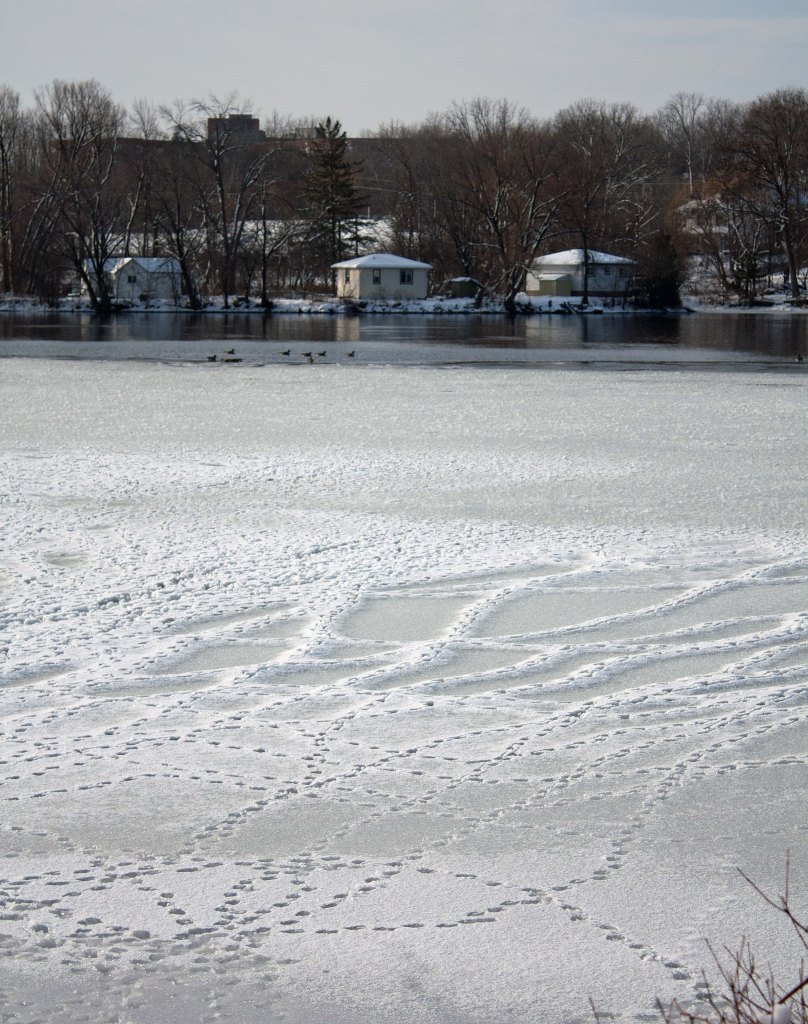

During my daily walks in the deep snows of winter here in the Kawarthas of Ontario, I’m often delighted to find signs of animals. Tracks by squirrels, rabbits, ducks, other birds, mice and voles and even fox. I see them track across the ice on the marsh or the river shore, or over a fresh snowfall in the riparian forest and thickets and meadows. It doesn’t matter how cold the day or night is, those tracks still come and go. I’m talking about temperatures ranging from zero Centigrade to minus thirty!

Adaptations to Winter

It’s times like these, as I walk all bundled up in my winter boots, winter coat, scarf, merino wool hat and hood, that I think about how these creatures survive the cold winter. Wildlife biologists tell me that three main strategies are used by the creatures of the north during winter to survive the cold: migrate, hibernate, and insulate.

Most of us are familiar with the migration of song birds, noting their arrival in spring with their welcome songs. The American robin and its other thrush relatives with their ethereal fluting songs are a moniker of spring for me.

But what of the creatures who remain as the snows come and the bitter cold sweeps over the land with a relentless wind? Of course, one strategy for these animals is that they fatten up with oil-rich seeds and nuts and grow extra thick fur in response to the cold; both of these help with insulation. I’ve noticed that the local black and grey squirrels started looking rather plump already by early winter. Many even grow tufts on their ears, resembling the European red squirrel.

Eric Wagner of the National Wildlife Federation writes that grouse and ptarmigan “plunge into snow on especially frigid nights to stay warm. And larger mammals, from porcupines to wolverines to bears, dig dens in snow for resting between bouts of foraging, raising families or hibernating during winter’s duration.”

