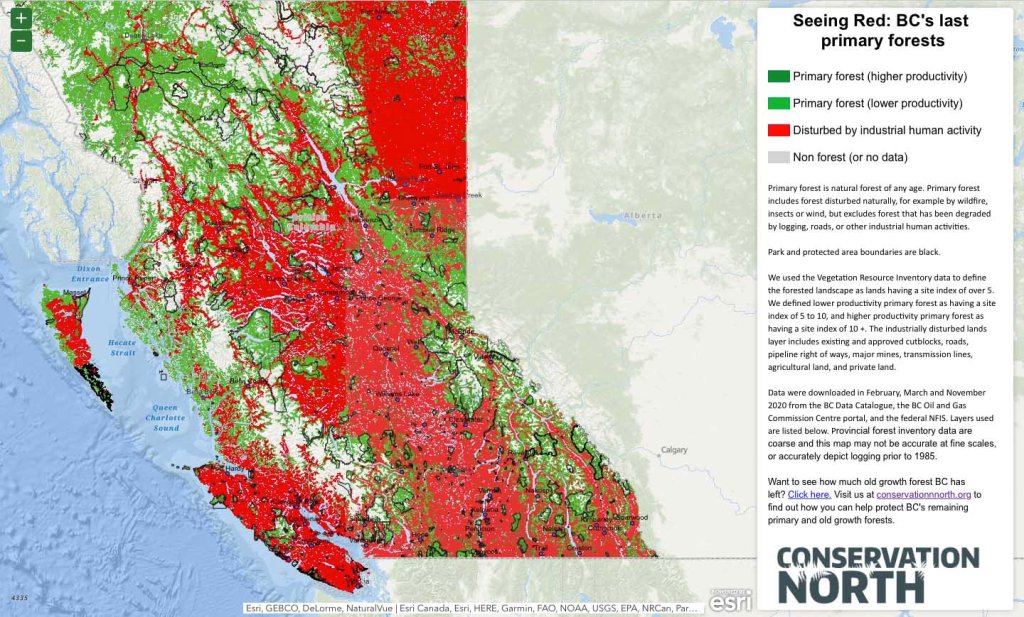

The map, which took one year to create from ten provincial and federal government datasets, shows both higher productivity (big tree rainforest) and lower productivity primary (original) forest, and areas disturbed by industrial human activity. Not all primary forests are old-growth, given that some are affected over centuries by natural disturbances such as wildfire. According to Conservation North director Michelle Connolly, one of the most striking things about the map is how little primary forest remains in BC’s interior; this includes the rare inland temperate rainforest, home of over 1,000 year old cedar trees and endangered deep-snow mountain caribou live in the spring and early winter, surviving on lichen found only on old-growth trees.

Connolly told The Narwhal that three areas representing some of the last relatively intact and unprotected areas of rare interior temperate rainforest exist near the Alberta border, in areas outside federal and provincial parks: the Walker Wilderness; the Raush Valley, and the Goat River Watershed that flows into the Fraser River in the Rocky Mountain Trench.

“Those are really important to protect because they function as lifeboats for biodiversity,” Connolly said. “We have landscapes here that are very fragmented.”

“People around the world and even British Columbians have an idea of what B.C. is — it’s pristine, it’s wild. The true reality is that essentially all of B.C.’s old-growth forest has been eliminated, and all you need to do is to look at this map to see that,” said Geoff Campbell of Pacific WIld.

Here’s what Sarah Cox at The Narwhal reported in February:

The map’s release comes as the B.C. government dawdles on a fall election promise to implement 14 recommendations made by an old-growth strategic review panel led by foresters Al Gorley and Garry Merkel.

Gorley and Merkel called for a paradigm shift, saying old forests have intrinsic value for all living things and should be managed for ecosystem health, not for timber supply. They also said many old forests are not renewable, countering the notion that old-growth trees can always grow back.

The two foresters recommended the B.C. government immediately defer development in old forests “where ecosystems are at very high and near-term risk of irreversible biodiversity loss.”

