.

“Lichens are right in front of our eyes. Everywhere,” writes Joe Walewski in Lichens of the North Woods. That whitish or green smudge on the trees in your backyard. That dark olive-brown crud on the ground amid the moss. A splash or yellow on rocks or cement, A blue-green smear on the street or tree. A black-green fuzz on the roof or brick of your house. We see them; we just don’t recognize them.

Lichens are literally everywhere: from the plaster wall of an ancient church in England to a fence post on a rural road in Ontario to the leaves of a tropical rainforest of Costa Rica or inside a rock in the Antarctic.

“Lichen are perhaps the most ‘obvious’ overlooked component of our landscape,” says Walewski.

.

We may not even notice lichen but many animals rely on them in various ways: Ruby-throated Hummingbirds use Shield Lichen (Parmelia) in nest construction for camouflage. Northern Parula Warblers construct nests by weaving strands of Beard Lichens (Usnea). The green Leuconycta moth protects itself from predators by looking like lichen. So many other animals eat lichen: Spruce Grouse, White-tailed Deer and moose, squirrels, mites, springtails, and slugs and snails, among many others. Painted lichen moth caterpillars can only eat lichen. Migratory caribou of the boreal and arctic rely on lichen (Cladonia spp.) as critical winter forage, readily digesting this high-energy food that is available to them when many other sources aren’t. A 2018 study by Joly & Cameron showed that lichens made up over 70% of the late winter diets of caribou in northwest Alaska. Caribou will eat about three kilograms of lichens in a day, ‘cratering’ through two feet of snow to find them.

.

.

Walewski suggests that a lichen is not so much an organism as a lifestyle. They are “Nature in miniature.” Lichenologist William Purvis calls them a “mini-ecosystem.” And a highly successful one, given that lichen have populated the entire planet. Eight to ten percent of terrestrial ecosystems are thought to be dominated by them. While some suggest there are about 18,000 species of lichen, according to Purvis there are more like over 30,000 different species of lichen inhabiting our planet. With the continued discovery of evolutionary adaptations and additional symbiotic partners in play, I tend to agree with Purvis.

.

.

Lichen are the first colonizers of bare rock and new soils. Succession on rock begins with crustose lichen (e.g. Acarospora, Porpidia, Rhizocarpon, and Lecidea). Rock shields (Xanthoparmelia) are common foliose lichens that follow, leading to more foliose and climax fruticose lichen (e.g. Phaeophyscia, Parmelia, Cladonia) along with companion mosses.

.

.

Mats of Cladonia and Stereocaulon may cover from 50-90% of northern environments. Lichens date back to the Early Devonian Period, some 400 million years ago. Several hundred-year-old lichen are commonly reported. Ages of up to 4500 years were reported for the crustose Yellow Map Lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum) in Greenland and Swedish Lapland. These pioneers of young landscapes degrade rock surfaces and prepare them for mosses, grasses and trees. Lichens that have cyanobacterial photobionts can grab nitrogen from the air, adding to soil fertility and helping regulate the nitrogen balance in the air. Light-coloured ground lichen such as Reindeer Lichen (Cladonia) help regulate temperature (reduce heat loss in winter and cool soils in summer) by reflecting heat and forming cryptogamic crusts* in terrestrial ecosystems that stabilize soil, fix nitrogen, raise albedo, and enhance soil water holding capacity. Together with mosses, lichens sequester carbon, regulate water tables, and prevent soil erosion.

.

.

As the earliest colonizers of terrestrial habitats on the earth, lichens are among the most successful forms of symbiosis. Part of their success lies in their versatility and shapeshifting qualities (more on this in another article) that includes a vagrant lifestyle for some (aka tumbleweeds) and an incredible diversity in shape, texture and colour—even within the same lichen organism—called a photomorph (more on that in another article too).

What makes a particular lichen grow here and not there?

Lichen is all about relationship—with itself (between its fungal and algal or cyanobacterial self)—but also with the substrate (whether living or not) on which it colonizes, and the changing and cycling environment around it such as light, temperature, moisture, nutrients, air quality, elevation, competition by other lichen and interactions with other organisms, and pollution (e.g. smog). Lichen get their water and nutrients from their surrounding environment via air and rain, and sometimes the substrate itself by absorbing it through any part of their thalli; lichens with root-like structures called rhizines use them only to anchor to a substrate.