The ‘Thermal Blanket’ of The Subnivean Zone

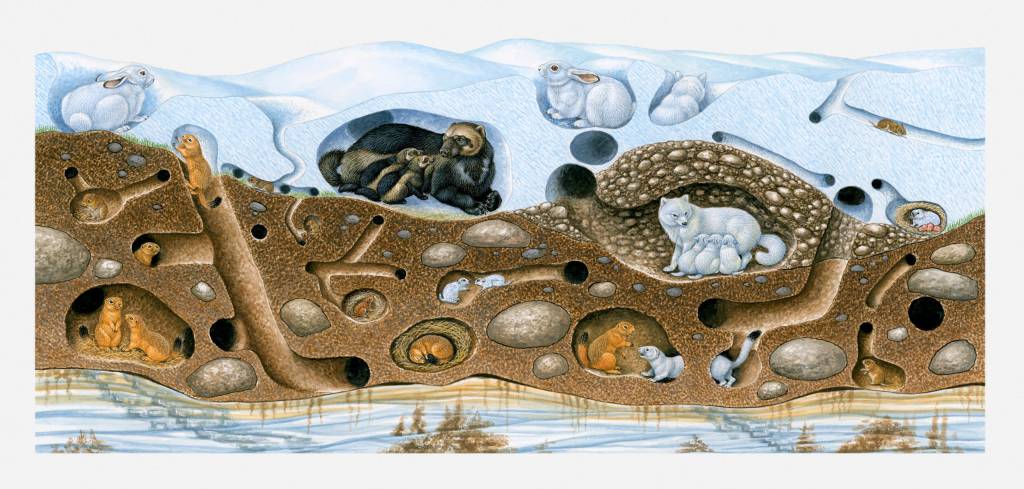

But another way for animals to avoid bitter cold winds, predators, and starvation is by using the subnivean zone—a snow layer that begins to form after the first lingering snowfall. The blanket of snow on the ground traps some of the heat that rises out of the earth; the heat melts just the bottom layer of snow, creating a pocket of air just right for tiny creatures to burrow and build tunnels underneath it. Freshly fallen snow has the best insulating properties; over time these properties decrease as air spaces between snowflakes disappear.

The subnivean zone includes the area between the surface of the ground and the bottom of the snowpack. The term comes from the Latin “sub” (under) and ‘nives (snow). He Inuit call it pukak. The subnivean zone is the sanctuary retreat of red squirrels, chipmunks, mice, voles and shrews during the winter. Rabbits and foxes that also use burrows would use the subnivean zone. These creatures create long and elaborate tunnel systems with air shafts that ventilate and create escape routes to the surface, sleeping areas, meal hubs with food caches, and even latrines.

On my walks through snow-covered meadows and thickets I’ve noticed the tiny tracks winding along like rope that led to a small hole in the snow: an entrance—probably an air vent—into some little creature’s subnivean home. Alerted, I also spotted some near-surface tunnels that had created small humps in the smooth snow surface.

Cecilia Vigil and Megan Lahti of the Reno Gazette Journal describe the process of subnivean zone development this way:

First, the snow that lands directly on hardy vegetation and overhanging rocks is blocked from accumulating underneath. The snow’s weight causes the plant branches found here to droop to the ground, creating umbrella-like structures ideal for tunnels. Second, some of the ground snow will sublimate, meaning that it changes from a solid to a gas without going through the melting stage. Sublimation creates a roof as the heat from the earth melts the snow into vapor. If you are thinking this sounds like the Inuit igloos, then you would be correct! The tiny spaces between snowflakes and ice crystals trap heat from the earth. This is a fundamental principle of most insulation, and why fur and hair are terrific insulators for larger animals, and why your down jacket keeps you warm.

Air shafts, which provide necessary oxygen, are naturally created by plant stems, grasses, tree trunks and burrowing insects (all of which double as a food sources). Because light can filter through several feet of snow, plants close to the ground and buried beneath a layer of snow can continue to photosynthesize and grow. When the snow achieves a certain depth—usually over eight inches—the temperature will remain close to zero degrees.

Joanne Stolen at Summit Daily tells us that the subnivean climate is formed by three types of snow stages or metaphorphoses: destructive, constructive, and melt metamorphosis. All three types transform individual snowflakes into ice crystals and create spaces under the snow where small animals can move. Destructive metamorphosis begins as the snow falls to the ground: often melting, refreezing and settling. The melting snowflakes fuse with others around them, becoming larger until uniform in size. This stage occurs most rapidly during larger temperature extremes such as warm days followed by cold nights. As the snow settles and compacts air spaces, it reduces the penetration of the sun’s heat. Constructive metamorphosis is caused by the upward movement of water vapor in the snowpack. When the water vapor reaches the top of the snowpack and meets much colder air, it condenses and refreezes and the ice crystals at the top form a crust. Melt metamorphosis causes snow deterioration by melting, increased by warmer temperatures, rain and fog. As snow melts, water moves downward, refreezing and thickening the middle of the snowpack. During this refreezing heat is released and, as more water comes down from the surface, more heat is created, bringing the whole snowpack to near equal temperature. This process bonds the snow and strengthens the snowpack and the subnivean zone.

While living under the snow helps against the cold and starvation, predation still occurs. Hawks, owls, coyotes and foxes can all hear or smell mice and voles running from several metres away. Foxes will dive head-first into the snow to catch their tunneling prey.

As spring arrives, these subnivean animals—alerted by awakening dormant roots and shoots—abandon their winter sanctuary before ice and snow thaw and rain fills or collapses their tunnels.

Risk from Climate Change

Wagner warns that “snow cover has declined throughout the Northern Hemisphere since 1970. Snow also has started to melt earlier in the year, moving the period of greatest snow cover from February to January. Scientists in Europe predict that the number of days with snow will have decreased by up to 80 percent at the end of the 21st century.”

What does this mean for the subnivean zone?

“Counterintuitively, warmer winters do not necessarily lead to warmer temperatures for creatures of the subnivean. As winter temperatures increase, Pauli says, “the snowpack will be reduced, and snow density will increase.” Because warm air holds more moisture, snow—instead of being dry and fluffy—will become wet, dense and colder. Warmer temperatures lead to a chillier subnivean… Plants subjected to more frequent freezing and thawing could suffer significant tissue damage. For small mammals such as shrews and voles, temperatures that are both colder and more variable could also be bad news.”

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.