I love to walk the forest in the winter, whether I’m plowing through fresh deep snow, or crunching over hoarfrost-covered forest litter. Winter is a time for Nature to rearrange and remake itself.

.

.

I lived for over a decade in Ontario, at the gateway to Shield country—the land that belongs to millennia-old granite—an often harsh though beautiful landscape of wind-swept pines and golden marshlands. My forest walks took me along winding streams and rushing rivers, through old-growth hemlock stands, riparian cedars, majestic beech trees and tall sugar maples, oaks and hophornbeams, each canopy whispering its unique chorus—from wistful murmurs and creaks to haunting multi-timbral symphonies.

.

.

In early winter, the ground transforms into a spongy layer that often forms a crust as temperatures plummet at night and hoarfrost or rime settles on everything.

.

.

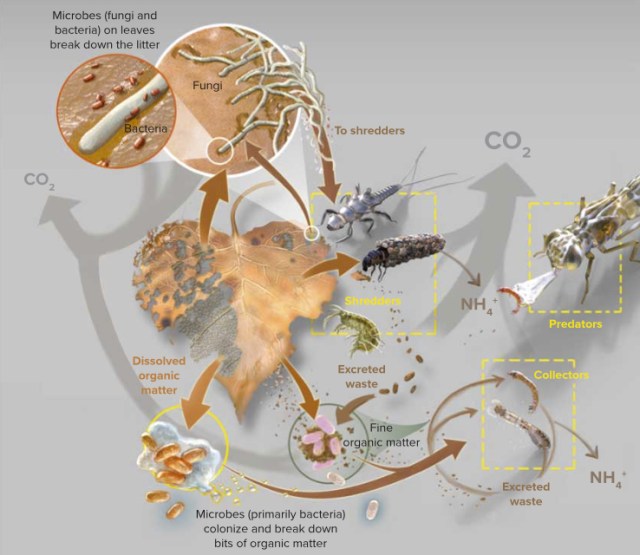

The dead leaves on the ground undergo strange transformations. Some had already changed colour from green to flaming reds and oranges or canary yellow or brilliant vermillion. Now fallen on the ground, turned grey or brown or even black, they transform again. Some of the leaves are mutilated, or skeletonized into reticulated patterns like delicate lace. Others have very round holes dug into them or chopped out of them. Yet others have ‘pimples’ or ‘potholes’ or blotches or smears of bubbling or jelly-like substances. All this depends on the agents at work: decomposers, saprotrophs, saprobic organisms. And all play a critical role in a larger and necessary phenomenon: decay. Decay is a vital transformation that ensures the health of the forest; decay is responsible for recycling usable nutrients back into the forest in a productive cycle of life. Agents of transformation include adult and larval invertebrates, fungi, protista and bacteria. All are responsible for continuing life on this planet by breaking down organic matter into usable nutrients—often used by the very same plants that donated the dead organic matter in the first place.

.

.

Ultimately, a single leaf—while providing important sugars to a tree through photosynthesis while it is alive—provides much to the tree when it is dead, through nutrient liberation upon decay.

.

.

According to leaf litter biologist Jane Marks, biologist at Northern Arizona University, dead leaves provide a primary food base for life up the food chain, from fungi and bacteria that initially colonize the leaves, and the insects that chew them, up to the birds and fish that eat the insects. This creates a “brown” food web more expansive than the “green” food web the leaves nourish when they are still alive, writes Marks. This brown food web—based on dead organic matter or detritus—involves the repackaging of energy that supports many life forms and several trophic levels in a healthy ecosystem and is often the dominant energy pathway in that ecosystem.

.

.

References:

Alves, Maria Cristina. “Decomposers: The Unsung Forest Allies.” Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center. https:// bayrestoration.org/decomposers-unsung-forest-allies [accessed 6/9/2022].

Marks, Jane. 2019. “Revisiting the Fates of Dead Leaves That Fall into Streams.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 50: 547-568.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. For the lates on her books, visit www.ninamunteanu.ca. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.