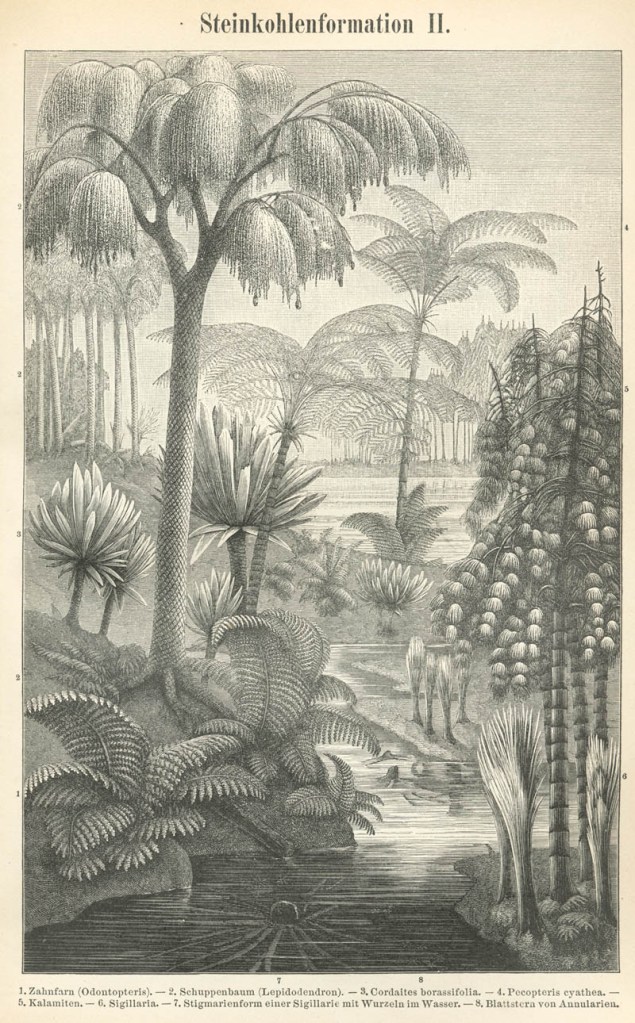

Their evolution and legacy is similar to today’s less than metre-high Equisietidae (horsetail family), whose predecessors were 20-metre high Calamites of the coal forest. Imagine these prehistoric swamps, buzzing with giant insects, and dense with algae, filter-feeders, and amphibian-like tetrapods. Out of these murky lowland swamps emerged forests of bizarre trees such as giant club mosses (arborescent lycopsids such as Sigillaria and 50-metre high Lepidodendron); tree ferns (Psaronius), seed ferns (Medullosa) that looked like palm trees with seeds as large as avocados; and giant tree horsetails (Calamites).

.

Arborescent Club Mosses (Giant Lycophytes) began during the Mississipian and proliferated during the Pennsylvanian of the Carboniferous Period. These lycophytes lived in the steamy ‘equatorial’ rainforest swamps that covered the vast continent and coastal shallows of tropical Laurasia (Europe, Asia, and North America) and Cathaysia (mainly China) during the Carboniferous Period. Warm and humid coastal shallows accumulated large amounts of peat, rich in stored carbon.

.

The Age of Oxygen & Giant Everything

.

According to National Geographic, the growth of the Carboniferous swamp forests gave off oxygen and removed huge amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, burying the plants under the swamps and the carbon along with them. Atmospheric carbon dioxide eventually dropped and atmospheric oxygen levels peaked to around 35 percent, compared with 21 percent today. High oxygen levels allowed plants and animals to reach sizes not known in today’s atmosphere and to further diversify. Insects, which breathe by the diffusion of air through their exoskeletons, rather than using lungs or gills, exploited the surplus oxygen to grow to immense sizes. Gigantic insects thrived in the forest swamps of the Carboniferous. Three-metre (10 ft) long poisonous millipedes (Arthropleura) crawled among giant cockroaches and scorpions a metre (3 ft) long. Mayflies were abundant and dragonflies grew to the size of seagulls; the wingspan of Megalneura reached 2.5 ft. Many amphibians were predatory species that resembled modern-day crocodiles. Armed with vicious teeth, they reached lengths of almost six metres (20 ft). Amphilbamus, Phlegethontia and Eryops had large skulls, small trunks and stocky limbs.

.

