.

I’m constantly ‘in discovery’ when I walk the forest. Years ago, I made a pact with myself that I could not leave the forest until I had received three gifts—wonderful discoveries—that I could take home with me and nurture in my imagination. I had no idea how this one group of organisms would so significantly add to my gift list; they would both intrigue me and tickle all my senses of appreciation.

.

Kelly Brenner, author and naturalist, suggests that they are quite possibly the most strange thing you will encounter in the woods; she describes them this way: “There’s iridescent, there’s the cotton-candy pink ones, there’s some that look like champagne flutes with fireworks in them, and you look closer and the closer you get, the more it reveals and the more spectacular they are.” For instance, you can cut them up into pieces and they will fuse themselves back together—totally appealing to my sci-fi inclinations.

.

Weird Slime Bodies & Slime Names

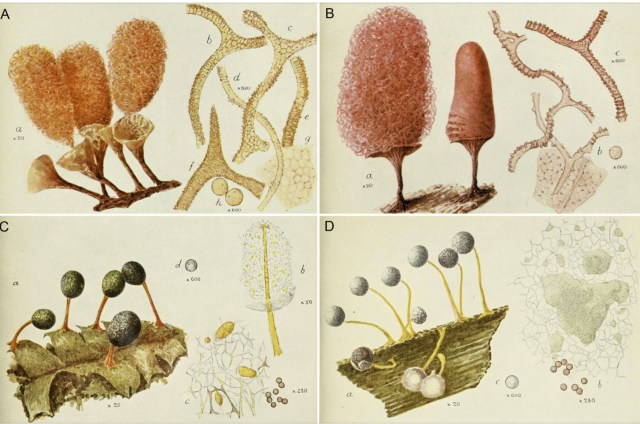

Perhaps because—or in spite of—the bizarre designs of their fruiting bodies, their intriguing behaviour and success and ubiquity despite remaining rather invisible and overlooked—slime molds have both defied taxonomic identification and been given some of the most colourful, disgusting, and wonderful common names. Some include: Moon Poo Slime, Wolf’s Milk Slime, Tree Hair Slime, Dog Vomit Slime, Bubble Gum Slime, Scrambled Egg Slime, Tapioca Slime, and Chocolate Tube Slime.

These often brightly coloured colonies can be spotted growing where fungi grow: on leaf litter, fallen logs, tree stumps, rotting wood, and dead vegetation. It’s their fourth phase in their life cycle that I’m observing. The first three phases are too small to see. In their first phase slime molds exist as groups of individual cells that swarm around in the soil, invisible without a microscope. These then gather to form the more conspicuous plasmodial stage, appearing as slimy blobs, often surrounded by networks of oozing cobweb-like structures that creep (unlike stationary fungi) in search of food. It is in this stage that they also often take on bright colours such as bright green, orange, pink, purple, blue, lemon yellow or flaming red. They also come in the ordinary colours of Nature’s brown and black. Slime molds feed on bacteria and fungal spores and other tiny things, growing on decaying organic material such as logs, snags, and stumps, leaf litter and other forms of humus and detritus.

.

.

Slime molds are bizarre life forms, once classified as fungus—because they sort of looked like fungi. Unlike a fungus that is not capable of absorbing and digesting their food internally, a slime mold can; they conduct phagocytosis—just like the amoeba I studied in school. slime molds are essentially amoeboid organisms currently classified under the polyphyletic grouping Mycetozoa belonging to the Kingdom Protista, which includes algae (e.g. diatoms) and protozoans (e.g., Paramecium). Fungi also don’t move, but slime molds do.

.

Weird Slime Behaviours

.

While some species’ single-celled plasmodia may move up to several millimeters in an hour (e.g. 1-5 mm/hr for Physarum polycephalum), they may charge into a rapid movement powered by internal cytoplasmic streaming (which cycles nutrients), reaching speeds of over 1 mm/second in fast-moving strands—the fastest speed known of any microorganism on Earth. That’s visible to the naked eye. Such rapid movement is encouraged by increased humidity and a food source such as bacteria or fungal spores. Slime molds may also ‘magically’ appear overnight and rapidly spread—covering close to a metre in 24 hours—but they may also rapidly transform, lose their fruiting bodies and disappear.