.

.

Air Quality: Given that lichen get most of what they need from their surrounding air, its quality is an important factor in lichen growth. A neat example of how air quality can affect the growth of a particular lichen is given by Purvis in his book Lichen. Purvis reported that trees located near a cement quarry developed lichen communities typical of those on calcareous rock. It’s called the ‘alkaline dust’ effect.

.

.

Substrate: Anything that holds still long enough for a lichen to attach and grow is pretty much a suitable substrate. Soil, rocks, trees, leaves, debris, buildings, cars can all be substrates. Important features of the substrate to the lichen include its texture and hardness, moisture retention, aspect and slope, and chemistry (e.g. the pH, mineral content, nutrient content, and salt content). Looking at trees, for example, not all deciduous trees are alike; and for a lichen some are more like a coniferous tree than a deciduous tree. For instance, Walewski shares that birch trees, although deciduous, often support communities of lichens expected on coniferous trees such as Camouflage Lichen (Melanelia). Similarly, Cedars, although coniferous, host lichens common on deciduous trees such as Speckled Shield Lichens (Punctelia).

.

.

Elevation: Rock-dwelling Lichens have been observed at extreme elevations. The Elegant Sunburst Lichen (Xanthoria elegans) was recorded by a Himilaya expedition in 1972 at an elevation of 7,000 m in the Karakorum. Granite-Speck Rim Lichen (Lecanora polytropa) was observed on the south side of Makalu at 7,400 m. To survive, lichens at these elevations must contend with extreme temperature fluctuations, high UV levels and wind speeds, variable snow cover, and short growing seasons. It’s no wonder that the Elegant Sunburst Lichen was exposed to space conditions and simulated Mars-analogue conditions in the lichen and fungi experiment (LIFE) in 2008 on the International Space Station (ISS).

.

.

Generalists vs Specialists

Some lichen are specialists (restricted to a single substrate type and specific condition such as pH). Their specific requirements compel them to occupy a narrow niche or life style and they are very successful in them. One example is tree lungwort (Lobaria pulmonaria), an acid-intolerant lichen that restricts itself to old-growth forests occupied by base-rich trees by depending on the undisturbed, pristine nature and complexity of these ancient ecosystems.

Other lichen are generalists (spreading themselves over wider habitat substrates and a wider range of conditions); these cosmopolitan ‘dilatants’ tend to be more common, given their less restrictive and more opportunistic lifestyle. The adaptive strategies of specialists and generalists differ accordingly.

But it seems that—just as a particular lichen can swap in or out its previous algal partner based on where it colonizes a rock cliff—a lichen’s overall lifestyle choice is not written in stone. Investigating trapelioid lichens on various substrates, Philipp Resi and colleagues discovered that the niche breadth (habitat preference and role) of any lichen could vary over time: specialists could evolve into generalists and back again, with transitions from generalism to specialism being more common than the reverse. This has, no doubt, a lot to do with what lichenologists are finding about lichens’ partner swapping, the hidden role of yeast and bacterial symbionts, and the subversive catalyst role of epigenetics.

.

.

Lichen Adaptations to Environmental Conditions

Lichens have several interesting morphological adaptations that help them survive the often extreme environments they inhabit and flourish in. These include adaptations to UV radiation, high wind, extreme temperature, low or highly fluctuating moisture and desiccation, and air pollution. These include:

Cortex: This fungal layer protects the algal layer from UV radiation in high elevations and exposed areas.

Crystals: These in the algal layer magnify light in shady habitats.

Anhydrobiosis: This is the ability of cells to survive dessication conditions through cell modification; along with vitrification, an antioxidant system and the ability to go dormant, this has allowed some lichen to survive space conditions for durations of up to 1.5 years (DeVera, 2012). Lichen can restore photosynthesis within minutes to an hour of rehydration.

