Lichens are badass shapeshifters. These unruly organisms that thrive in extreme environments and changing conditions grow everywhere. And most of us don’t even notice them.

Lichens can be found all over: from the plaster wall of an ancient church in England to a fence post on a rural road in Ontario to the leaves of a tropical rainforest of Costa Rica or inside a rock in the Antarctic. Eight to ten percent of terrestrial ecosystems are thought to be dominated by lichen. While some tell us that there are about 18,000 species of lichen inhabiting our planet, Lichenologist William Purvis suggests there are many more, possibly over 30,000. In the rainforests of British Columbia, Canada, 20 new species are added to the list every year.

This ubiquity and cosmopolitan nature of lichen can be attributed to their versatility and shapeshifting qualities, which includes a vagrant lifestyle for some (aka tumbleweeds) and incredible diversity in shape, texture and colour—even within the same lichen organism. Much of this ability lies in their structure: a symbiotic assembly of at least two organisms, a protective fungus and sugar-creating alga and/or cyanobacteria. Lichen are more accurately referred to as successful “mini-ecosystems.”

Because of their unique structure, lichens can tolerate some remarkable extremes in temperature and drought. Some can photosynthesize at -20°C and thrive in this extreme for years. Lichen have even done the spacewalk along with the hardy tardigrades and bdelloid rotifers, braving gamma rays and lack of oxygen to return to Earth, viable and happy to go on reproducing.

Lichens are truly badass collectives; they thrived for over 400 million years from the Early Devonian period and seem to break many of the standard rules of engagement through an unruly approach to life. It’s their downright unruliness that gives them an advantage in adapting to this varied and changing world. Below are just a few hallmark adaptations of this superorganism.

.

.

Shapeshifting Lichens Adapting to Drought and Deluge

Dry lichens are metabolically inactive and are often unaffected by pollution in this state. They can remain in this state for months, biding their time for the right conditions.

When a lichen is dry, it basically stops photosynthesizing. It becomes brittle and the photobionts are difficult to see beneath the protective fungal layer. In dry conditions a lichen will contain 15-30% water, enabling them to withstand drought for several months. When the lichen becomes moist, the surface goes translucent and the algae—visibly colouring the lichen in shades of green—actively photosynthesize within minutes as the water content in the lichen swiftly rises to over 80%.

.

.

A Lichen’s Unruly Lifestyle

All lichens consist of a structured association of photobiont (algae, and/or cyanobacteria) and mycobiont (fungi). The algae and/or cyanobacteria produce carbohydrates through photosynthesis; the fungus, which provides protective structure to the lichen, converts and stores these to the sugar alcohol mannitol. The cyanobacteria also takes nitrogen from the air and converts into products that the fungus can use for protein synthesis. The fungus (mycobioint), in turn, produces secondary metabolites with many uses by the lichen.

.

Adapting to Any Substrate Through Lack of Roots

Unlike plants, lichens lack roots, getting their water, nutrients and minerals from the air, dew, fog, rain and runoff. Some lichens use rhizines to cling to substrates but these don’t serve like roots to get water and nutrients. They simply help anchor the lichen to its substrate. Because lichens don’t generally rely on their substrate for nutrition, they can live on many nutrient-poor habitats, including rock, hardpan, and concrete. They also grow very slowly, which allows them to brave extreme environments by making smaller demands.

.

.

Adapting to Extreme Elevations

Rock-dwelling Lichens have been observed at extreme elevations. The Elegant Sunburst Lichen (Xanthoria elegans) was recorded by a Himilaya expedition in 1972 at an elevation of 7,000 m in the Karakorum. Granite-Speck Rim Lichen (Lecanora polytropa) was observed on the south side of Makalu at 7,400 m. To survive, lichens at these elevations must contend with extreme temperature fluctuations, high UV levels and wind speeds, variable snow cover, and short growing seasons. It’s no wonder that the Elegant Sunburst Lichen was exposed to space conditions and simulated Mars-analogue conditions in the lichen and fungi experiment (LIFE) in 2008 on the International Space Station (ISS).

.

.

Adapting to Changing and Extreme Environments Through Morphology

Lichens use some interesting morphological adaptations together with secondary metabolites to survive the often extreme and changing environments they inhabit and flourish in. These include adaptations to UV radiation, high wind, extreme temperature, low or highly fluctuating moisture and desiccation, and air pollution:

Cortex: This fungal layer protects the algal layer from UV radiation in high elevations and exposed areas.

Crystals: crystals that occur in the algal layer (as a liquid-glass-like mixture) play a photoprotection role, absorbing UV radiation and other harmful wavelengths.

Calcium oxylate crystals: A thin layer of calcium oxylate crystals on the surface of the apothecia of many lichens (e.g. Physcia spp.), form a pruina, blue-grey and powdery, that helps deflect sunlight to protect the reproductive structures.

Anhydrobiosis: This is the ability of cells to survive dessication conditions through cell modification; along with vitrification, an antioxidant system and the ability to go dormant, this has allowed some lichen to survive space conditions for durations of up to 1.5 years (DeVera, 2012). Lichen can restore photosynthesis within minutes to an hour of rehydration.

