A lichen is a collaborative association of two organisms to survive, often in harsh environments like exposed rocks or cold deserts. One partner—the photobiont—is a photosynthetic cyanobacterium or alga, or both; they form food from carbon dioxide. The other partner—the mycobiont—is a fungus, which provides moisture, nutrients, and protection for the consortium.

.

Lichens have recently been defined as self-sustaining ‘micro-ecosystems’ (see Insarova and Blagoveschenskaya, 2016; Hawksworth and Grube, 2020). This symbiotic association is ultimately a marriage wherein both partners are better for the association than without it. The algal partner is the primary producer, supplying the fungal partner with carbohydrate products of photosynthesis to sustain the association. Cyanobacterial partners additionally fix nitrogen from the air. In turn, the fungal partner provides structural protection and additional nutritional needs. Surrounding fungal tissues and their secondary metabolites also protect the lichenized alga from desiccation, photoinhibition, temperature extremes and herbivory. All to say that the symbiotic association significantly expands the ecological range and abundance of either partner alone.

Lichenologists tell you that fungi (mycobiont) make up the majority of the lichen consortium (around 80% of a given lichen); its photosynthetic algal partner (photobiont) usually trails at close to 20%, shared with yeast and bacteria. The lichenologists also say that every lichen has a unique single fungus that, as the dominant partner, gives the lichen its shape and fruiting bodies. For this reason, a lichen is named after the fungal partner.

While the fungus may determine the name of the lichen, the alga (or algae) plays an important role in determining its character. They’re just quiet about it. Like shy introverts, they hide beneath the boisterous and expressive fungal ‘blanket’; invisible when it’s dry and only showing their colours when the rains have chased away the crowds.

.

The common lichen Physcia biziana, shown below and to your left, is a dull blue-grey when dry, but when a little moisture finds it, this lichen quickly transforms into a beautiful sea-green colour, its maculae showing more markedly against the vibrant colour of the photosynthetic partner. I once did an experiment using a dry twig with abundant Physcia growing on it; I dunked the twig into the river water and within five minutes, the dull grey had turned to vibrant green!

.

Dry lichen are most often grey or tan (if not coloured by secondary pigments such as the yellow-orange pigment parietin of Xanthoria fallax, which turns green when wet from bright yellow-orange when dry.)

When moist, the fungal cells of the cortex become transparent, revealing the green-coloured photosynthetic partner, now activated by the moisture, and making the lichen appear more vibrant and colourful.

Photobionts (Algal / Cyanobacterial Partners)

Only a few kinds of photosynthesizing partners are found in lichens—mostly green algae and cyanobacteria. In some rare cases, they can even be the dominant partner (e.g. jelly lichens such as Collema spp. and Leptogium spp.). But most of the time, they’re unseen, diligently making sugars in the ‘kitchen.’ Dorset Nature provides a comprehensive set of microscopic images of the most common photobionts in lichens.

.

.

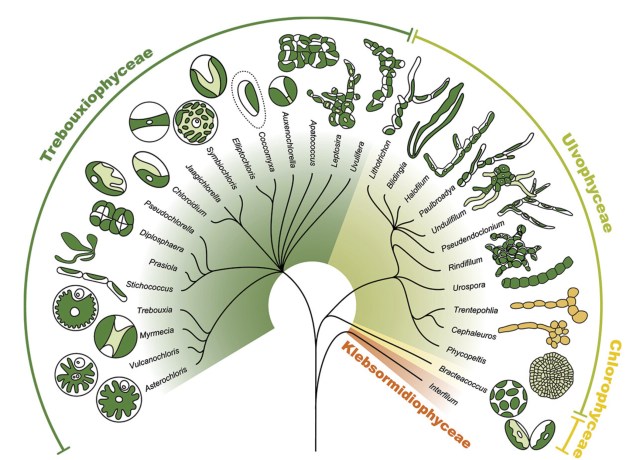

About 90% of lichens have a green alga (Chlorophyta) as the photobiont, providing sugars from carbon dioxide. The most frequent are the genera Trebouxia, and other chloroccocoid algae Myrmecia, Dictochloropsis, and Asterochloris. The alga Trebouxia is found in close to half the lichens studied so far.

.

.

The bright green wandering form of the alga Trebouxia (out of its symbiotic lichen ‘cage’) can be seen in my photo below of the wet form of Bitter Wart Lichen. I’ve also seen Trebouxia bursting out of several leprose lichens (e.g. Lecanora symicta and Lecanora allophana). According to Veselá and colleagues this is a common sight with leprose lichens as their apothecia break open during periods of high moisture to release their spores. According to Sanders & Masumoto photobionts continually escape from lichen thalli through various means such as soredia, isidia, thallus fragments, co-dispersed hymenial, epithecial or conidiomal algae. And these provide opportunities to develop free-forms, independent of their partnership inside the lichen assemblage. As with many other lichan algal partners it seems, Trebouxia does not require lichenization to survive; it can survive outside of the lichen symbiosis, as a free-living organism, either alone or in colonies. According to Sanders & Masumoto (2021), many lichen algal partners are facultative photobionts, with the ability to live and thrive outside their lichen association and independent of the mycobiont.

