.

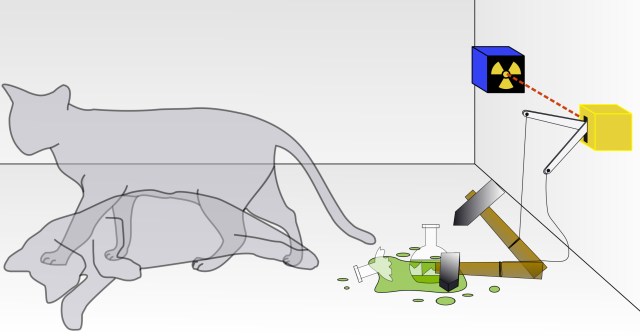

Most of us are familiar with the thought experiment in probabilities that physicist Erwin Schrödinger devised to illustrate the paradox of quantum superposition. Now commonly known as Schrödinger’s Cat, the experiment imagines a cat placed in a box with something that could kill it. Until the box is opened and observed, the cat is considered simultaneously dead and alive.

.

What does Schrödinger’s Cat have in common with tree snags, logs and stumps? My point is that they, too, are both dead and alive at the same time—only in reality, not just in probability. The log or snag has died and is in the process of rotting. But the dead tree also nurtures a diverse community of fungi, lichen, mosses and other saprotrophic organisms like worms, slugs, insects, rotifers, and waterbears that feed and live in or on the decaying wood. Even other trees grow on the rotting log or stump.

There’s an entire ecosystem’s worth there. And quite another world…

.

.

Decaying wood offers a source of nutrients for many forest dwellers. Stumps provide shelter and denning sites for many animals. As they decompose with the help of microorganisms, stumps enrich the soil and contribute to the cycling of nutrients in the entire forest ecosystem. Betts Ecology and Estates provide a good list of the biodiverse living forms that make a living on a tree stump. In their paper on tree regeneration on stumps in BC rainforests, Wong et al. give convincing arguments for the role that stumps play in forest ecosystems in maintaining biodiversity as coarse woody debris.

Tree stumps are not just remnants of trees; they are dynamic parts of an ecosystem that support biodiversity, nutrient cycling, and tree regeneration. I call them Schrödinger’s trees.

I found a Schrödinger’s tree in the swamp forest of the Trent Nature Sanctuary that captured my interest. I brought out my hand lens and examined this particularly vibrant cedar stump more closely. The dead stump was a living texture of dark to light green mosaics of moss and lichen. Hills and valleys of tufted moss crowded around islands of dark lichen with powdery horns that craned up to greet the day.

.

I spotted a tiny little brown mushroom (LBM) and a worm snaking its way through the moss jungle. I also saw a lone 1.5 cm high eastern hemlock seedling thrusting its way out of the mossy carpet, roots feeding off the moisture and nutrients of the rotting wood. Hoping to become a tree some day.

.

.

Common Powderhorn Lichen—Cladonia coniocraea

.

The Common Powderhorn (Cladonia coniocraea) is fruticose with two types of vegetative (thallus) forms: 1) flat, overlapping leaf-like scales (squamules); and 2) grayish-green slender unbranched stalks (podetia) that taper to a point or a very small cup (sexual apothecia). The upper two-thirds of the podetium is mealy with the covering of soredia (asexual reproductive cluster of algal cells wrapped in fungal filaments).

.

I found patches of this fruticose lichen here and there on the cedar stump often nestled among fork moss, often spilling over the ‘cliffs’ of the stump. The lichen’s tapering, often bent podetia (horn-like stalks that may hold spore-bearing cups or apothecia) rose out of beds of crinkly green scale-like squamules. Many of the squamules were thick with soredia, particularly on their edges. The podetia were mealy (with soredia) and a wonderful shade of green. I noticed that the top ends of several tapered podetia were whitish or pruinose, likely from a powdery coating of soredia, known to occupy the tips of podetia. The very tops of a few of these tips were brown and these were very likely the rare apothecia noted but not often seen.

.

.

As its name implies, this lichen is very common, particularly on rotting wood and tree bases. I’ve seen it flourishing on rotting cedar logs as well as other trees and growing on moss on a granite boulder. According to NatureSpot it is pollution resistant and widespread in urban forests that provide some shade.

.

.

Mountain Fork Moss—Orthodicranum montanum

.

The Common Powderhorn was often nestled in a cushion of bright green wiry Orthodicranum montanum (formerly Dicranum montanum), which formed dense hairy tufts of lanceolate leaves throughout the stump, but mostly along the ‘cliffs’ of the stump. Described by Consortium of Bryophyte Herbaria as preferring bark of tree bases or rotting stumps and logs, this cushion moss has clustered branchlets, erect-spreading costate leaves and is strongly crisped when dry; hence its other common name of Crispy Broom Moss.

.

Sheet Moss—Hypnum curvifolium

.

This beautiful fern-like plumose branching moss was glossy, with intertwining ribbons, 0.3-3 mm wide stems and curved leaves. Its flat lying stems were regularly divided with short branches and crowded overlapping leaves, sickle shaped, triangular and gradually pointed. Aptly called sheet moss, Hypnum curvifolium formed a sheet on the flat ‘bowl’ of the stump. It is also called “Greater Plait Moss” for its plaited ribbon-like leaves and is a larger form of its sister Cypress-leaved Plait-moss (Hypnum cuppressiforme). It is commonly found on logs and the forest floor, preferring shady, humid conditions out of direct sunlight and a surface rich in organic matter.

.

.

Long-Leaved Cedar Moss—Brachythecium acuminaturm.

.

I identified long strands of Brachythecium moss amid the hairy Orthodicranum and feathery Hypnum (see above photos). It was likely Long-leaved Cedar Moss (Brachythecium acuminatum), a common moss on trees with creeping cylindrical stems, broadly lance shaped and narrowing to a point.

.

Baby Tooth Moss—Plagiomnium cuspidatum

I also saw small patches of delicate leaved Plagiomnium cuspidatum resembling the tiny leaves of thyme, arranged in pseudo whorls (see photo with mushroom above). In fact, it also goes by the name Woodsy Thyme-Moss. Its preferred base-rich habitat consists usually of the base of trees or tree stumps, rich in organic matter. It is commonly found on tree bases, stumps, coarse woody debris in wet forests.

.

How Trees Can Save Us

In my 2019 article in Impakter, I explore the perspectives of five writers on the role and history of trees in global planetary health and our journey with climate change. I think it pertinent and of interest following this exploration of a Schrödinger’s tree: the ‘other world’ of a tree stump.

.

.

References:

Jenkins, Jerry. 2020. “Mosses of the Northern Forest.” Comstock Publishing Associates. 176pp.

Munteanu, N. 2019. “How Trees Can Save Us.” Impakter, January 24, 2019.

Wall Kimmerer, Robin. 2003. “Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses.” Oregon State University Press. 176pp.

Wong et al. 2022. “Tree regeneration on stumps in second-growth temperate rainforests of British Columbia, Canada.” Global Ecology and Conservation 37.

.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

3 thoughts on “Schrödinger’s Tree & the Cedar Stump”