Big lichen have little lichen upon their backs to mine them, and little lichen have lesser lichen, and so ad infinitum.

Adapted from Augustus DeMorgan

.

It was recently—in the past year—that I rekindled my interest in lichens and started studying them in earnest. I purchased some excellent keys, went to the library and perused textbooks, read scientific papers on lichen ecology, taxonomy and the strange habits of these recognized miniature self-sustaining ecosystems of fungi, algae, yeast and bacteria. I learned that lichens are named after their fungal (mycobiont) partner; they grow just about everywhere and have been categorized by their morphology into three main forms: crustose (forming a thin crust or film); foliose (leaf-like); and fruticose (more shrub-like). I learned that they are also categorized by the substrate they colonize. For instance, I learned that a terricolous lichen lives on the ground; a corticolous lichen is one that colonizes bark; a lignicolous lichen settles on wood; and a saxicolous lichen prefers rock or artificial substrates like concrete to live on. There are even foliicolous lichen that live on or in leaves. Some lichen are opportunistic generalists that don’t care where they live, showing a wide niche breadth and therefore found on many types of substrates; other lichens, like picky eaters, can be defined by their very narrow substrate specificity. For instance, Xylographa opegraphella only grows on driftwood. Resl and colleagues have shown that some generalists can become specialists and vice versa.

.

.

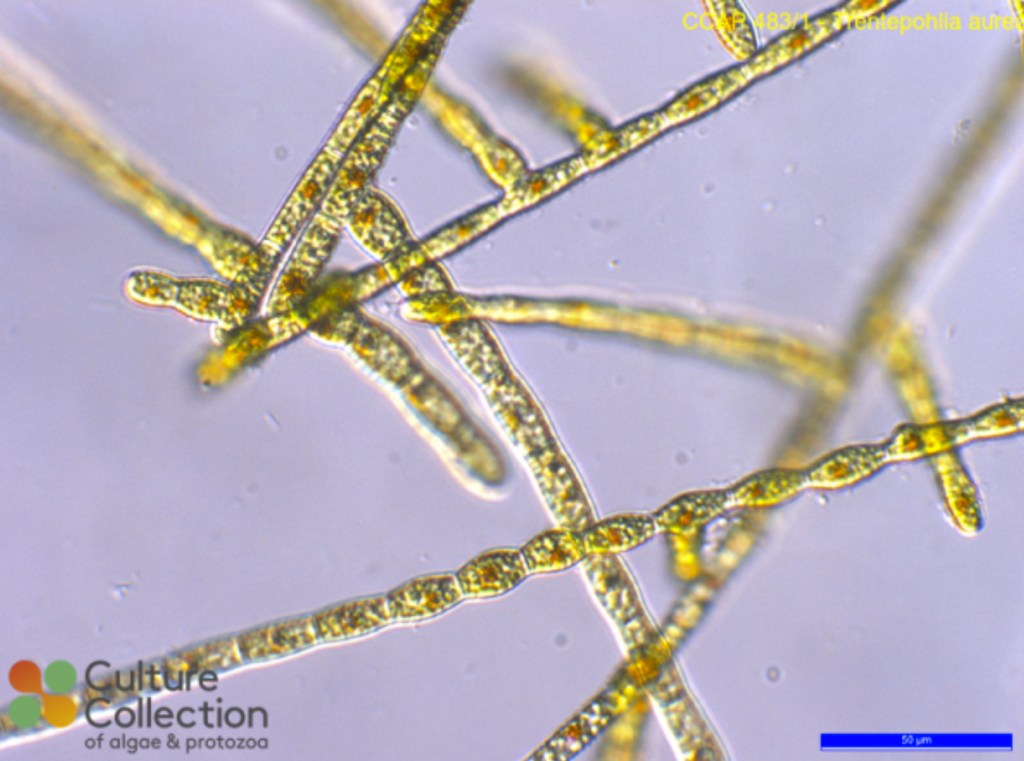

And then there are the lichenicolous lichen. I stumbled on this last category of lichens when I discovered the script lichens. Script lichens are crustose lichen with dark squiggly, often branching fruiting bodies (apothecia) that resemble cryptic scrawls and symbols (possibly by wood sprites). I’d come across and identified the Common Script Lichen (Graphis scripta) colonizing a beech tree in an old-growth hemlock forest near Peterborough, Ontario. This lichen contains the photobiont Trentepohlia, a green filamentous alga also responsible for The Red Bark Phenomenon in its free form and with preference for shaded-humid and warm conditions.

.

In researching Graphis scripta, I discovered many other lichens in the Graphis genus and the Script Lichen family. Among them were lichen growing on lichen. These are called lichenicolous lichen. And one such lichen typically grows on Graphis scripta.

.

Arthonia graphidicola is a lichen without a thallus whose apothecia, which resemble G. scripta apothecia, colonize the host thallus then erupt through the host’s thallus—somewhat like the alien in Alien, though without the devastating mess left behind (as in a dead eviscerated human). The apothecia of A. graphidicola, which appear as rounded, many-sided, or elongated structures, are difficult to distinguish from the host’s own apothecia. Some researchers suggest that the apothecia of A. graphidicola are smaller and less elongated or elaborate as those of G. scripta (check out the image below for comparison). This lichenicolous lichen may also show its presence by staining the thallus of its host pink. I recall witnessing that phenomenon before I learned about this interesting tell.

