Since moving back to the Lower Mainland of British Columbia after living for a while in Ontario, I’ve been reacquainting myself with the local forests. My son reminded me that I used to drive him to Watershed Park when he was a teen to ride the mountain bike trails through gorgeous Douglas fir-cedar-maple forest. The park gets its name from the forested bluff that protects a series of freshwater springs of an underground aquifer in Delta, BC. Midway down the Water Tower Trail is a water fountain and tap, drawing fresh spring water for park hikers and cyclists.

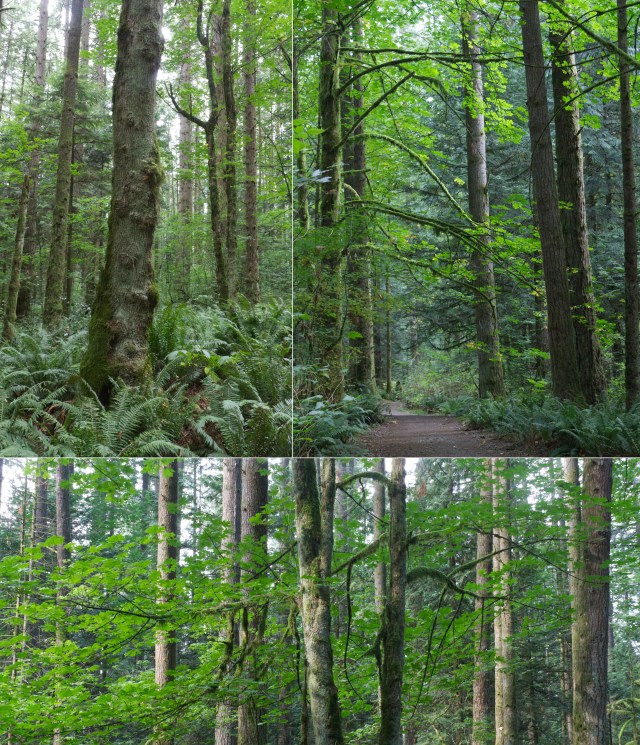

Sun-streaked Douglas fir forest, Watershed Park, BC (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

Watershed Park

.

Inhaling the intoxicating fresh aroma of conifers, moist vegetation, and humus, I crane my neck to gaze up high at the tall canopy that seems to touch the heavens. The stately Douglas fir trees rule this forest, tall majestic trunks soaring high to capture the western light. Beneath their deep green canopy, a cornucopia of texture and colour—a bazillion shades of green and brown—carpet the understory and the spongy ground. Rapt with joy at witnessing and experiencing this complex ecosystem, I fall silent with reverence. I listen to the silence of the forest, and it eventually yields subtle notes of forest life talking to itself. Trees and shrubs murmur softly, tickled by a rustling wind. A few birds call out. Mostly bluejays, shrill notes echoing. A few chickadees sing cheerfully as they flit effortlessly from branch to ground and back to branch again. Two squirrels bash through the undergrowth in lively chase—as if they rule the forest.

Watershed Park is about 153+ hectares in size and riddled with 11 km of trails for cycling and hiking. It is protected from logging, even as it is bordered by commercial, residential and industrial sites, with Highways 10, 91 and Scott Road running along its perimeters.

.

This community park runs along Cougar Creek and beside Burns Bog in Delta, within the Coastal Douglas Fir Biogeoclimatic Zone (CDF)—which makes up only 0.3% of BC and is both high priority for preservation (home to 29 endangered plant communities) and most at risk zone in BC (due to logging and encroaching development). This zone is protected in conservation areas, such as Watershed Park.

.

I’ve been going to Watershed Park ever since I returned to Ladner and I like to call it ‘my forest.’ Located in Delta, this forest shares many common traits with typical coastal rainforests along the BC coast: a rich overstory of Douglas fir and western red cedars, accompanied by an understory of big leaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), smaller vine maple (Acer circinatum) and the occasional red alder (Alnus rubra), trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides), and mountain ash (Sorbus americana) trees at lower elevation, closer to Cougar River.

Douglas firs tower high as overstory trees in Watershed Park, BC (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

.

Aside from the Douglas fir-dominated tree-scape and associated understory, the main difference between this raincoast forest and the old-growth forests I’ve encountered in Ontario (e.g. eastern hemlock-eastern cedar-sugar maple-hophornbeam), was the plethora of ferns and mosses—not only on the ground and rocks, but on the trees and ‘dripping’ off the branches; lending credence to the term ‘rainforest.’ Other common underbrush included Oregon grape (Berberis aquifolium) and huckleberry (Vaccinium parvifolium). Other ground cover included Herb Robert (Geranium robertianum), trailing blackberry (Rubus ursinus), wild gooseberry (Ribes uva-crispa) and several others.