Vitrification: This is the ability to convert algal symbionts to a glassy state to survive low water content.

Cavitation: This is the collapse of lichen fungal cells when dry.

Antioxidant system: a system that counteracts oxidative stress associated with wetting and drying cycles by entering a kind of suspended animation that can last for months to years.

Slow growth: The slow growth of lichen allows them to survive in harsh conditions.

Dormancy: This ability to shut down systems when conditions are too severe allows the lichen to ride out bad conditions and start up within minutes of resumption of good conditions.

Lichens produce more than a thousand chemical compounds (including secondary metabolites and pigments) that act as sunscreen, and help them fend off herbivores and insects, prevent freezing, reduce competition by other lichen, and stop seeds and spores from germinating in their soft, moist tissue.

Some secondary metabolites that have an allelopathic effect (e.g. reduces competition by inhibiting the growth of other lichen and plants) include orcinol (produced by Lecanora and Umbilicaria), protocetraric acid, atranorin, lecanoric acid, nortistic acid, usnic acids, and thamnolic acid. Some lichen allelopathic chemicals also act as antioxidants and insecticides, and are antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and antiparasitic–to name a few. This is likely why, even though lichen grow slowly, they remain resistant to decay microorganisms and are generally not eaten by generalist herbivores (excluding caribou and some specialists) and insects.

The most widespread pigment in lichens is usnic acid, which gives Usnea and Xanhoparmelia their characteristic pale yellowish-green or “usnic yellow” colour. Usnic acid acts like sunscreen against UV-B radiation. But it does so much more; this common secondary compound can also act as an antimicrobial agent, an antibiotic, antiviral, antimycotic, antiprotozoal, antiherbivoral, antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic agent. Xanthones add the yellow colour to Buellia halonia. Pulvinic acid colours species of Vulpicida, Letharia and Pleopsidium a brilliant yellow. And bright yellow, orange or red anthraquinones brighten Caloplaca, Xanthoria in orange-yellow and create the bright red fruiting bodies of British soldiers (Cladonia cristatella). Factors that affect colour expression in any individual lichen include age, exposure to sunlight, temperature and genetics, among others. Just as with aquatic algae, the photobiont of a lichen can be damaged by too much light, particularly UV light, so it uses pigments as ‘sunscreen.’ Lichens with the most intense colours are those most exposed to sunlight and lack of moisture. Presence of liquid water or vapour is also a key factor in colour expression.

.

.

Lichen Habitats

Given that most lichen are sedentary or sessile (like periphyton)—that is, once they settle, they stay put on a given substrate—the characteristic of the substrate or habitat becomes a useful diagnostic for identifying lichen. I’ve run across six habitat types in the literature that lichen grow on: rock, ground, bark, wood, leaves, and artificial substrates. Some lichen (the specialists) will restrict themselves on a particular substrate (like rock, for instance); others (the generalists) may grow on many types of substrates.

There is a seventh ‘habitat’ for some lichen, mostly those found in semi-arid to arid regions: air. Air lichen are itinerant wandering lichen, called by some ‘vagrant’ or ‘vagabond’ lichen, and likened by some to tumbleweed. The Tumbleweed Shield Lichen (Xanthoparmelia chlorochroa), abundant on the High Plains of Wyoming, exemplifies this itinerant lifestyle. It remains unfixed to any substrate and blows around in the wind from location to location. The fruticose Richardson’s Masonhalea Lichen (Masonhalea richardsonii) curls up when dry and spreads by the wind across the open northern tundra of Canada.

The Germans call these wandering lichen Wanderflechten. Purvis shares the story of how in 1829, during the war between Russia and Persia, a town on the Caspian Sea was suddenly covered by a lichen—Lecanora esculenta—which literally fell from heaven. It was made into bread and eaten by starving people. Sounds a bit like manna?…