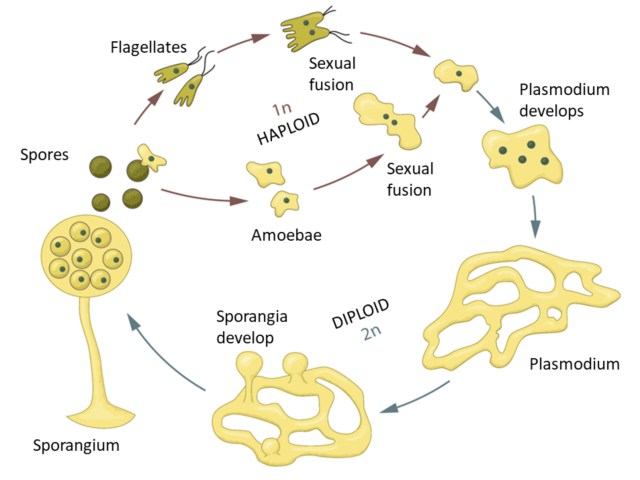

When the time is right, the slippery plasmodium makes fruiting bodies that release spores to create baby slimes to further populate the area. When a slime mold spore germinates, it releases an amoeba-like cell called a myxamoeba. If water is available, they develop flagella to swim. The odd shapes and brilliant colours of these fruiting bodies (sporangia) distinguish the many species that can exist in a single forest.

.

Weird Slime History

The first account of a slime mold was made by Thomas Panckow in 1654, who identified Lycogala epidendrum as a fast growing fungus: Fungus cito crescents. Another early slime mold champion was British naturalist Gulielma Lister who identified hundreds of slime mold species in the late 1800s and published the first comprehensive book, which she illustrated herself.

Lycogala epidendrum on a rotting log (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

.

Two hundred years after Lister published her guide to the mycetozoa, a team at Hokkaido University lead by Japan’s Professor Toshiyuki Nakagaki proposed that slime molds had a primitive intelligence that includes a kind of external memory. This was based on their discovery that the slime mold would always choose the shortest path in a maze that lead to a food source. What started out as “living creepies” are now at the forefront of artificial intelligence technological research.

Given their tiny soft bodies, slime molds have little to no fossil history. Their grouping is polyphyletic, consisting of multiple clades widely scattered across the Eucaryotes. They are suggested to date back some 600 million years. Scientists think there are around 1000 species, most in the plasmodial Myxomycetes, the only macroscopic scale slime molds and most of which are terrestrial. A plasmodium is an amoeboid, naked mass of cytoplasm that contains many nuclei, as opposed to individual cells with a single nucleus, forming a coenocyte. Under suitable conditions—say a warm rainfall—plasmodia form fruiting bodies that bear spores at their tips. Other slime molds are too small for us to see as individuals without help from a microscope.

.

Weird Slime Phylogeny and Taxonomy

Scientists have so far distinguished three types of slime molds based on their feeding and reproductive stages:

- Protostellids, a less studied possibly more primitive group of microscopic slime molds, form tiny, simple fruiting bodies on a cellular stalk.

- Dictyostelids (also known as cellular slime molds) tend to spend most of their existence in the form of singular amoebas; however, when food becomes scarce, the cells swarm into a multicellular aggregation, forming a ‘slug’ (called a grex) that coordinates the various cells, much like the brain of a multi-cellular organism—enabling it (them) to move to find food, and grows into a fruiting body; some morph into stalks and others into spores.

- Myxomycetes (known as the true or plasmodial slime molds) are the visible slime molds that—when food grows scarce and the ‘let’s gather’ signal goes out—converge and proeduce a whole new organism: a large, single-celled, multinucleated mass (a plasmodium), formed originally by a sporangia (spore-holding entity) to branch and spread, and forming often colourful fruiting bodies to release spores.

.

Weird Slime Intelligence

Slime molds have no brain, no organs; yet they exhibit a rudimentary intelligence and what’s called parallel processing power: capable of making decisions that lead to the most efficient path to sustenance and demonstrating complex behaviour with computational power and capacity for memory in a single-celled multiple-nucleated creature.

Interest toward harnessing slime mold intelligent movement has come from several areas including engineers, bio-artists, and town planners, robot designers and computer scientists.

.

“The slime mold doesn’t need to stomp or punch; it just spreads and consumes and fruits, expanding the microcosmos in its own body as it stakes a claim in our world.”—James Weiss and Deboki Chakravarti, Journey to the Micro Cosmos

.

References:

Smith, H.R. 2023. “A Slime of One’s Own.” Bay Nature magazine, January 3, 2023.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. For the lates on her books, visit www.ninamunteanu.ca. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.