.

My favourite walk is a 2.5 km loop, first down the Water Tower Trail to the Lower Trail, turning west on it to its end then winding my way back up to the Pinewood Trail, and looping back to the water fountain for a drink of fresh spring water and finally up to my car, parked on Kittson Parkway. The walk takes roughly an hour—longer if I’m taking photographs—giving me a view of many of the large trees, snags, stumps and associated mosses, ferns, lichens and fungi that inhabit this rich and diverse ecosystem.

.

.

Fungi in Watershed Park

In late fall, I began to see fungal fruiting bodies everywhere, on the ground and on the trees, on decaying logs and stumps.

.

Fall is a wonderful time to spot fungi in the forest; this is when they put out their fruiting bodies and spread their spores to make more of themselves. One particular mushroom–Zeller’s Bolete (Xerocomellus zelleri)–seemed to be everywhere, but particularly near any large Douglas fir–as if drawing from its strength and resources. Or was it the other way around? I started spotting this bolete’s distinctive red stem, grey-brown to nearly black cap with pores instead of gills at its underside in October. By November the stems of the older boletes started losing their crimson colour, becoming more yellow, and their caps faded to a brownish red colour. Many started listing as they decayed and fell prey to slugs that seemed to prefer their porous caps.

.

.

Zeller’s Bolete is only found in western North America, ranging from British Columbia south to Mexico. With fruiting bodies growing mostly on the ground in late summer and autumn, this bolete is most often found in Douglas fir forests and it’s edible, though not a choice mushroom to eat.

.

.

I found the jelly fungus Yellow Stagshorn (Calocera viscosa) on decaying logs and ground litter throughout the forest. Like most jelly fungi Calocera viscosa grows on wood, but the wood is usually moss-covered and often buried, so that the mushrooms appear terrestrial. More orange than yellow, this wood-rotting fungus with antler-like branches grows up to 10 cm high.

.

.

I also found many colonies of White Coral mushroom (Clavulina coralloides), also called Wrinkled Coral fungus or Crested Coral fungus, on the ground amid the moss, near the Douglas firs. This delicately beautiful creamy white branching mushroom is actually quite tiny, reaching about 2 cm high, and typically found in conifer forests such as Watershed Park where it is ectomycorrhizal: forming a sheath around the root tips of trees and exchanging nutrients with them. It is edible but some think it too tough to enjoy. I noticed that some of the fungi were turning grey-blue from the base upwards. This, I later found, is caused by the ascomycete fungus Helminthosphaeria clavariarum, which spreads from the base up.

.

Ferns in Watershed Park

.

The forest floor of Watershed Park was a verdant blanket of ferns: mostly Western sword fern (Polystichum munitum), deer fern (Blechnum spicant), lady fern (Athyrium filix-femina) and western bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum). I found Licorice fern (Polypodium glycyrrhiza), mostly as an epiphyte on the big leaf maple trunks and branches, keeping company with thick carpets of various mosses.

.

Bryophytes & Lichens in Watershed Park

Watershed Park’s rich and damp forest ecosystem harboured a plethora of bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) and lichens that are often substrate-specific: living on soil and humus (terricolous); on bark of trees trunks (corticolous), branches, and tree bases; and on decaying stumps and rotting logs and wood (lignicolous).

Mosses & Liverworts

I’m told that bryophytes are influenced by local microhabitat characteristics, which can vary on a scale of millimetres to centimetres and, because substrate conditions can be short-lived, bryophyte communities don’t exist in equilibrium conditions; in other words, they move around and come and go. For partly this reason, competition is not a major factor shaping these communities like it is with vascular plants. Examples of influential microclimates include light, temperature, local moisture and how these operate (e.g. duration and intensity of light). Bryophytes have several regeneration strategies to equip them for their every changing habitat conditions and allow them to establish quickly, following a disturbance. For instance, they are mostly clone organisms, able to recolonize quickly.

I’m also told that in humid climates—like the temperate rainforest such as Watershed Park—species may not be confined to one substrate type as they are in drier conditions; they might thrive on several substrates once the moisture limitation has been removed.

.

.

I found Oregon Beaked Moss and waved silk moss mostly concentrated at the base of Douglas fir trees. Other mosses like mountain fork moss and cat-tail moss grew quite a way up the trunk of the Douglas fir tree. I found other mosses, such as curved silk moss, on many substrates, from rotting logs and stumps to the base and trunk of several tree species. Cat-tail moss was both versatile and abundant in the forest, draping off vine maple branches, or streaming down deeply furrowed Douglas fir trunks.

