It started after several days of warm spring rains. It was still very damp out as I took the old rutted gravel road to one of my favourite maple-beech forests located on an old drumlin in Ontario.

.

.

As soon as I stepped onto the gravel road, I spotted what looked like a pile of wet sloppy greenish-brown dog poo. I stepped over to the other road track and saw more of the slimy stuff. My first thought was “this poor dog has the runs!”; but when I spotted a long trail of this stuff over the gravel, my mind quickly amended. Time to check more closely. I bent down and, after gingerly touching its firm jelly-like surface, I realized that this was not poo at all. It was some kind of organism.

.

I picked it up, feeling its rubbery cool surface. My first thought was that it was some kind of slime mold or jelly fungus; they come in all colours, including brown with a firm jelly-like texture. I’d previously identified a black jelly fungus called Black Witch’s Butter (Exidia glandulosa) in another maple-beech forest in spring.

But the organism I was looking at on the ground somehow eluded identification; it had a “seaweed” look and texture to it. After a brief visit to my friend “Google” I solved the mystery: this was a cyanobacteria, specifically Nostoc commune.

.

Naming the “Poo” (Nostoc commune)

Nostoc commune is a cyanobacteria and part of a large genus (belonging to the family, Nostocaceae). Cyanobacteria were previously diagnosed (and by many still referred to) as blue-green algae because their blue-green photosynthetic pigments produce polysaccharides and generate oxygen like other algae). What distinguishes cyanobacteria from algae is they lack membrane-bound nuclei, making them prokaryotes, not eukaryotes with membrane-wrapped nuclei like all algae, and their photosynthesizing pigments are scattered loosely in the cell’s cytoplasm, not organized within chloroplasts as with algae.

.

.

Identifying Nostoc commune is a challenge, given its distinctly different forms that depend on its state of hydration. In wet weather, the organism may resemble a slimy aggregate; after a day or two of dry sunny weather, it will collapse, blacken and harden into a thin friable film that easily crumbles. Nostoc commune continues to live in its dehydrated state and will easily rehydrate with added water. I tried this with a dried out brittle ‘wafer’ and within an hour the polysaccharide matrix swelled as it rehydrated to its original globular state.

.

.

Nostoc commune appears to have many common names. It is called mare’s eggs, Táak-chak (‘rain-poop’ in Mayan) and facai (in China). Nostoc commune has also been called ‘witch’s butter’ like the jelly fungus (Tremella mesenterica). Joe Boggs at Buckeye Yard & Garden onLine of Ohio State University shares how the alien-looking and sudden appearance after a thunderstorm of hydrated Nostoc commune resulted in some strange names such as ‘star-jelly’, ‘star-shot’, and ‘star-slime’. According to the University of Florida, N. commune may also be called ‘ground boogers’ and ‘dragon’s snot’.

According to Malcolm Potts, In Germany during the Middle Ages the rapid appearance of growths of N. commune after thunder showers led to the common belief that such colonies fell from the sky, and these growths were referred to as Sternschnuppen (shooting stars).

“The word Nostoch was invented by colourful 15th century scientist, philosopher, and alchemist Aureolus Philippus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (Paracelsus) to describe the gelatinous colonies of the ubiquitous terrestrial cyanobacterium Nostoc commune. It is proposed that Nostoch is a play on two words, an Old English word and a German word, with both describing that part of the human anatomy intimately associated with extracellular polysaccharide; Nosthryl and Nasenloch = Nostoch.”

Malcolm Potts

.

Ecology & Adaptations of Nostoc commune

Nostoc commune is part of a large genus (belonging to the family, Nostocaceae) that is usually associated with often nutrient-poor freshwater habitats. Nostoc commune is particularly suited to live in the harsh terrestrial environments with extended drought or freezing.

.

Nostoc commune typically lives on the ground, on bare soil, pavement, and gravel surfaces, where I found it. When it rains, Nostoc commune revives from its insconspicuous dormant stage—patches of blackened, brittle crusts—to form dark blue-green or olive-green lumpy globular masses that may resemble a colony of tiny seaweeds.