Club Mosses (Lycophytes) Dominated the Coal Forests

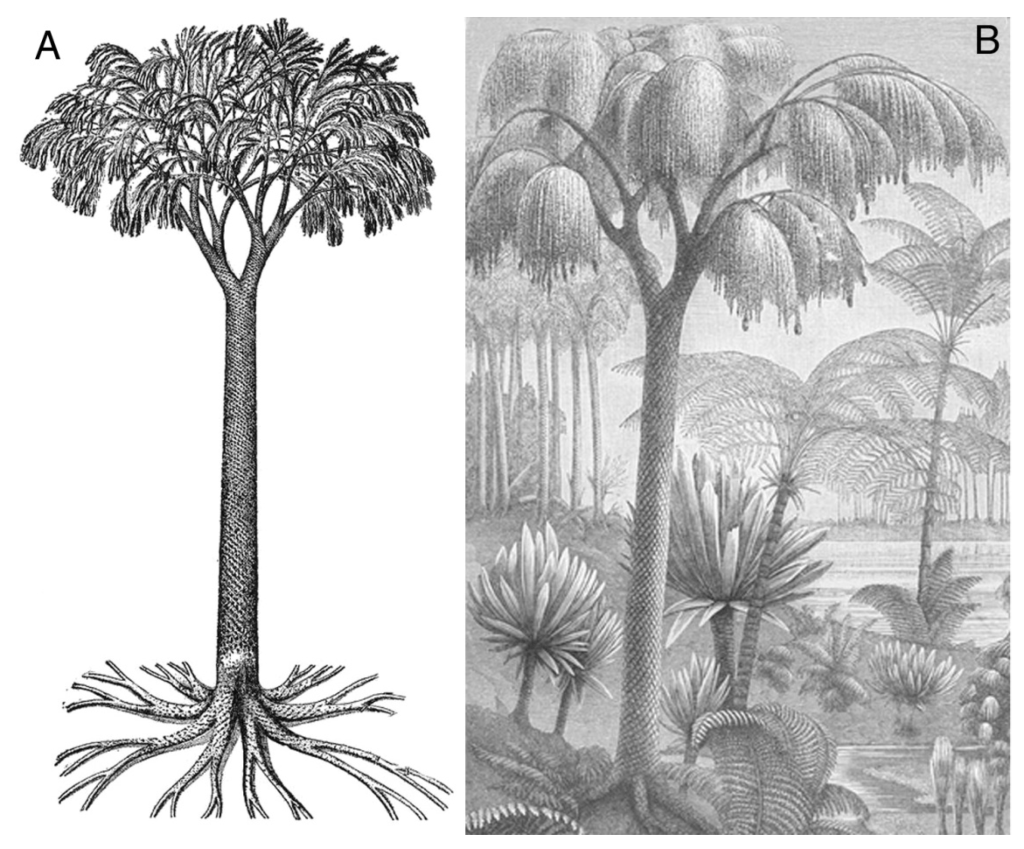

Earth History describes how the Carbonifrous swamp forests were dominated by giant club mosses, particularly Sigillaria (with ribs and round leaf bases) and Lepidondendron or Scale Tree (with diamond-shaped leaf bases (or leaf scars), arranged in rows of ascending spirals. In Defense of Plants explains that the name ‘scale tree’ “stems from the fossized remains of their bark, which resembles reptile skin more than it does anything botanical.” According to fossil logs, Estrellamountain.edu describe the leaves of Lepidondendron as simple and resembling blades of grass; they were spirally arranged up the entire stem; as the plant grew, older leaves fell off, leaving diamond-shaped scars where they once attached. Lepidondendron reached 50 meters high and its photosynthetic trunk reached nearly 2 meters in diameter.

.

Earth History describes these 30-50-metre high tree-like ‘mosses’ as having, “almost no woody tissue. Instead the trunk was filled with pith and strengthened by a thick cortex, which extended from the cambium outwards to a bark-like, decay-resistant periderm. Long grassy leaves grew from the trunk, and following leaf-fall the scars on the leaf cushions composed a distinctive geometric pattern. In contrast to the brown, non-photosynthetic stems of modern trees, photosynthetic bark covered the whole trunk. Only towards the end of their lives did they form lateral branches and put out a leafy crown, to reproduce before they died, by means of spore-bearing cones.”

.

As with the alder tree of today (which creates silt-roots for oxygen intake and whose wood can withstand being under water without rotting), the ancient club moss tree roots that anchored to peat were designed to float and were hollow. In Defense of Plants describes these ‘stigmaria’ as “large, limb-like structures that branched dichotomously in soil. Each main branch was covered in tiny spots that were also arranged in rows of ascending spirals. At each spot, a rootlet would have grown outward, likely partnering with mycorrhizal fungi in search of water and nutrients.” As their watery habitats dried out toward the end of the Carboniferous Period, the arborescent lycophytes died out; horsetails and tree ferns rose to dominate the late Carboniferous into the Permian.

.

What Happened to the Coal Forests of the Carboniferous Period

By the end of the Pennsylvanian, club mosses Lepidodendron and Sigillaria declined and became extinct by the end of the Permian Period around 252 million years ago. After millions of years of heat and pressure, the buried remains of club mosses and other giant plants of its ecosystem, were transformed into coal reserves. The anoxic conditions of the swampy environment and the lack of microorganisms to break down the plants (they hadn’t evolved yet!) prevented the plant material from decaying; instead, the dead plant material formed peat (as in our current bogs and fens), which held in the carbon they had taken in. Given the lack of a decay process, no carbon was released and instead this energy was locked in the coal forest for millions of years. Yielding to heat and pressure and sedimentation events from inundating seas, the forest peat biomass transformed to coal and this was ultimately released through mining by humans millions of years later.

.