.

.

The forest floor—from ground to fallen logs and branches—was densely covered in a thick brilliant green carpet of mostly mountain fern moss (Hylocomium splendens). Hylocomium splendens is also called step moss, given how it forms its new growth each year in step-fashion from a bend in the previous frond. The yearly growths of this moss together resemble an undulating tiny forest of miniature ferns and, like Sphagnum, form a spongy multi-layered mat.

.

.

I found Coastal Leafy Moss or Badge Moss (Plagiomnium insigne), on the shaded moist humus ground also occupied by a ‘forest’ of Herb Robert (Geranium robertianum), a wild geranium with tiny pink five-petal flowers. I also identified patches of Rose Moss (Rhodobryum roseum), which thrives in moist, shaded forests dominated by Douglas fir. It forms lush, rose-shaped rosettes of leaves on upright stems that grow from horizontal, creeping stems. This moss typically indicates a healthy forest ecosystem with sufficient moisture and nutrients.

.

.

Each tree supported a unique ecosystem for mosses, lichens and liverworts. This makes sense, given the unique texture and chemistry (such as nutrient availability and pH) of a tree’s bark. For instance, the red alder, which is often found in verges where sunlight is plentiful and whose neutral to acidic bark tends to remain smooth—even in older trees—harbours a uniquely rich set of lichen and mosses, not seen on other trees. The deeply furrowed acidic bark of Douglas fir supported a distinctly different community.

Two views of Rhytidiadelphus triquetrus moss on a Douglas fir, Watershed Park, BC (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

Lichens

Various species of corticolous lichen colonized the bark of cedar, Douglas fir and Big Leaf maple trees. This included the crustose dust lichens (Lecanora spp.), various foliose lichens such as the Hammered Shield Lichen (Parmelia sulcata), the Centipede Lichen Heterodermia sp.) and fruticose lichens, such as the Common Powderhorn Lichen (Cladonia coniocraea).

.

.

.

What Grows on the Trees, Stumps & Logs

Over early to late fall, I spent some time studying the dominant overstory and understory trees for their mini-ecosystems and what life they supported.

Douglas Fir

.

Douglas fir bark harboured many distinct mosses, particularly at its base.

One particular tree was drilled with many northern flicker holes; these beautiful woodpeckers create deep, three inch diameter holes as nests, leaving a bed of wood chips at the bottom. The birds also peck at wood for insects, creating smaller dim-sized holes in straight, horizontal lines.

.

.

Amid the flicker holes, I found a dense cover of curved silk-moss (Plagiothecium curvifolium); this tiny and lovely ribbon-like moss covered much of the tree trunk. Its main habitats include shaded, moist coniferous woodlands, where it grows on decaying logs, stumps, soil, humus and the bases of trees, especially those with acidic bark such as Douglas fir (with pH as low as 3.3).

.

.

The liverwort Cephalozia lunulifolia (renamed Fuscocephaloziopsis lunulifolia) was growing like lace amid Plagiothecium curvifolium (see image above; look for more translucent fronds with lunar-looking leaves). Also known as moon-leaved liverwort, Cephalozia is a slender bryophyte, less than 1 mm across, with incurved pincer-like or moon-shaped leaves. It likes moist environments and prefers rotting logs, peaty banks or moist humus-rich soils.

Along the tree trunk I saw strings of Cat-tail moss (Isothecium stoloniferum) and puffy bright green tufts of curly mountain fork moss (Dicranum montanum).

.

.

Tucked in with the moss were extensive patches of greenish-grey squamules and distinctive horn-like stalks called podetia (fruiting bodies) of the lichen Common Powderhorn (Cladonia coniocraea). This lichen commonly grows on many substrates in shaded moist places, including litter or bare ground, fence posts, decaying wood such as rotting logs and stumps, and the bark of trees.

Common Powderhorn grows amid Mountain Fork Moss (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

At the base of the Douglas fir tree, I found healthy clusters of waved silk moss (Plagiotheium undulatum), looking like light green thick caterpillars, and feathery Oregon beaked moss (Kindbergia oregana) as well as Mountain fern moss, (Hypocomium splendens) on the ground around the tree.

.

.

Many of the Douglas fir trees were hosts to various polypores. Gonoderma oregonense, the Western Varnish Conk or westcoast reishi on several Douglas fir trees and hemlocks. Known to colonize Douglas firs, this bracket fungus causes root and butt white rot; I spotted it mostly on snags and downed trees. Another white polypore seemed more common on live trees.