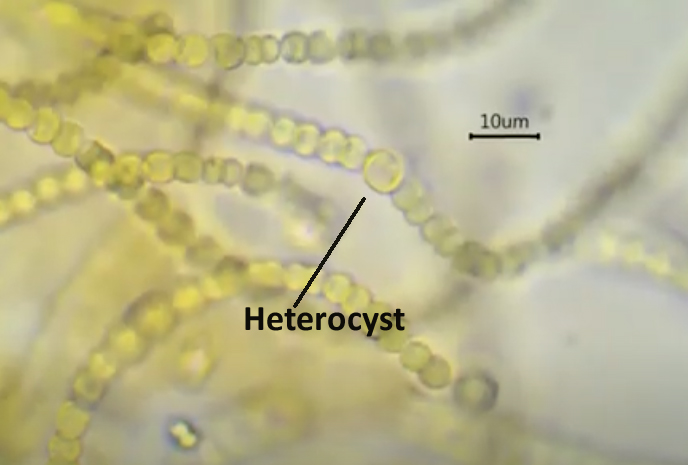

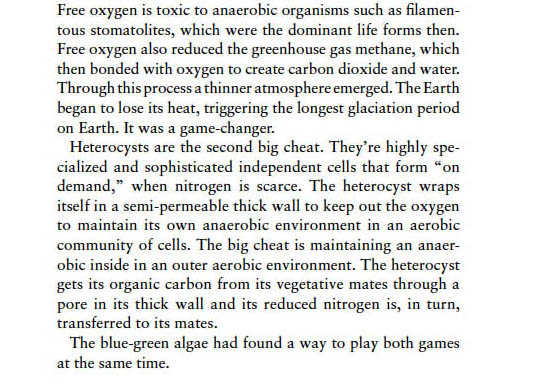

This single-celled organism exists in a multicellular state through chains of connected cells or filaments, which allow cells of N. commune to communicate and share nutrients. Each filament is covered in a mucilaginous sheath and embedded in a gelatinous matrix of polysaccharides to help it resist environmental stresses. The polysaccharides—of which 70% are glucose—include nine monosaccharides, uronic acid, deoxy-sugars, pyruvate, acetate, and peptides. Nostoc spp. also use specialized cells called heterocysts that can grab nitrogen from the air (called nitrogen fixation) to help them and associated plants grow.

.

.

Nostoc commune is considered an extremophile by some biologists, given that its desiccated colony can resist heat and repeated patterns of freezing and thawing and produces no oxygen while dormant. Li and Guo report that the desiccated N. commune can remain viable for more than 100 years. N. commune can thrive under intense solar radiation through specialized pigments that absorb UV light to protect against UV radiation. Nostoc commune is also able to survive severe dehydration through several polymers that keep its overall structure intact. It may also form akinetes (a type of spore) resistant to extreme conditions and short motile filaments (hormogonia), fractions of filament produced by vegetative reproduction that detach and reproduce by cell division—considered ‘escape units’ to promote survival. These adaptations have allowed this cosmopolitan cyanobacterium to thrive worldwide and in some of the most extreme environmental conditions.

Alberto Melappioni provides a good summary video and microscopic description of Nostoc commune, which looks like an aggregation of long twisting strands of beads in a mucilaginous sea.

.

.

Toxicity of Nostoc commune

Nostoc commune is not toxic to plants or animals.

Several aquatic benthic species of Nostoc are known to produce toxic and allelopathic compounds in lakes, streams and rivers. These biologically active secondary metabolites are produced in response to environmental stress. Toxins released into the water may include microcystins (liver toxin), lipopolysaccharides (skin irritants), and BMAA (beta-methylamino-L-alanine; nerve toxin) when the cell wall is disrupted (cell lysis) after a bloom or when under other stresses.

.

.