A lichenicolous lichen is basically a lichen that grows on or in another lichen; a lichen that starts its life-cycle on the thallus of other lichens, eventually building its own lichenized thallus. Some are specialists (growing only on certain species of lichen); others are generalists, able to grow on several lichen species.

Diederich et al. (2018) estimated over 2,000 species of lichenicolous fungi worldwide—many that evolve into lichen once they colonize a host—known to live on lichens as host-specific parasites, pathogens, saprotrophs and commensals. Lichenicolous lichens are considered a subset of this group with a few hundred species recognized so far. According to Knudsen (2013) lichenicolous lichen have a two-stage cycle. Many start as juvenile non-lichenized fungal parasites which then develop into a lichen by stealing an algal partner from the host lichen.

‘Parasitic lichens’ are turning out to be more common than once believed; this emerging science reads like a chapter on corporate intrigue with anything from aggressive mergers and asset stealing to hostile takeovers.

.

In 1980, David Hawksworth and colleagues described how a lichen fungus invaded a lichen thallus to take over the Trentepohlia photobiont of a host lichen and form its own morphologically distinct thallus. In 1987, Thomas Friedl studied the lichenicolous lichen Diploschistes muscorum that parasitizes the squamules of various Cladonia species, developing apothecia in the Cladonia squamules and associating with the photobiont Trebouxia irregularis. As the Cladonia increasingly disintegrated, D. muscorum swapped T. irregularis for T. showmanii, a more suitable photobiont with which it became independent.

In 2020, Moya and colleagues looked at several lichenicolous lichens growing on gypsum biocrusts and showed that lichenicolous lichen take advantage of the microalgae available in the host’s thallus, avoiding wasting energy to find an appropriate algal partner in the substrate. Acarospora spp. parasitized Diploschistes diacapsis in its first growth stage as the host lichen donated its algae to the lichenicolous lichen, which became independent when mature, often through algal swapping. According to the researchers, “photobiont switching is a ubiquitous phenomenon in lichens and appears to play a vital role in lichen adaptation to environmental conditions. Association with a wide range of symbionts may help lichens survive under harsh environmental conditions.”

.

.

Nimis and colleagues (2024) suggest that at least some lichenicolous lichen are not true “parasites”, as they are often called, but gather their algal partners (photobionts), which have already adapted to local ecological conditions, from their hosts, and eventually develop an independent thallus. The researchers also suggest that the lifestyle of lichenicolous lichens is one of mostly sexual reproduction, a crustose growth-form, and a higher incidence of a green, non-trentepohlioid photobiont (recall that Graphis scripta has the green alga Trentepohlia as its photobiont). Trentepohlia prefers shaded-humid and warm conditions (where it often occurs in its free state). The lack of free-living algae, particularly in dry areas, may explain why many lichenicolous fungi/lichen start off as “algal thieves.” Many start by initially ‘stealing’ photobiont cells from the host thallus to make their own and develop their own symbiosis while continuing to use the thallus of the host as substrate. It’s a clever shortcut to save energy and resources, particularly in more extreme and harsh resource-poor environments.

.

Who’d have thought that these unassuming sedentary lichens were Nature’s wiley types and so adventurous…

.

References:

Deiderich, P., JD. Lawrey, and D. Ertz. 2018. “The 2018 classification and checklist of lichenicolous fungi with 2000 non-lichenized, obligately lichenicolous taxa.” The Bryologist 121(3): 340-425.

Friedl, T. 1987. “Thallus development and phycobionts of the parasitic lichen Diploschistes muscorum.” Lichenologist 19(2): 183-191.

Hawksworth, D.L., B.J. Coppins, and P.W. James. 1980. “Blarneya, a lichenized hyphomycete from southern Ireland.” Bot J Linn Soc 79: 357-367.

Hawksworth, D. L. 1982. “Secondary fungi in lichen symbioses: parasites, saprophytes and parasymbionts.” J Harroti bot Lab 52: 357-366.

Knudsen, Kerry, John W. Sheard, Jana Kocourkova, and Helmut Mayrhofer. 2013. “A new lichenicolous lichen from Europe and western North America in the genus Dimelaena (Physciaceae).” The Bryologist 116(3): 257-262.

Moya, P. A. Molins, S. Chiva, J. Bastida, and E. Barreno. 2020. “Symbiotic microalgal diversity within lichenicolous lichens and crustose hosts on Iberian Peninsula gypsum biocrusts.” Scientific Reports 10(1): 14060.

Nimis, Pier Luigi, Elena Pittao, Monica Caramia, Piero Pitacco, Stefano Martellos, and Lucia Muggia. 2024. “The ecology of lichenicolous lichens: a case-study in Italy.” MycoKeys 105: 253-266.

Purvis, William. 2000. “Lichens.” Natural History Museum, London. 112pp.

Resl, Philipp, Fernando Fernandez-Mendoza, Helmut Mayrhofer, and Toby Spribille. 2018. “The evolution of fungal substrate specificity in a widespread group of crustose lichens.” Proc Biol Sci 17:285(1889).

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

One thought on “Lichen Ecology: Lichens that Grow on Lichens”