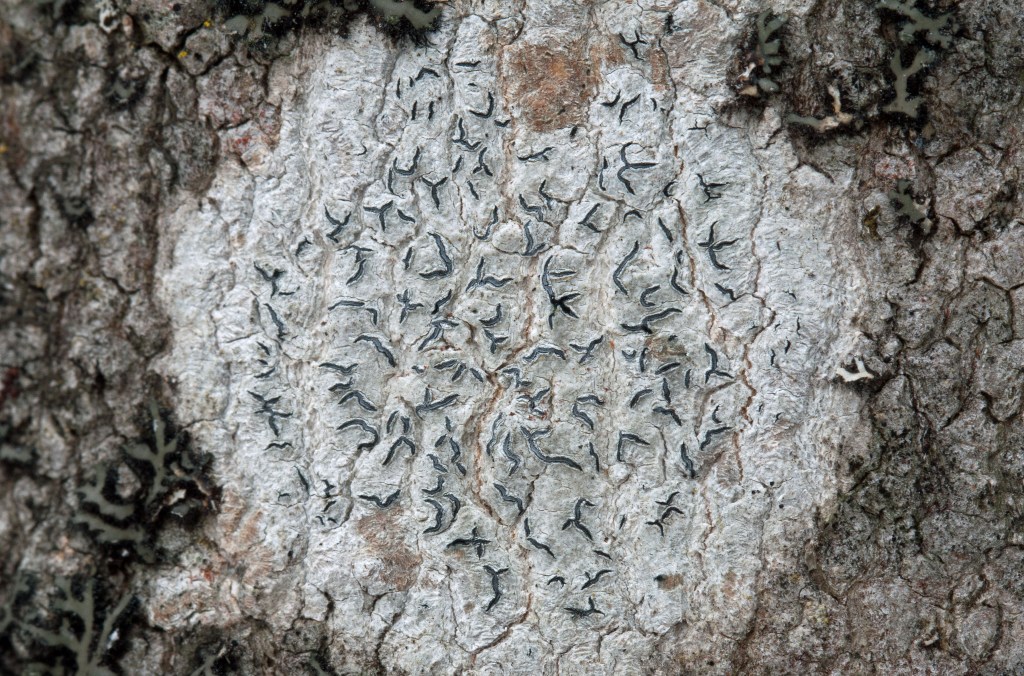

ROCK SUBSTRATES: Saxicolous Lichen

.

Saxicolous lichen colonize rocks, cliffs, talus, boulders, stones, pebbles, or like substances such as brick, cement and shingles. Saxicolous lichen are often found among the mosses that also colonize these same surfaces. Saxicolous lichens grow among the rock crystals, helping to break down surfaces for mosses and other colonizers. Crustose lichen tend to be the most abundant lichen on rock, often growing circularly outward; they can be divided into epilithic (living on the surface of the rock) and endolithic (living inside the rock). The type of rock—whether acidic (siliceous or quartz-rich rock such as granite) or basic (e.g. rocks with calcium carbonate such as limestone) supports different lichen. The bright-orange lichen Caloplaca tends to prefer limestone; while the yellow-green Map Lichen Rhizocarpon geographicum prefers siliceous rock. Runoff from these rocks and surfaces will also affect the lichen growing beneath them.

Check out my article “The Lichen Forest of Catch Rock” for more examples of saxicolous lichen on an acidic siliceous granite outcrop in the Canadian Shield.

.

GROUND SUBSTRATES: Terricolous Lichen

.

Terricolous lichen colonize ground that includes soil, moss, detritus and decaying trees. The hyphae produced by terricolous lichen help stabilize and fertilize the soil with organic matter and nitrogen. Lichen that are light-coloured help keep the soil cool and moist by reflecting heat. They also trap dust and act as substrates for other living things. Reindeer Lichens (Cladonia rangifolia, C. mitis, and C. stellaris) play a critical role in the survival of boreal and arctic ecosystems and is a staple of many northern wildlife, particularly as winter forage for caribou.

Along with mosses, liverworts, cyanobacteria, algae, fungi and bacteria, ground lichen help form a crypogamic crust; this is a soil crust that dominates large areas of North America and other parts of the world; it significantly helps in carbon sequestration, provides nutrients, and stabilize the soil, preventing erosion.

TREE SUBSTRATES: Corticolous (on Bark) and Lignicolous (on wood) Lichen

.