Eating Nostoc commune

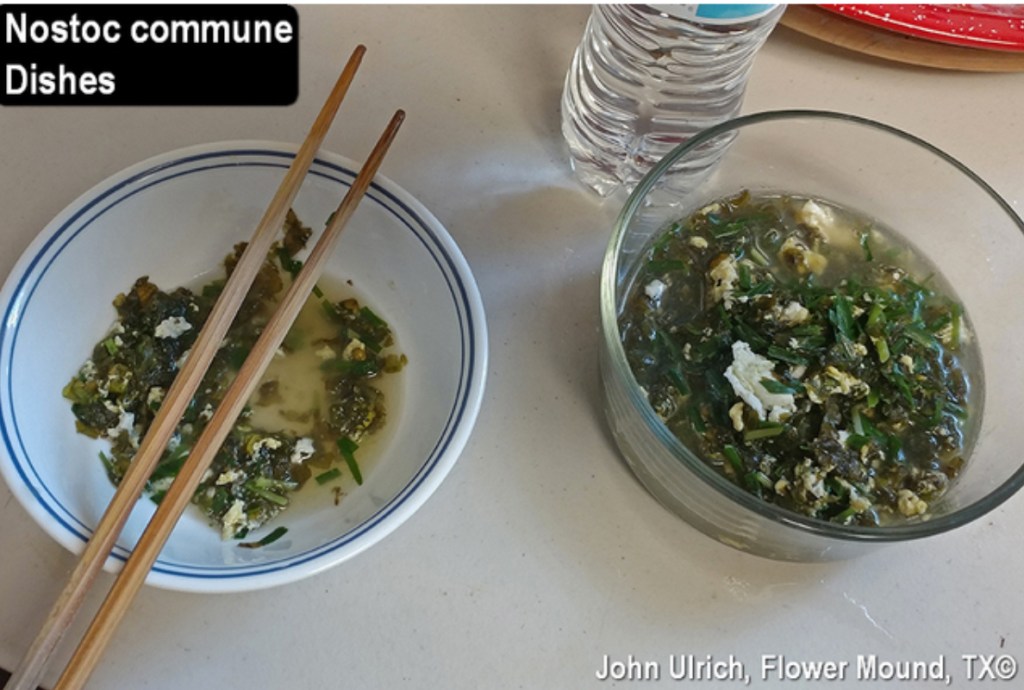

Nostoc commune has long been appreciated worldwide as a healthy food and traditional medicine. It is commonly eaten in many Asian countries (e.g. Philippines as a salad, Indonesia, Japan, and China). According to Li and Guo, N. commune possesses a wide range of “remarkably protective physiological and pharmacological” properties such as antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic and immune regulation properties.

Joe Boggs shares some dishes by colleague John Ulrich, including soups, salads, a Chinese dish called Facai (traditionally served at the Lunar New Year) and a scrambled egg dish.

.

.

How Cyanobacteria Already DID Take Over the World

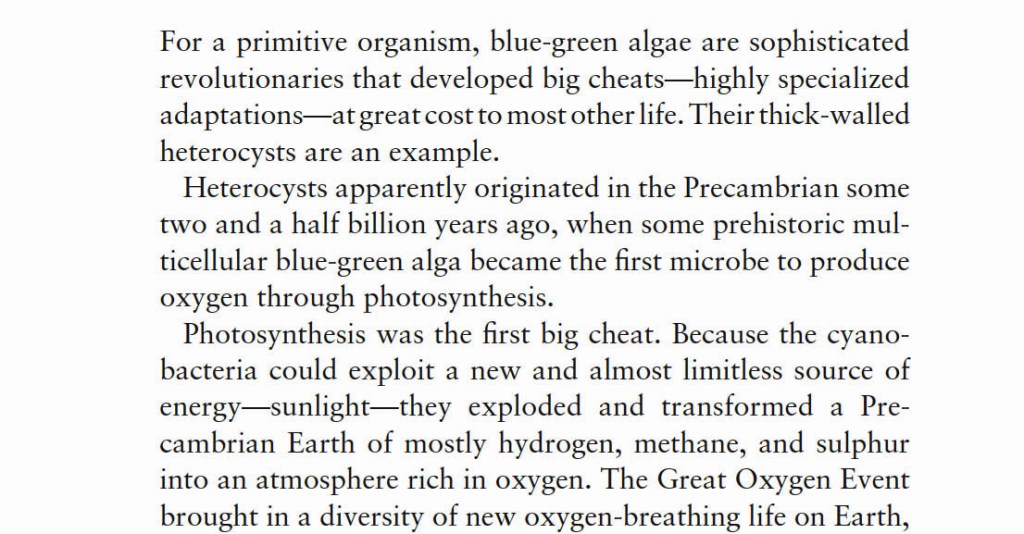

Around 2.45 billion years ago a rapid change in the Earth’s atmosphere from anaerobic to aerobic occurred. Referred to as the Great Oxygenation Event (GOE), it caused one of the greatest extinction events in Earth’s turbulent evolution (wiping out most life, which was anaerobic); it also heralded the emergence of aerobic metabolism and ultimately of multicellularity.

Cyanobacteria were implicated as the main oxygen-producing organisms that pushed atmospheric oxygen towards the current 21% it is today.

In my eco-fiction novel A Diary in the Age of Water the diarist, a cynical limnologist, describes the two “big cheats” of cyanobacteria (blue green algae)—of playing both sides—to dominate the world:

.

.

References:

Hata, Shingo et al. 2022. “Dried Nostoc commune exhibits nitrogen-fixing activity using glucose under dark conditions after rehydration.” Plant Signal Behav. 17(1): 2059251.

Li, Zhuoyu and Min Guo. 2018. “Healthy efficacy of Nostoc commune.” Oncotarget 9(18): 14669-14679.

Potts, Malcolm. 1997. “Etymology of the Genus Name Nostoc (Cyanobacteria).” International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, April, p. 584.

.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna .Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

It’s been many decades since I studied high school biology, and when I did, it did not impress me. Sure wish I had found someone like you years ago who makes learning fun studying a billion year old double dealing organism. Can’t wait to share this article with my lab mates!

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed it. Funny… I had the very same experience you had with high school biology. In fact, I quit the course and took typing (I felt a much more useful course) instead. Then, when my priorities changed, and I realized I needed biology to enter university in the sciences, I challenged the exam and did all right (just used the text book). Best, Nina

LikeLike