In response, in September 2020 the NDP minority government announced old-growth logging deferrals for two years in nine areas, totalling 353,000 hectares.

Ten days later, the government called a snap election and the BC NDP took out campaign ads saying it had “protected” 353,000 hectares of old-growth.

But mapping subsequently revealed that much of the deferral areas were already under some sort of protection, had already been logged or consisted of non-forested areas.

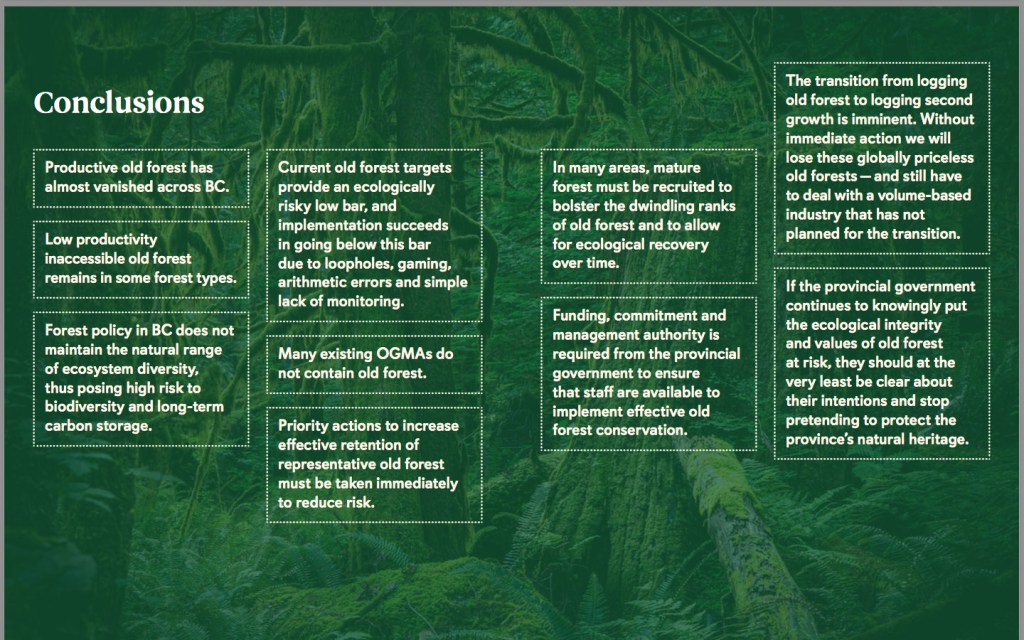

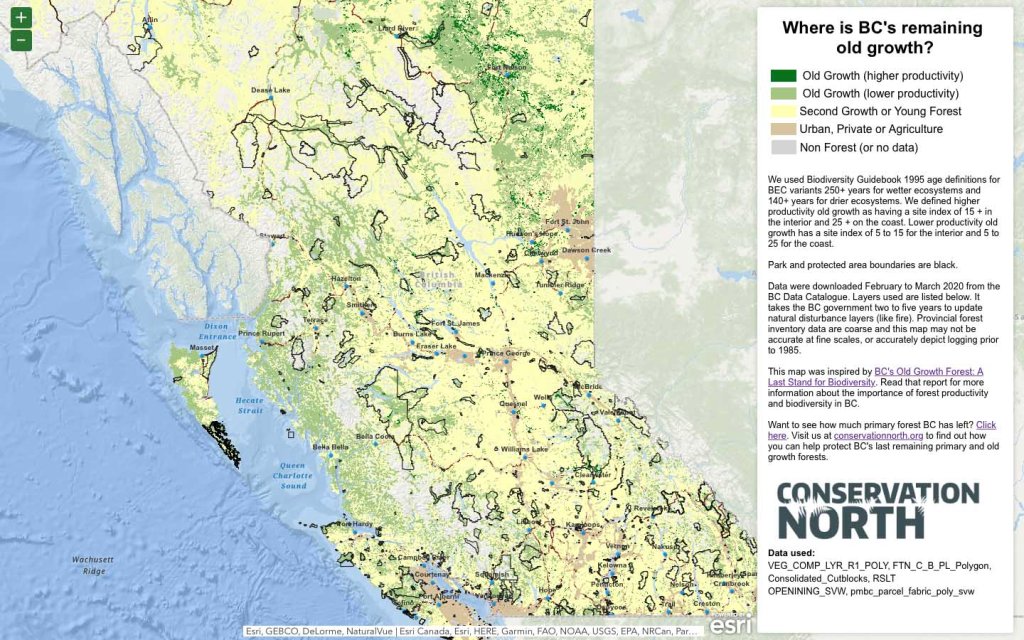

Scientists Karen Price, Rachel Holt and David Daust estimated that only about 3,800 hectares of B.C.’s remaining productive old-growth was included in the nine deferral areas. Price and her colleagues also found that only 415,000 hectares of productive old-growth forests are left in B.C. (around 1,600 square miles): centuries-old cedar and western hemlock inland rainforests that define biodiverse old-growth. This amounts to 1% of BC’s overall forests. This reality counters the government’s false assertion that 23% of the province’s standing forests were old-growth.

High productivity forests, where the biggest trees are found, contain the greatest biodiversity and are home to the most endangered species, such as mountain caribou, northern goshawk and fisher, a charismatic and reclusive member of the weasel family that, in B.C., dens only in five species of old trees.

Connolly said Conservation North wants people to be able to see where B.C.’s remaining old-growth is located. So, along with the Seeing Red map, the group also mapped the 415,000 hectares of productive old-growth identified by Price and her colleagues. This second map, titled “Where is B.C.’s Remaining Old-Growth?” clearly shows just how little productive old growth forest remains in British Columbia. These are the low valley big tree ecosystems of ancient trees with high biodiversity. According to the Price, Holt & Daust 2021 report, old-growth forests with big trees are rare; they require good growing conditions and little disturbance. Only 10% of the province supports this forest type. Of that 10% already 92% has been logged.

This leaves only 415,000 hectares of big tree old-growth. This amounts to three percent. I repeat, only 3%.

B.C.’s forestry practices came under renewed scrutiny when the Wilderness Committee discovered that the new NDP majority government had sanctioned logging and road-building in 157,000 hectares of second-growth forests in the deferral areas it claimed it had “protected.”

