When I discovered that The Guardian was hosting a celebration of The Invertebrate of the Year, I was both fascinated and intrigued. This is their second year of what is becoming an annual vote by Guardian readers. Last year the common earth worm won hands down.

Why host such an event?

On the Guardian’s Science Weekly Podcast, Madeleine Finlay and Patrick Barkham discuss why we need to pay attention to these creatures and why they are important. Patrick tells us that, “These are ecosystem engineers, they’re pollinators, they’re soil creators, fertility makers, ocean cleaners; they’re crucial animals.”

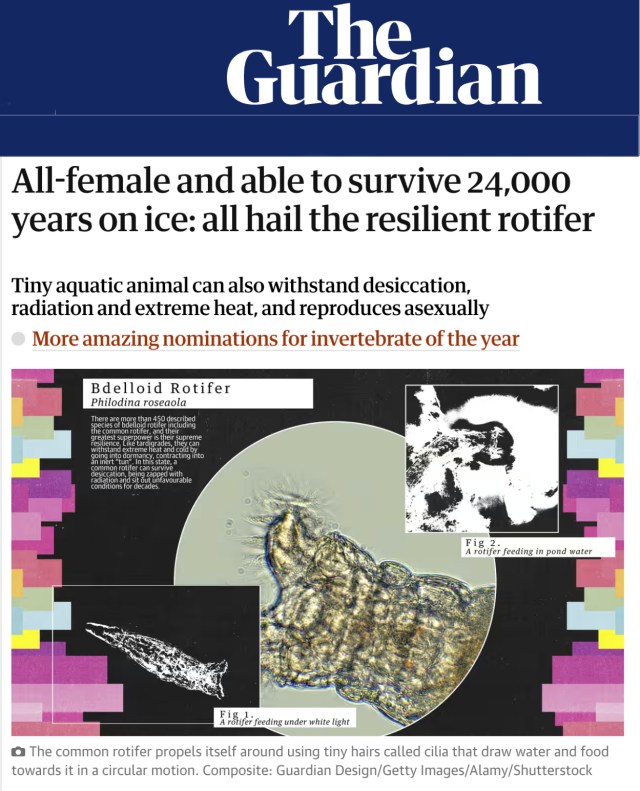

Thinking this would be fun, I put in my candidate. I nominated the common Bdelloid rotifer, an all-female rotifer that has survived for millennia without sex. I made such a convincing case that the bdelloid rotifer was selected one of the top ten from over two thousand nominations. Not bad for such a tiny beast.

.

.

Patrick Barkham wrote: “The Canadian limnologist, science fiction writer and Guardian reader Nina Munteanu makes a brilliant case for the common rotifer in her nomination for invertebrate of the year 2025: ‘Highly variable environments tend to support organisms uniquely equipped for change,’ she says. ‘These are the explorers, misfits, and revolutionaries who do their work to usher in a new paradigm. They carry change inside them, through phenotypic plasticity, physiological stress response mechanisms, and life history adaptations.’ ”

On the Guardian Science Weekly Podcast, Patrick Barkham tells Madeleine Finlay why these tiny creatures deserve more recognition and I was one of three readers who made my case for my favourite.

“Invertebrates don’t get the attention lavished on cute pets or apex predators,” said Barkham. “But these unsung heroes are some of the most impressive and resilient creatures on the planet. So when the Guardian opened its poll to find the world’s finest invertebrate, readers got in touch in droves. A dazzling array of nominations have flown in for insects, arachnids, snails, crustaceans, corals and many more obscure creatures.”

Here’s what I said: “Most people don’t see them or even know they exist, but these badass all-female rotifers have thrived in highly variable environments for over 40 million years. They’ve survived extreme conditions and major climate change phenomena. They lurk in places no one else can handle, like temporary ponds, moss, even tree bark. If their pond dries up, they go dormant and basically dry up waiting for a wet day to rehydrate and go on living. They don’t bother with sex (it’s too slow to find partners); instead they clone themselves and rely on DNA repair and gene transfer to adapt to their changing environment. The thing that totally fascinated me about these simple rotifers is how they count on change for strength: Bdelloid mothers that go through desiccation and dormancy produce daughters with increased fitness and longevity. If desiccation doesn’t occur over several generations, the rotifers lose their fitness. They need the unpredictable environment to keep robust.”

Madeleine mentioned that, “these tiny invertebrates can tell us so much about the world around us.” Patrick agreed: “this seems to be resonating with people… lots of people at the moment seem drawn to tiny but very resilient animals and in times of geopolitical instability and climatic extremes … we feel very powerless and small ourselves, but we draw comfort from the survival of the tiny animals.” He added that a bdelloid rotifer was recently found in a frozen river in Siberia and thawed and it returned to life and reproduced asexually after being frozen for 24,000 years. “It gives us real hope that life on Earth is going to flourish and endure despite whatever we inflict upon it in the Anthropocene and this sixth great extinction that we are the authors of.”

.

.

“They really bring this message of survival and in that sense there’s hope,” said Madeleine. Patrick added that the selection of the final ten was based on a wish to show the diversity of the wondrous life in the world… “We wouldn’t last long without many of these invertebrates, pollinating our food supplies and giving fertility to our soil … but… it’s a moral question, really, that these animals have a right to live and that’s why we must live more gently on the Earth.”

To hear me make my case for the bdelloid rotifer to Nil and Chris on CBC’s “As It Happens”, go to the link and scroll to minute 18:05.

.

.

The rotifer wasn’t voted the invertebrate of the year; that nod was given to the tardigrade, another microscopic superhero. You can find out more about the tardigrade on my posts A Tardigrade Christmas and When Water Bears Inspire Industry. The bdelloid rotifer made it to the top ten; she got her recognition, and that’s really what counts.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.