It was shortly after a long spring rain when I discovered this crustose lichen beside several other lichens I was examining on a fallen sugar maple branch from the earlier calamitous ice storm.

.

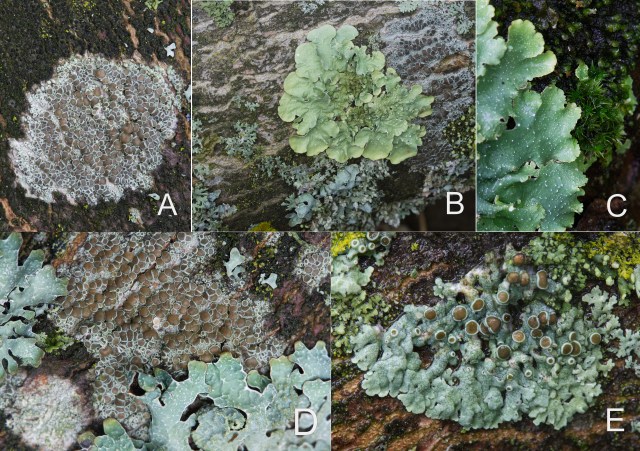

I was looking at several old friends I’d seen on my studied maple tree: foliose lichen such as the Common Greenshield (Flavoparmelia caperata), Rough Speckled Shield Lichen (Punctelia rudecta), Hammered Shield Lichen (Parmelia sulcata), and Frosted Rosette Lichen (Physcia biziana). There was also Hooded Rosette Lichen (Physcia adscendens), Candleflame Lichen (Candelaria concolor) and a shadow lichen (probably Phaeophyscia orbicularis). And surrounding them all in a rough sea of granular green, spreading like blue chicken pox, was the crustose City Dot Lichen (Scoliciosporum chlorococcum) with its granular green thallus and dark blue apothecia. There were also several distinct roundish growths of the crustose Brown-Eyed Rim Lichen (Lecanora allophana), some with bursting apothecia. Yes, really bursting! I saw the algal partner, likely a Trebouxia, in its green glory in places. According to Veselá and colleagues this is a common sight with leprose lichens such as all Lecanora species in the process of apothecia breaking open during periods of high moisture to release their spores. But that’s for another Wednesday…

.

.

Amid the splashy larger lichen there was the understated crustose fluff-wart lichen, the Bitter Wart Lichen (Lepra amara [formerly Pertusaria amara]), adding small circular patches of whitish pale green to greenish grey thalli, weakly zoned at the margins. I’d seen Bitter Wart Lichen before on a poplar in another forest nearby. And here it was again, looking handsome with its pale greenish thallus and warts of yellow-green punctiform soralia.

The Bitter Wart Lichen is commonly found on deciduous as well as coniferous trees and gets its name from the strong persistent bitter taste of the secondary metabolites (e.g. picrolichenic acid and protocetraric acid) present in the lichen’s thallus. Tasting a small bit of the thallus will produce a highly bitter flavour in the back of the mouth that will persist. Though unpleasant, it is not poisonous, and is a sure way to distinguish this species from the very similar Pore Lichen (Lepra albescens). The taste test shouldn’t be necessary though, MinnesotaSeasons.com tell us, because Pore Lichen is very rare in North America. A bitter ‘aspirin’ taste indicates the presence of picrolichenic acid, the more bitter of the two metabolites. In his book Lichens of the North Woods, Lichenologist Joe Walewski tells us that the metabolites causing the bitter taste of the Bitter Wart Lichen was the basis for the lichen’s use for controlling high fever. The bitter quality presumably acted like quinine. According to Plantiary, this lichen contains anti-inflamatory, antiseptic, and anti-pyrectic properties, helping to treat fevers, gastrointestinal disorders, and skin conditions. The lichen is high in Vitamin C and A, calcium and iron, boosting immunity and supporting digestive health.

.

.

Italic 8.0 tells us that the Bitter Wart Lichen is not only a common epiphyte with a wide ecological range, but often competes aggressively for resources, “able to overgrow other crustose lichens and sometimes even bryophytes.” Its competitive success arises partly from those bitter secondary metabolites that deter herbivores and insects from grazing on it and giving Lepra amara an advantage over other lichens that lack these bitter deterrents.

.

.

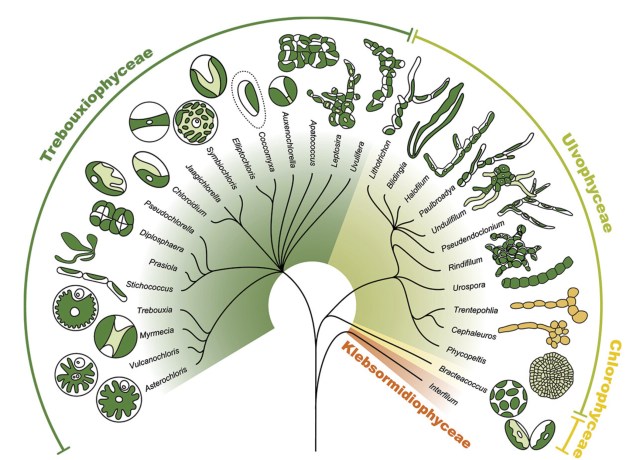

The algal partner in Bitter Wart Lichen is the green alga Trebouxia, a common algal partner in lichens. Its bright green wandering form (out of its symbiotic lichen ‘cage’) can be seen in my photo above of this lichen’s wet form. Unlike some lichen algal partners, Trebouxia does not require lichenization to survive; it can survive outside of the lichen symbiosis, as a free-living organism, either alone or in colonies. According to Sanders & Masumoto (2021), many algal partners in lichens are facultative photobionts, with the ability to live and thrive independently of the mycobiont.

.

.

.

References:

Sanders W.B. & Masumoto H. 2021. “Lichen algae: the photosynthetic partners in lichen symbioses.” The Lichenologist 53: 347–393.

Veselá, Veronika, Veronica Malavasi & Pavel Skaloud. 2024. “A synopsis of green-algal lichen symbionts with an emphasis on their free-living lifestyle.” Phycologia 63(3): 317-338.

Walewski, Joe. 2007. “Lichens of the North Woods.” Kollath & Stensaas Publishing, Duluth, MN.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

One thought on “How Bitter Is The Bitter Wart Lichen?”