Wilderness Committee national campaign director Torrance Coste called the government’s suggestion that it had protected 353,000 hectares of old-growth “factually incorrect and incredibly misleading.”

The Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs has said it wants to work with the province to implement an old-growth strategy that will enable conservation financing and the expansion of Indigenous protected and conserved areas, while also allowing First Nations to pursue economic alternatives to old-growth forestry — including businesses in cultural and eco-tourism, clean energy and second-growth forestry.

Very recently, three First Nations called for deferrals to logging 1,150 hectares of old-growth forest in the Central Walbran region and 884 hectares of old growth in the Fairy Creek watershed near Port Renfrew by Western Forest Products and Teal Jones Group. The Fairy Creek watershed has been the site of blockades since August 2020 over a promised moratorium on logging of BC’s ancient forests, where over 1,000-year old yellow cedars live. Despite arrests, protesters maintained their stand at the blockades and were joined by many more. They gained immense support throughout Canada and worldwide with severe scrutiny on the BC government’s practices.

Actor Mark Ruffalo incited significant support with his call for action.

The NDP offices and other offices were flooded with letters, emails, and phone calls demanding consideration of the fourteen recommendations made by Price, Holt & Daust in their Old Growth Strategic Review (which the government had promised it would follow). A key recommendation was to immediately defer logging of remaining ancient forests in BC for at least two years and create a plan involving indigenous peoples for more sustainable forest management.

Then, despite having initially agreed to let the Teal Jones clearcut in their territory, the leaders of the Pacheedaht joined the Huu-ay-aht and Ditidaht to call for a deferral to logging the old-growth in the Fairy Creek and central Walbran Valley. The BC government has granted the First Nations’ request. Other First Nations in BC have requested logging deferrals and the premier said more will be coming this summer and over the next two years, as the province implements policies that acknowledge Indigenous rights and title.