.

.

Sanders & Masumoto argue that the fungal partner, with its elaborate structural adaptations for algal cultivation, its more fully committed to symbiosis than its algal partner: “The mycobiont frees itself of symbiosis only in spore dispersal, seeking algal partners again immediately upon germination. To carry out sexual reproduction, it must be in symbiosis, whereas its photobiont appears to need aposymbiotic freedom to do so. From the alga’s point of view, whenever unfavourable conditions reduce its possibilities of aposymbiotic success, the benefits of lichenization may begin to outweigh any disadvantages. Photobionts may rely on lichen symbioses for long-term persistence in habitats periodically subject to adverse conditions, while needing intervals of independence under favourable conditions to complete their life cycles. Thus, mycobiont and photobiont life histories do not fully coincide, but produce a lichen where they intersect compatibly.” Natural selection, they argue, has optimized the mycobiont for symbiosis; while the photobiont has adapted to swing naturally from autonomy to symbiosis.

.

.

Also common is the orange-pigmented genus Trentepohlia (also a green alga), which is found in the ‘secret writing’ crustose lichen Graphis scripta, and responsible in its free unlichenized form for the red painted look on many deciduous and coniferous trees called the Red Bark Phenomenon.

.

.

Lichens also have cyanobacteria as their photobiont; aside from photosynthesizing sugars, the cyanobacteria can also fix nitrogen from the air for the lichen community. Cyanobacteria that occur in lichen include Nostoc, Scytonema, and Gloeocapsa. Check out my article on Nostoc commune (a Nostoc species found in lichen), to get an appreciation for the versatile lifestyle of this clever genus. Ulla Kaasalainen and colleagues tell us that Nostoc occurs in a wide variety of cyanolichens, either as the primary photobiont (in bipartite lichens) or as accessory photobiont together with green algae (in tripartite lichens). They are common in Peltigeralean lichens such as Peltigera, Collema, and Leptogium.

.

.

Some lichen have both algae and cyanobacteria in their thallus. In most cases, the main photosynthesizing photobiont is the green alga; the nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria are localized in distinct structures called cephalodia.

According to lichenologist William Purvis, most lichen fungi are highly selective, forming associations with singularly compatible photobiont species. However, notable exceptions are worth discussing:

- The same lichen (and its mycobiont) may contain different photobionts in different geographic locations

- Another fungus growing on the lichen (called lichenicolous fungi) may share the alga of its host lichen and later swap it for another species it finds (e.g. Diploschistes muscorum growing on Cladonia spp.)

The same lichen can exist in several very different forms, depending on the photobiont it contains; these different forms of the same lichen are called photomorphs. This is where the ‘character building’ comes in…

.

Photomorphs

It was only recently that lichenologists discovered that lichen algae (photobionts) play a definitive role in determining what lichen look like. Jack R. Laundon coined the term photomorph in 1995 as a unique identifier of phenotypically different lichens (with the same mycobiont but different photobionts). Laundon defined a photomorph “as an organism whose form is determined by the nature of its photosynthesis.” Two years later, Heidmarsson et al. confirmed the use of the term, calling attention to the fact that lichen ‘individuals’ are really “lichenized ecosystems.”

.

.

Purvis writes about the work of British Lichenologist Peter James in sheltered gorges of New Zealand; here he discovered that the different looking lobes of a certain lichen belonged to different photobiont species. For instance, he found that the leafy lichen Sticta felix (which contained green algae) grew out of the shrubby Dendriscolaulon (which contained cyanobacteria). He also found separate individuals of both lichens and realized that environmental factors, such as light and humidity, determined which photobiont was present in the lichen. Purvis reminds us that because all lichen names are based on the fungus present, a single name needed to be used for what were previously considered to be two lichens.

.

.

Purvis tells us that there are many examples of algal switching, particularly in the foliate lichen, such as Nephroma, Sticta and Lobaria. In these groups, the same fungus may be associated with either a green alga and appear leaf-like or with a cyanobacterium and often looking shrub-like or as tiny granules. The different photobionts can either occur together in the same thallus (possibly in different parts of the thallus) or separately. Purvis gives the example of Sticta canariensis in the Cloud forest in the Azores archipelago of Portugal, where variations in morphology, distribution and chemistry are so striking to suggest two different species.

.

.