.

This common white polypore on the Douglas firs in Watershed Park, was undergoing guttation; the process of excreting excess water through its pores as droplets (like dew drops), similar to how plants “sweat”. This happens when a mushroom absorbs water faster than it can release through evaporation, it “sweats” out the excess. The droplets aren’t just water; they contain a variety of bioactive compounds, beneficial substances that researchers are studying for potential medicinal use.

Guttating white polypore on Douglas fir, Watershed Park, BC (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

I also spotted several Douglas fir cones with tiny white mushrooms sprouting from them. These are simply known as Douglas fir cone mushrooms (Strobilurus trullisatus), common in the Pacific Northwest and often a sign that the mushroom season is beginning.

.

.

Big Leaf Maple & Vine Maple

.

I identified several mosses and liverworts that seemed to prefer the big leaf maple bark, often starting at the base and working their way up the trunk. These included Oregon Beaked moss (Kindbergia oregana), slender mouse tail moss (Isothecium myosuroides sp.) and the Tree Ruffle Liverwort (Porella navicularis). This liverwort is commonly seen on maples and alders. I also spotted dust lichens (Lepraria spp.) on several maples as well as nearby cedars and Douglas firs. Looking like light green patches of sprayed paint, these ubiquitous lichen are commonly found on maple bark, but also occur on several conifers. In fact, my hike revealed that many of the Douglas fir trees were covered in a healthy dusty spray of these lichens.

Big leaf maple stands amid sword fern, Watershed Park, BC (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

.

I encountered many vine maples, their beautiful tender green leaves adding a living froth of green to the forest. These understory shade-tolerant trees are native to the moist forests of the Pacific Northwest. The vine maple thrives in moist, nitrogen-rich soils, often forming dense thickets. I found Cat-tail moss streaming down their slender trunks and draped down like green waterfalls from every branch and twig.

.

.

Red Alder

.

The red alders hosted several mosses, including the Feather Moss (Brachythecium) and Oregon Beaked Moss (Eurhynchium oreganum), common on red alders. The most dominant moss, from the tree base up the tree was Cat-tail Moss (Isothecium myosuroides) with their ‘tails’ swinging down in waves. I also noticed Tree Ruffle Liverwort, Porella navicularis (an old friend I’d seen growing at the base of several old sugar maple trees in Ontario), growing among the Cat-tail moss. Farther up the tree, I found patches of Dusty Fork Moss (Dicranum fuscescens) and Pincushion Moss (Ulota crispa).

Check out my article on the red alder for a comprehensive study on the mosses and lichens growing on the bark of several old red alders from a nearby forest.

.

Two Redcedar Stumps & Rotting Logs

I documented the living growths on two large rotting cedar stumps (>55 cm dbh). Growths included mostly mosses, liverworts and some tiny fungi.

.

Both cedar stumps were covered mostly with Variable-leaved Crestwort (Lophocolea heterophylla), a very tiny liverwort that typically grows on rotting logs, soil, and the base of trees in British Columbia woodlands. This tiny leafy liverwort is about 1-2mm wide and a centimeter long, with occasional lateral branches about 1.5 mm long. Their overlapping leaves are also often ‘forked’, divided into two lobes at their tips.

.

Another liverwort, with 5 mm wide shoots several cm long, formed patches interwoven with the tiny creswort. This was the Grove Earwort (Scapania nemorea), whose overlapping broadly rounded leaf lobes have tiny teeth along their edges. This liverwort likes decaying wood in humid, shaded habitats.

Among the dense liverwort cover were patches of Waved Silk Moss (Plagiothecium undulatum), forming thick pale-green ‘tails’. I also found some Curved Silk Moss (Plagiothecium curvifolium) forming a tight mat on the rotting red wood.

.

There were also small clusters of Pellucid Four-Toothed Moss (Tetraphis pellucida) on the stump. This interesting moss is known to thrive on rotting cedar wood, which provides a moist, acidic substrate particular to its growth. I identified it by its tiny upright, tufts of green shoots (8-15 mm high) and its splash cups—a peristome of four triangular teeth—that hold tiny green gemmae, resembling ‘nests and eggs’.

.

Growing down the horizontal face of the mossy stump were several orange waxcap (Hygrocybe) mushrooms and mostly on the top of the stump several tiny brown-grey striped mushrooms about 5 mm tall, which I identified as Clustered Bonnet (Mycena inclinata).

At the base of another rotting cedar stump, I found a cluster of goblet waxcaps (Hygrocybe cantherellus). This decomposing fungus typically forms clusters on decaying wood during the fall.