Vitrification: This is the ability to convert algal symbionts to a glassy state to survive low water content.

Cavitation: This is the collapse of lichen fungal cells when dry.

Antioxidant system: a system that counteracts oxidative stress associated with wetting and drying cycles by entering a kind of suspended animation that can last for months to years.

Slow growth: The slow growth of lichen allows them to survive in harsh conditions through less demand.

Dormancy: This ability to shut down systems when conditions are too severe allows the lichen to ride out bad conditions and start up within minutes of resumption of good conditions.

.

.

Adapting to Changing Environments by Swapping Partners

In a previous article I wrote about lichen stealing, algal swapping, and photobiont mining. These strange actions are apparently ubiquitous within the lichen world and they appear to play a vital role in lichen adaptation to varied and changing environmental conditions. “Association with a wide range of symbionts may help lichens survive under harsh environmental conditions,” write Moya and colleagues in their 2020 article in Scientific Reports. In their 2024 article in MycoKeys, Nimis and colleagues document how lichen that grow on lichen (lichenicolous lichen) regularly start as ‘parasites’, mining the host lichen for its photobiont, before finding their own preferred partner.

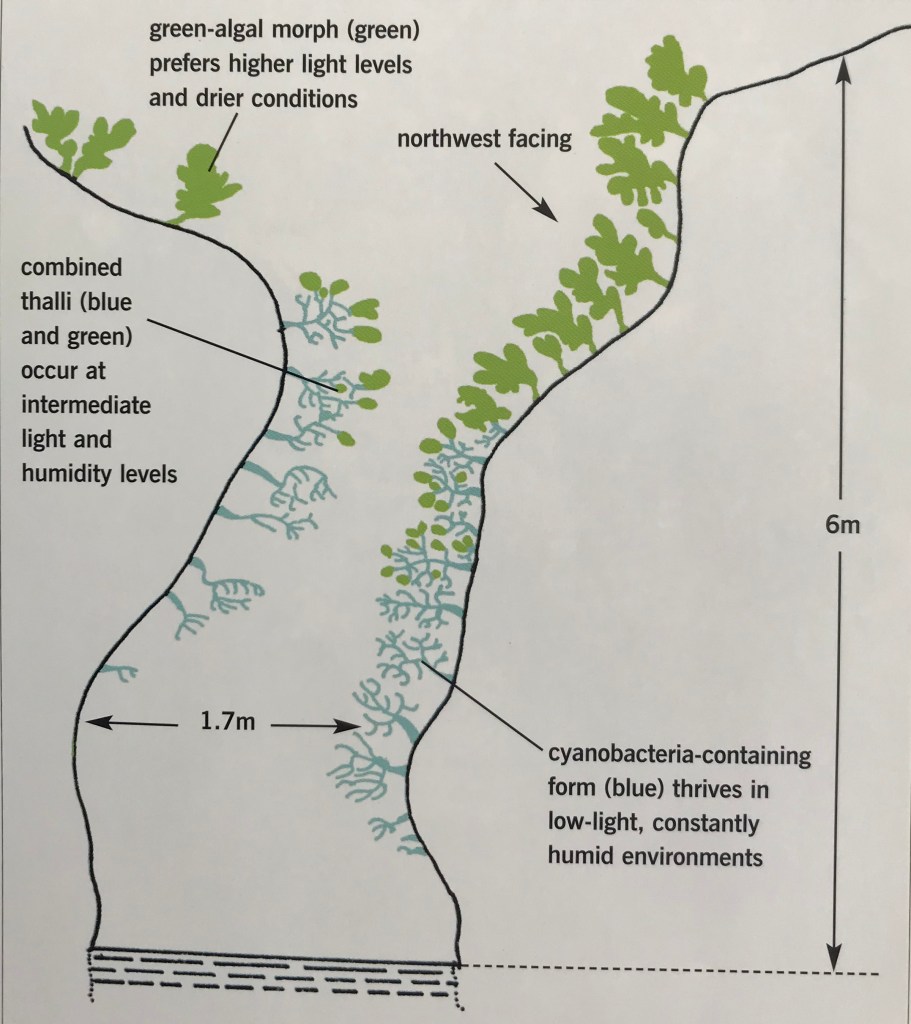

Purvis tells us that there are many examples of algal switching, particularly in the foliate lichen, such as Nephroma, Sticta and Lobaria. In these groups, the same fungus may be associated with either a green alga and appear leaf-like or with a cyanobacterium and often looking shrub-like or as tiny granules. These are called photomorphs, when a different photobiont partners up with the same mycobiont of the same lichen. The different photobionts can either occur together in the same thallus (possibly in different parts of the thallus) or separately. So, the same lichen (the same fungal partner) may look like two different lichen—two different photomorphs—when, in fact, they are the same lichen. Purvis argued that environmental factors, such as light and humidity, determined which photobiont was present in the lichen.

.

.

