Warsaw Caves Conservation Area is named for its cluster of seven caves in a rare old-growth hardwood forest off the Indian River near the village of Warsaw, Ontario. Formed thousands of years ago at the end of the last ice age, these cavities in the limestone rock have long passages and small open areas, wonderfully accessible to spelunkers.

When I first visited Warsaw Caves Park one late fall day, I totally missed the caves. My friend and I found the Lookout Trail and set out into mixed forest (white pine, cedar, fir, maple, and aspen), with a rich undergrowth of ferns and shrubs. We stepped carefully over large flat limestone slabs, many revealing the odd embedded crystalized fossil. In places, where footfalls were commonly made, the grey cement-looking rock had been polished into a burnished brown. In other places, large limestone boulders were piled into loose hills as though a giant had played a rolling game. In many places, we could hear the water gurgling below and felt a cool damp breeze issue from deep and dark cracks or openings.

Soon after entering the trail from the parking lot, we found a small path off the trail to what is called the Damselfly Pond. This is where the Indian River begins its flow underground for several hundred metres. When we returned here the following summer and had our lunch by the side of the water, we watched many black-winged damselflies, their wings whirring like tiny helicopters over the water and shore plants.

A few steps farther we crossed a small bridge over a tributary that spilled out into the same small bay of the Indian River. A picnic table sits on one limestone slab with a view of the Indian River before it disappears into the limestone karst. It’s a wonderful place to have lunch.

We continued on the trail up the hog’s back through pine and fir mixed forest. In some of the limestone slabs, we spotted small to large rounded depressions. These are called kettles, where a granite stone had embedded and ground itself into the softer limestone under the weight of the ice sheet.

On parts of the trail, we walked over a carpet of birch and poplar leaf corpses, already giving way to Nature’s decaying process to bring nutrients back to the forest. The birches, maples and poplars blazed in their fall dress to a remarkable view of the Indian River as it cut its way through the limestone valley below.

The Indian River

The Indian River starts at Stony Lake and flows southwest through the Warsaw Caves Conservation Area, where a short portion of it flows underground, through limestone karst formation. The Indian River then passes the community of Warsaw before flowing southward and eventually empties into Rice Lake, which flows via the Trent River into Lake Ontario. The river supports Largemouth bass, Smallmouth bass, and Walleye.

The trail up to the lookout took us about a half hour (more for my stops to photograph beautiful scenery and colourful leaves).

How the Caves Were Formed

The chief reason these caves exist lies in their limestone content. Limestone formation is the first step in the formation of these caves.

Limestone Formation

Limestone is a biological sedimentary rock formation composed mostly of calcite, a calcium carbonate mineral, and often resembles concrete. It forms as shells, corals, algae, fecal matter and other organic debris settle and accumulate on the bottom of a waterbody. Because of the conditions of its formation, limestone may hold fossils from a time long ago. According to Otonabee Conservation the limestone bedrock of the Warsaw area was laid down in the Paleozoic Era when shallow seas covered the region over 350 million years ago. Many organisms, from corals to microscopic foraminifera that grew shells from the carbonates in the water, contributed their carbonate shells when they died, accumulating in the sediments of the shallow seas. This sediment then lithified into limestone.

Geology.com writes that “cementation” is an important step in the transformation of a sediment into rock with precipitated calcium carbonate contributing as much as 50% and as little as a few percent of the rock by volume.

The calcium carbonate of the sea or freshwater may also crystallize out of solution during evaporation to form chemical limestones; but this process is more rare and not observed at Warsaw Caves. Evaporative limestones form the kind of caves most of us imagine when we think of caves. These form stalactites, stalagmites and other cave formations (often called “speleotherms”). Such caves are often huge and the limestone is known as “travertine,” a chemical sedimentary rock that can exist as “tufa,” at a hot spring or on the shoreline of a lake in an arid area.

Action of Glaciers

Millennia ago, a series of Pleistocene epoch glaciations, including the Wisconsin ice age, covered the Warsaw Caves area with ice sheets up to three kilometers. When the glaciers began their final retreat 12,000 years ago, meltwaters created Lake Algonquin (the present-day upper Great Lakes and Lake Simcoe) and Lake Iroquois (present-day Lake Ontario). The flow of glacial meltwater from the two lakes formed the Kirkfield Spillway, which included the Indian and Otonabee Rivers. Deep and swift, these glacier-fed rivers shaped the landscape, creating caves, kettles, limestone cliffs and ledges, and underground channels.

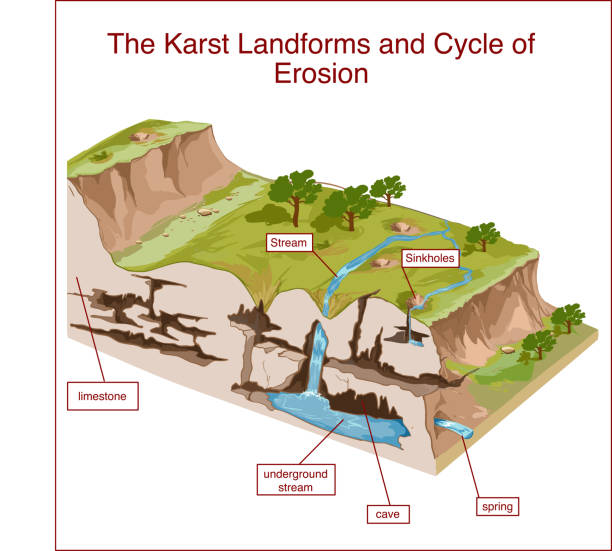

Limestone’s distinctive crystal structure allows it to crack and fracture in a distinct pattern. On limestone cliffs you can easily make out the horizontal cracks called ‘bedding planes’ and the vertical cracks called ‘joints.’ These allow water to easily flow through the limestone rock.The slightly acidic river that flowed over the bedrock made its way into and through these cracks, dissolving the limestone over thousands of years and widening the natural cracks and rock fissures in a process called carbonation. Over time a karst topography formed in the porous limestone at Warsaw Caves as water dissolved the limestone through a process called karstification. This created deep fissures and sinkholes, underground caves and streams. The word ‘karst’ comes from the pre-Indo-European language in which ‘kar’ means ‘rock.’ In Slovenia the word ‘kras,’ later Germanised as ‘karst,’ comes from the name of a barren stony limestone area near Trieste, which is still considered the type area for limestone karst.

As the glaciers retreated, the bedrock rose in an isostatic rebound. The shifting bedrock and continued erosion collapsed the underground river channels, leaving behind the current series of caves and broken limestone. A walk through this area reveals huge slabs of broken and collapsed limestone, piled in odd formations and all covered in moss and hemlock and cedar trees with adventurous roots that extend over them.

We spotted several kettles (rock potholes) in the limestone. These depressions were created when granite stones trapped in the river current were spun around in place, grinding their way into the underlying limestone.

A string of seven limestone caves can be explored in the Warsaw Caves park. The following year, one summer day, we went back and this time visited the caves. The caves are accessed by squeezing into narrow crevices and sometimes crawling on hands and knees. All are cool, fairly damp, and small; some are quite cramped. There’s even an ice cave, where you might find ice even in hot summer weather. Be prepared to get dirty and do some crawling and climbing. It’s best to wear a spelunker’s headlamp, but you don’t really need to. In virtually all the caves, sufficient light enters to make your way about safely.

After our spelunking, we drove to the small village of Warsaw and had ice cream, a fine reward to a good adventure.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

One thought on “Spelunking in Warsaw Caves”