Corticolous lichen colonize bark of tree trunks, branches, and twigs. Check out my article “Living Bark of a Maple” for examples of corticolous lichen on a maple tree. Lignicolous Lichen colonize exposed wood. Check out my article “Life on a Fencepost” for examples of lignicolous lichen. Tanunchai et al. argue that factors including tree species, tree type, water content, pH and location help shape the diversity and community composition patterns of lichen.

Lichen that grow on conifers and deciduous trees differ based on their surface textures, chemistry, light and moisture. Conifer bark, for instance, is rich in organic resins and gums, and is acidic. The canopy of a conifer is also more dense than most deciduous trees; this prevents some light from penetrating to the trunk. The sloping nature of spruce and fir trees also allows rain to fall to the forest floor rather than run down the trunk as it readily does on a deciduous tree. Anyone caught in a rainstorm, like me, will vouch for this difference. The pH and water absorbency of bark will affect lichen colonization and growth. Walewski tells us that, “Elm and poplar bark are low in acidity, stable and fairly absorbent. Oak, hickory and linden have hard, rough, acidic bark and host different [lichen]. Beech and other trees with smooth, living, green bark are home to yet another community of lichens.”

.

.

According to the British Lichen Society, the most acid barked trees are larch and pines (down to pH 3.2), then in order of reducing acidity birch, oak (pH 3.8-5.8), rowan, alder, beech, lime, ash (pH 5.2-6.6), elder, sycamore and field maple, apple, poplar, willow and elm (pH 4.7-7.1). Bark pH is also affected by pollution, and may vary at different heights in the tree. The society adds that some lichens restrict themselves to ancient forests, where ecological continuity over hundreds of years has been maintained.

.

.

As trees age, so does their bark. The bark of a sugar maple, for instance, is smooth when the tree is young; with age it softens, cracks and forms furrows that ooze alkaline nitrogenous compounds. Walewski tells us that older trees have a greater diversity of lichens. Walewski notes that, while the Hoary Rosette Lichen (Physcia aipolia) increases up the trunk of a tree, the Hooded Rosette Lichen (Physcia adscendens) decreases in abundance. This may have something to do with light conditions or more likely nutrient conditions of the tree. The British Lichen Society mentions that Physcia adscendens is very common on nutrient enriched tree bark, often forming luxuriant colonies along rain tracks on tree trunks. Its preference for lower older bark likely relates to how older cracked bark leaches out alkaline nitrogenous compounds.

.

LEAF/NEEDLE SUBSTRATES: Foliicolous Lichen

These lichen colonize leaves and needles of trees and shrubs. Tanunchai et al. determined that P. adscendens often dominated the foliicolous lichen growing on the leaves and needles of 12 temperate tree species they studied. They also detected algae and cyanobaceria—potential photobionts—colonizing these leaves and needles. Purvis writes that in the understory of rain forests in Costa Rica, up to 300 species of lichen live on leaves at a single site. The laurel Ocotea atirrensis was found to support 50-80 different lichen species on a single leaf.

.

Artificial SUBSTRATES

.

These include artificial substrates such as glass, plastic, metal such as iron, old leather, rubber tires, rusting cars, asbestos, and fibrolite roofing materials. New Zealand Plant Conservation Network reported that the shadow lichen Phaeophyscia orbicularis colonized many of these artificial substrates.

.

Outer Space & Mars?

In 2002, De Vera and their research team showed that the sunburst lichen Xanthoria elegans and the lichen Fulgensia bracteata along with their isolated photobionts and mycobionts withstood outer space conditions that included vacuum and ultraviolet radiation. Three years later the European Space Agency took a specimen into space and exposed it for two weeks. When it returned, it was ok and could photosynthesis, grow and reproduce.

.

.

.

Glossary:

Cryptogam: a non-flowering plant or plant-like organism that reproduces through spores, such thallophytes (lichen, fungi, slimemolds, and algae), bryophytes (e.g. liverworts, hornworts & mosses) and pteridophytes (e.g. ferns and allies).