This all sounds rather licentiously polygamous. But it’s very successful—and presumably consensual. The argument goes like this: The mycobiont shapes its structure to optimize the capture of light and nutrients by its symbiotic photosynthesizing partner. Different photobiont species have varying photosynthetic rates, cell sizes, and growth patterns; these influence how the fungal hyphae arrange themselves to optimize symbiosis. The ecological implications lie in the ability of a particular lichen to occupy a wider range of habitats and adapt to different environmental conditions by selecting, stealing, and swapping partners.

.

Adapting to Harsh Environments through a Wandering Lifestyle

“Air lichen” tumble through the air, itinerants that wander the semi-arid to arid regions in search of a suitable place to land. Also called ‘vagrant’ or ‘vagabond’ lichen and compared to tumbleweed, these lichen remain unfixed to any substrate and simply blow in the wind from location to location. A good example is the Tumbleweed Shield Lichen (Xanthoparmelia chlorochroa), which is abundant on the High Plains of Wyoming. The fruticose Richardson’s Masonhalea Lichen (Masonhalea richardsonii) curls up when dry and spreads by the wind across the open northern tundra of Canada.

The Germans call these wandering lichen Wanderflechten. Purvis shares the story of how in 1829, during the war between Russia and Persia, a town on the Caspian Sea was suddenly covered by a lichen—Lecanora esculenta—which literally fell from heaven. It was made into bread and eaten by starving people. Sounds a bit like manna?…

.

Adapting to Varied Environments through Chemistry

The lichen’s adaptive life-style is aided by the production of more than a thousand chemical compounds (including secondary metabolites and pigments) that act as sunscreen, and help them fend off herbivores and insects, prevent freezing, reduce competition by other lichen, and stop seeds and spores from germinating in their soft, moist tissue.

Lecanora and Umbilicaria produce secondary metabolites that have an allelopathic effect (e.g. reduces competition by inhibiting the growth of other lichen and plants). These include orcinol, protocetraric acid, atranorin, lecanoric acid, nortistic acid, usnic acids, and thamnolic acid. Some lichen allelopathic chemicals also act as antioxidants and insecticides, and are antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and antiparasitic—to name just a few. This is likely why, even though lichen grow slowly, they remain resistant to decay microorganisms and are generally not eaten by generalist herbivores (excluding caribou and some specialists) and insects.

Usnea and Xanthoparmelia use usnic acid as sunscreen against UV-B radiation. It also gives these lichen their characteristic pale yellowish-green colour. Usnic acid also acts as an antimicrobial agent, an antibiotic, antiviral, antimycotic, antiprotozoal, antiherbivoral, antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic agent.

Just as with aquatic algae, the photobiont of a lichen can be damaged by too much light, particularly UV light, so it uses pigments as ‘sunscreen.’ Lichens with the most intense colours are those most exposed to sunlight and lack of moisture. This is why Xanthoria is bright yellow in sunny places and grey to green (depending on moisture) in shady places.

Some lichen acids can help detoxify toxic metals. Lichen acids, such as oxalic acid may help dissolve insoluble essential minerals necessary for lichen growth. Hydrophobic (non-wettable) lichen substances improve gaseous exchange in the medulla. This is particularly important for lichens living in wet habitats because they can’t photosynthesize if they are too wet.

.

.

The Lichen at the End of the World

I can’t help thinking that one of the reasons for lichen’s singular success over millennia of extremely diverse conditions and climate changes is that they are not singular; they are a consortium of several organisms acting in concert, as a community: a fungus, alga / cyanobacteria, yeast and bacteria. A single lichen is a multicultural country, whose diverse voices and talents help it adapt to encountered differences through its own acceptance of differences within it. A country that celebrates its differences recognizes that these unite us through tolerance and inclusivity and help keep us open to change.

Now, that’s success!

References:

Friedl, T. 1987. “Thallus development and phycobionts of the parasitic lichen Diploschistes muscorum.” Lichenologist 19(2): 183-191.

Heidmarsson, Starri, Jan-Eric Mattsson, Roland Moberg, Anders Nordin, Rolf Santesson & Leif Tibell. 1997. “Classification of lichen photomorphs.” Taxon 46: 519-520.

Hawksworth D. and M. Grube. 2020. “Lichens redefined as complex ecosystems.” The New Phytologist 227(5): 1281-1283.

Insarova ID. and EY. Blagoveschchenskaya. 2016. “Lichen Symbiosis: Search and Recognition of Partners.” Biology Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences 43(5): 408-418.

Moya, P. A. Molins, S. Chiva, J. Bastida, and E. Barreno. 2020. “Symbiotic microalgal diversity within lichenicolous lichens and crustose hosts on Iberian Peninsula gypsum biocrusts.” Scientific Reports 10(1): 14060.

Nimis, Pier Luigi, Elena Pittao, Monica Caramia, Piero Pitacco, Stefano Martellos, and Lucia Muggia. 2024. “The ecology of lichenicolous lichens: a case-study in Italy.” MycoKeys 105: 253-266.

Purvis, William. 2000. “Lichens.” Natural History Museum, London. 112pp.

Richardson, DHS. 1999. “War in the world of lichens: Parasitism and symbiosis as exemplified by lichens and lichenicolous fungi.” Mycological Research 103(6): 641-650.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

One thought on “The Lichen At the End of the World”