Time to Be Honest

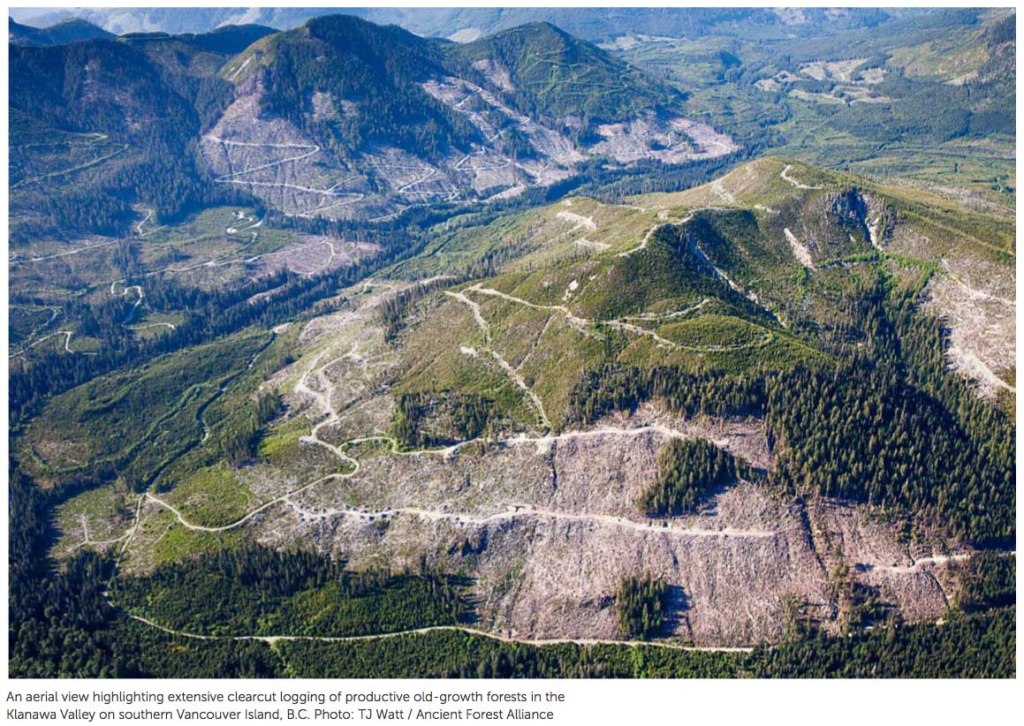

Sarah Cox describes how most people who have driven down B.C. highways have looked out the window at a screen of trees. It gives the false impression that British Columbia is a province rich in pristine untouched wilderness. I’ve driven up and down much of Vancouver Island. If you keep your eyes peeled you can just catch sight of what lurks behind that thin curtain (of trees). It’s not pretty.

“You can’t quite see what’s going on behind that strip of green but sometimes you’ll see a gap between the trees,” says Connolly. “These views that British Columbians get of our forests, both with our own eyes from the highway and via the messages that come out of industry and government, are carefully curated.” Connolly recalled taking a forestry course on how to conceal ugly industrialized landscapes from public view. “We called that course ‘lying with the landscape 101.” The Seeing Red map doesn’t hide anything, Connolly said. “It gives people a bird’s eye view.”

Go take a look—it will break your heart, but hopefully give you resolution.

I urge you to go to these last sites of old-growth forest. Walk through them. Feel their incredible energy. They are spectacular. I’ve witnessed both the cathedral-like majesty of intact old-growth and the heart-sinking devastation and despoiling by a clearcut. I saw Big Lonely Doug in a Teal Jones old growth clearcut just north of Port Renfrew far too close to the Gordon River. It made my heart ache with loss.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

One thing about forests is that they sop up water and hold the soil together. A mountain that has been denuded of trees is prone to landslides. Is that what happened when the rains came and the highways were inundated with rock and mud? A landscape that has been deforested can no longer act as a sponge. Is that what happened when the floods came?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It certainly is a key factor, Merridy …

LikeLike