I saw many tiny mycena mushrooms on other moss-covered logs. One, the tiny and beautiful Bleeding Bonnet (Mycena sanguinolenta) was, in turn, colonized by another fungus, Bonnet Mold (Spinellus fusiger), a pin mold that parasitizes many genera of Mycena. The parasite grows inside the mushroom, without killing it, taking nutrients from the flesh and releasing hair-like structures out of the Mycena cap like a bad hairdo. Spinellus’s dark, round sporangia at the ends of its filaments contain spores that eventually disperse, looking for another mushroom to eat.

On the cut end of another bark-stripped stump, likely a maple or alder, I found another tiny mushroom (up to 1 cm high and wide), with a fibrous rosy-orange cap and a thick mottled stipe tapering to the bottom. I initially identified it as a tiny bolete after checking the bottom of the cap and finding no gills.

When I returned several days later, the caps had turned distinctly orange and when I re-examined the underside with my hand lens after cutting the mushroom open, I saw gills—not pores. What I thought might be pores was simply the fibrous partial veil of a young mushroom. So, back to square one…

.

This led me to another search and I came across the very common (some even call it invasive) Honey Mushroom (Armirallia sp.). Armirallia lives on dead and live wood of conifer and hardwood trees, often seen in dense clusters—as I did—on dead logs, stumps, and roots. They are found throughout British Columbia, in forests along the coast. Depending on where it is growing, Armirallia shifts between being a saprophytic decomposer on dead wood (breaking down dead plant and animal matter and returning essential nutrients to the soil) to a parasitic pathogen causing root or butt rot in living trees. This is also the case for many fungi; for example Kretzschmaria deusta, the Brittle Cinder Fungus, and Coprinellus domesticus, the endophytic inkcap. The relationship of the endophytic fungus with its host tree works on a continuum, potentially switching from mutualism to antagonism depending on environmental pressures; the endophyte becomes saprobic once the host starts dying, helping to decompose it and eventually returning nutrients back to the soil. These fungi demonstrate a versatile lifestyle by shifting from one role to another depending on the changing conditions.

.

.

On another log--possibly a Douglas fir--I discovered a large colony of LBMs (little brown mushrooms) that I did not identify further.

.

..

References:

Brodo, I. M. 2001. Lichens of North America. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

Brodo, I. M. 2016. Keys to lichens of North America: revised and expanded. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

Hylander, K. 2009. “No increase in colonization rate of boreal bryophyte close to propagule sources.” Ecology 90(1): 160-169.

Jonsson, B.G., and Esseen, P.-A. 1998. “Plant colonization in small forest-floor patches: importance of plant group and disturbance traits.” Ecography 21(5): 518-526.

Kimmerer, R.W. 2005. “Patterns of dispersal and establishment of bryophytes colonizing natural and experimental treefall mounds in northern hardwood forests.” Bryologist 108(3): 391-401.

La Roi, G.H. and Stringer, M.H.L. 1976. “Ecological studies in the boreal spruce fir forests of the North American taiga. II. Analysis of the bryophyte flora.” Can. J. Bot. 54(7): 619-643.

McGee. G., and Kimmerer, R.W. 2002. “Forest age and management effects on epiphytic bryophyte communities in Adirondack northern hardwood forests, New York, U.S.A.” Can. J. For. Res. 32(9): 1562-1576.

Menon, M.K.C., and Lal, M. 1977. “Regulation of a sub-sexual life cycle in a moss: evidence for the occurrence of a factor for apogamy in Physcomitrium.” Ann. Bot. 41(6): 1179-1189.

Mills, S.E., and Macdonald, S.E. 2005. “Factors influencing bryophyte assemblage at different scales in the western Canadian boreal forest.” Bryologist 108(1): 86-100.

Miyashita, Kesia Anne. 2013. “A bryophyte perspective on forest harvest: The effects of logging on above- and below-ground bryophyte communities in coastal temperate rainforests.” Master of Science Thesis, University of Alberta. 168pp.

Slack, N.G. 1990. “Bryophytes and ecological niche theory.” Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 104(1-3): 187-213.

Tng, D.Y.P., Dalton, P.J., and Jordan, G.J. 2009. “Does moisture affect the partitioning of bryophytes between terrestrial and epiphytic substrates within cool temperate rain forests?” Bryologist 112(3): 506-519.

Turner, P.A.M., and Pharo, E.J. 2005. “Influence of substrate type and forest age on bryophyte species distribution in Tasmanian mixed forest.” Bryologist 108(1): 67-85.

.

.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her most recent novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

2 thoughts on “A Walk in Watershed Park, British Columbia”