Cryptogamic crust: also known as biocrust, is a crust of top soil helps hold loose soil together and prevents erosion; it consists of microscopic non-vascular assemblages of blue-green algae, diatoms, golden brown algae, lichens, mosses and some liverworts.

.

.

.

References:

Backer et. al. 2023. “Allelopathic effects of three lichen secondary metabolites on cultures of aposymbioticlly grown lichen photobionts and free-living alga Scenedesmus quadricauda.” South African J. Bot. 167: 688-693.

Brandt et. al. 2015. “Viability of the lichen Xanthoria elegans and its symbionts after 18 months of space exposure and simulated Mars conditions on the ISS.” International Journal of Astrobiology.

De Vera, J.O., G. Horneck, P. Rettberg. 2002. “The potential of the lichen symbiosis to cope with extreme conditions of outer space—1. Influence of UV radiation and space vacuum on the vitality of lichen symbiosis.” International Journal of Astrobiology 1(4): 285-293.

De Vries, Bernard, Irma de Vries. 2006. “Getting to Know Your Boreal Lichens of Saskatchewan, Canada.” Series II. Saskatchewan Environment, Conservation Data Centre, Resource Stewardship Branch.

Eldridge DJ, Greene RSB. 1994. “Microbiotic soil crusts: a review of their roles in soil and ecological processes in the rangelands of Australia.” Australian Journal of Soil Research 32:389–415.

Galloway D.J. 1985: Flora of New Zealand: Lichens. Wellington: PD Hasselberg, Government Printer. 662 pp.

Galloway D.J. 2007: Flora of New Zealand: Lichens, including lichen-forming and lichenicolous fungi. 2nd edition. Lincoln, Manaaki Whenua Press. 2261 pp.

Hale, Mason E. 1967. “The Biology of Lichens.” Edward Arnold Ltd., London. 176pp.

Hawksworth, David L. and Francis Rose. 1977. “Lichens as Pollution Monitors” Edward Arnold Ltd., London. 60pp

Heim, Amy and Jeremy Lundholm. 2014. “Cladonia lichens on extensive green roofs: evapotranspiration, substrate temperature, and albedo.” F100Res. 23(2): 274.

Joly, K. and M. D. Cameron. 2018. “Early fall and late winter diets of migratory caribou in northwest Alaska.” Rangifer 38(1):27-38.

Kramer, et al. 2005. “Antioxidants and photoprotection in a lichen as compared with its isolated symbiotic partners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102(8): 3141-3146.

Lowry, James D. 1986. “Biological Role of Lichen Substances.” The Bryologist 89(2): 111-122.

Liška, Jiří; Herben, Tomáš. 2008. “Long-term changes of epiphytic lichen species composition over landscape gradients: an 18 year time series”. The Lichenologist. 40(5): 437-448

McCune, B. 2000. “Lichen communities as indicators of forest health.” The Bryologist 103(2): 353-356.

McMullin, R. Troy. 2023. “Lichens: The Macrolichens of Ontario and the Great Lakes Region of the United States.” Firefly Books Ltd., Richmond Hill, ON. 607pp.

Perlmutter, G.B. 2010. Bioassessing air pollution effects with epiphytic lichens in Raleigh, North Carolina, U.S.A. The Bryologist 113(1): 39-50.

Purvis, William. 2000. “Lichens.” Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. 112pp.

Resi, Philipp, Fernando Fernández-Mendoza, Helmut Mayrhofer, and Toby Spribille. 2018. “The evolution of fungal substrate specificity in a widespread group of crustose lichens.” Proc. Biol. Sci 17: 285.

Spribille, Toby, Philipp Resi, Daniel E. Stanton, Gulnara Tagirdzhanova. 2022. “Evolutionary biology of lichen symbioses.” New Phytologist 234(5): 1537-1902.

Tanunchai, Benjawan, et.al. 2022. “More than you can see: Unraveling the ecology and biodiversity of lichenized fungi associated with leaves and needles of 12 temperate tree species using high-throughput sequencing.” Front Microbiol. 16(13):1-17.

Walewski, Joe. 2007. “Lichens of the North Woods.” Kollath & Stensaas Publishing, Duluth, MN. 152pp.

.

.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.