Club Mosses Today

Lycopodium is currently a cosmopolitan genus with about 400 species found in many habitats and with a varied anatomy. Most are no more than 6-inches tall, a major reduction from their 100-foot high arboreal ancestors. Lycopodium is one of the oldest plants on earth; never evolving into flowering plants and still reproducing through spore release in the form of a dusty powder. Nina Veteto at Blueridge Botanic shares that the high fat content of the powder is highly flammable and was used to create gunpowder, fireworks, and flash powder for old camera flashes. Nirmita Sharma of microbenotes.com writes that Lycopodium is also traditionally used in homeopathy and herbal medicine; it is believed to have diuretic, laxative, and tonic properties. Some species are used to treat digestive disorders and their spores are used as a powder for coating pills and as a dry lubricant.

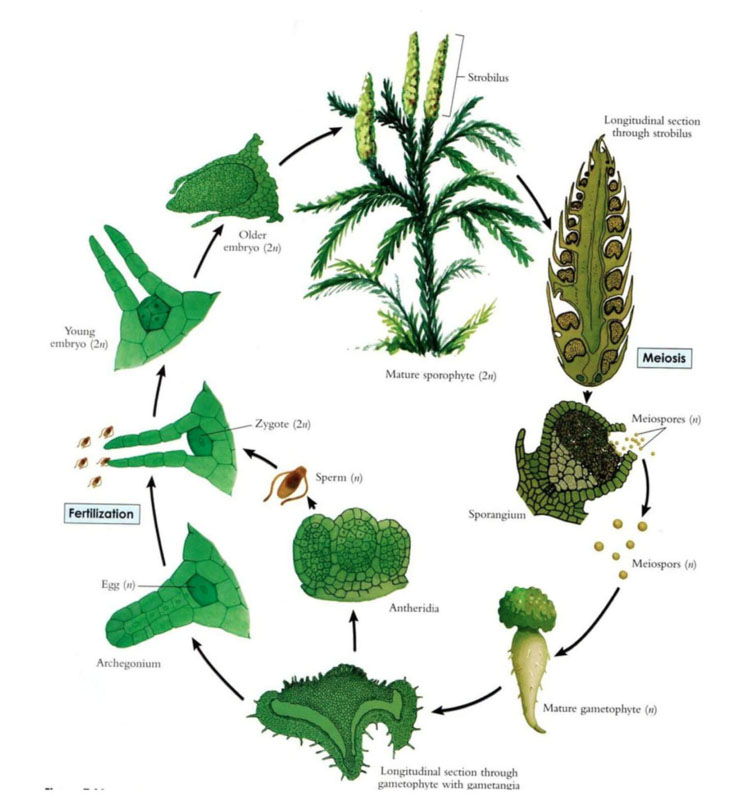

Lycopodium reproduces asexually through modified vegetative structures (e.g. formation of gemmae of bulbils), fragmentation (like many lichens), formation of resting buds, root tubercles, and adventitious buds. Sexual reproduction occurs in the sporophyte, through the strobilus that produces sporangia, specialized structures where spores are formed by meiosis. These gametophytes mature, forming antheridia that contain sperm and archegonia, which contain eggs. Fertilization occurs in the presence of water. The spermatozoids swim and reach the open archegonial neck of the gametophyte, and when it reaches the egg, fertilization takes place, forming a zygote which turns into an embryo that eventually becomes a mature sporophyte.

.

According to many scientists, we are currently experiencing the sixth extinction event. Also called the Holocene-Anthropocene Extinction, some call what is happening a “biological annihilation.” Scientists agree that the present extinction rate is thousands of times higher than the natural baseline rate. The baseline is about one species per every one million species per year; currently that rate is one in a thousand. This translates to 10,000 to 100,000 species becoming extinct each year.

Most scientists agree that the sixth mass extinction is caused by human activity (which includes unsustainable use of land, water and energy) and human-induced climate change. Extreme global biodiversity loss over the past 50 years has been mostly driven by habitat destruction to do with clearing of forests for farmland, the expansion of roads and cities, logging, hunting, overfishing, water pollution and transport of invasive species around the globe.

Will we survive the planet’s 6th Mass Extinction? I’m not sure. But I’m betting that what follows (as with all previous extinction events) will be grand. And maybe that post-apocalyptic world will include giant 100-foot high lycopods of some kind…

.

References:

Candeias, M. 2021. “The rise and fall of the scale trees.” In Defense of Plants, February 27.

Earth History. Year. “A New Approach to Earth History.” Earth History.

Hance, Jeremy. 2015. “How humans are driving the sixth mass extinction.” The Guardian, October 20, 2015.

Lorenz, Alex. 2022. “Club Mosses and their Mighty Ancestors.” Nature Museum.

National Geographic. 2015. “Carboniferous Period.” National Geographic.

Sam Noble Museum. 2018. “Fossil Lycophytes.”

Wagner, Warren & John T. Michel. Year. “Lycophyte”. Encyclopedia Britannica.

Waggoner, Ben, et. al. 2002. “The Carboniferous Period.” UCMP Berkeley.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.