Why these striking differences occur because of different photobionts remains unclear. However, lichenologists have recently suggested that this is because the fungus builds itself around the algal or cyanobacterial partner to maximize efficient use of its resource. The mycobiont shapes its structure to optimize the capture of light and nutrients by its symbiotic photosynthesizing partner. Different photobiont species have varying photosynthetic rates, cell sizes, and growth patterns; these influence how the fungal hyphae arrange themselves to optimize symbiosis. The ecological implications lie in the ability of a particular lichen to occupy a wider range of habitats and adapt to different environmental conditions by selecting, stealing, and swapping partners. I’m reminded of the ancient all-female bdelloid rotifer, which has thrived for millennia: adapting to a changing environment by swapping necessary genetic material through anhydrobiosis, horizontal gene transfer, DNA repair and use of mobile DNA, and other epigenetic mechanisms.

In 2020, Moya and colleagues wrote that “photobiont switching is a ubiquitous phenomenon in lichens and appears to play a vital role in lichen adaptation to environmental conditions. Association with a wide range of symbionts may help lichens survive under harsh environmental conditions.”

.

Lichenicolous Lichen & Partner Swapping

I recently read a journal paper by Nimis and colleagues about lichenicolous lichen that regularly start their life-cycle on the thalli of other lichen species, eventually building their own lichenized thallus. My first thought was of the mother tree, feeding her saplings through mycorrhizal connections underground.

I also read about some shady dealings like ‘algal stealing’ and ‘algal switching’ by lichenizing fungi (lichenicolous mycobiont) ‘parasitizing’ lichen. The fungus originally settles on the host lichen and takes a few algal cells from the host (without detriment to it) to develop its own symbiosis; it grows further using the thallus host as substrate but derives its nutrients from its own photobionts. At this point it has become a lichenicolous lichen. According to Nimis and colleagues, the fungus takes over the photobiont of the host lichen to avoid the need to search for a new photobiont of their own—admittedly a perilous and arduous endeavour in a variable environment. Once the photobiont has been acquired, it is maintained or substituted with a different and more favourable algal partner through algal switching (see the paper by Friedl).

The photosynthetic partners—like 20th century wives—may appear the passive coin tossed around by scheming fungi; but they wield much more power than meets the eye. A power of subtle authority and wily influence. And ultimately the power of sovereignty: that they virtually all can live without the partnership—and do. And thrive in doing so.

For an example of this remarkable self-sufficiency, see my article on the Red Bark Phenomenon.

.

.

References:

De Carolis, Roberto, et.al. 2022. “Photobiont Diversity in Lichen Symbioses From Extreme Environments.” Front Microbiol 29(13):809804.

Diederich P., JD Lawrey and D. Ertz. 2018. “The 2018 classification and checklist of lichenicolous fungi, with 2000 non-lichenized, obligately lichenicolous taxa.” The Bryologist 12(3): 340-425.

Friedl, T. 1987. “Thallus development and phycobionts of the parasitic lichen Diploschistes muscorum.” Lichenologist 19(2): 183-191.

Hawksworth D. and M. Grube. 2020. “Lichens redefined as complex ecosystems.” The New Phytologist 227(5): 1281-1283.

Heidmarsson, Starri, Jan-Eric Mattsson, Roland Moberg, Anders Nordin, Rolf Santesson & Leif Tibell. 1997. “Classification of lichen photomorphs.” Taxon 46: 519-520.

Honegger, R. 1991. “Functional aspects of the lichen symbiosis.” Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 42, 553–578.

Insarova ID. and EY. Blagoveschchenskaya. 2016. “Lichen Symbiosis: Search and Recognition of Partners.” Biology Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences 43(5): 408-418.

Kaasalainen, Ulla. David P. Fewer, Jouni Jokela, Matti Wahlsten, Kaarina Sivonen, and Jouko Rikkinen. 2013. “Lichen species identity and diversity of cyanobacterial toxins in symbiosis.” New Phytologist 198(3): 647-651.

Laundon, Jack R. 1995. “On the classification of lichen photomorphs.” Taxon 44: 387-389.

Moya, P. A. Molins, S. Chiva, J. Bastida, and E. Barreno. 2020. “Symbiotic microalgal diversity within lichenicolous lichens and crustose hosts on Iberian Peninsula gypsum biocrusts.” Scientific Reports 10(1): 14060.

Nimis, Pier Luigi, Elena Pittao, Monica Caramia, Piero Pitacco, Stefano Martellos, and Lucia Muggia. 2024. “The ecology of lichenicolous lichens: a case-study in Italy.” MycoKeys 105: 253-266.

Purvis, William. 2000. “Lichens.” Natural History Museum, London. 112pp.

Richardson, DHS. 1999. “War in the world of lichens: Parasitism and symbiosis as exemplified by lichens and lichenicolous fungi.” Mycological Research 103(6): 641-650.

Sanders W.B. & Masumoto H. 2021. “Lichen algae: the photosynthetic partners in lichen symbioses.” The Lichenologist 53: 347–393.

Veselá, Veronika, Veronica Malavasi & Pavel Skaloud. 2024. “A synopsis of green-algal lichen symbionts with an emphasis on their free-living lifestyle.” Phycologia 63(3): 317-338.

.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

.

2 thoughts on “The Character of a Lichen: Algae—Wizard Behind the Curtain or Kept Wife?”