“[Mosses] are the most overlooked plants on the planet. But they’re gifts, too. They provide us with another model of how we might live.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer

Soon after I moved to Peterborough to escape the soul-ravaging tumult of Toronto, I discovered Jackson Creek Park. A natural gem embedded right in this small city. The creek flows through an old-growth mixed forest dominated by large White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis), White Pine (Pinus strobus), and Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga Canadensis). The conifers are mixed with significantly large deciduous trees such as white ash, sugar maple, American beech, yellow birch, red oak, black walnut, bitternut, and American hophornbeam (Ostrya virginiana). White pines up to 34 m high form a super-canopy over the giant cedars and hemlocks, themselves no slouch. Trees over one hundred and fifty years old are common and several are over 250 years old, predating the settlement of Peterborough. Old-growth characteristics are evident in the pit and mound topography, coarse woody debris and nursing logs, large old trees (almost one in five trees with 50 cm or greater diameter; trees > 150 years old common), super-canopy trees, and wildlife use such as the common Pileated Woodpecker feeding cavities.

Peterborough is one of only eight cities in Ontario with an identified remnant old-growth forest within its urban core and the Jackson Creek old-growth forest is the fourth oldest of Ontario’s identified old-growth forests.

My initial walk through this riparian forest led me down a steep narrow path off the major trail into the gorge of Jackson Creek to its south (right) bank. At this point, the creek flows mostly west to east before bending to flow south. The creek is fairly wide in places and flows along rapids and glades through glacial till.

I followed a narrow ‘deer’ trail that hugged the right bank of the river, through mostly cedar trees, ferns, litter and moss. This lower trail by the river, though fairly well used by hikers and dog-walkers, is not marked on any of the park maps, which focus on the main trails that are groomed for easy walking. This trail, by contrast, weaves along the river over gnarled cedar roots, over stray rocks strewn willy-nilly, and damp puddles of squelchy humus. On many subsequent trips to this park, I would find treasures of fungi hiding in plain sight throughout the forest.

Aside from the obvious red and black squirrels and birdlife, signs of wildlife abound everywhere. On one winter walk through this forest, I spotted fox tracks in the snow and on a early December hike, I found a fox skull on the bank of the river in a small cove.

Another time, I spotted an otter swimming in the river. Blue jays are active in this old-growth forest, their aggressive call echoing throughout the damp forest. And the prehistoric shriek of the pileated woodpecker can be heard frequently. I once spotted a pair sitting quietly on a hemlock branch by the main trail. Wookpecker holes can be seen everywhere.

Moss Country

This is moss country. Mosses are everywhere. Literally. They live on the forest floor, pushing up under the leaf litter; they live on rocks and boulders, old decaying logs, snags and living trees, old and young. They are a rainforest in miniature, which have inhabited the Earth for over 400 million years and having endured every climate change that has occurred. They can grow in places other plants cannot.

On one drizzly day in spring, I stopped by a particularly bright tuft of star-like moss at about my height on a fairly young poplar tree. I later identified it as Orthotrichum sordidum, a pioneer moss species that colonizes young trees.

Moss expert Jerry Jenkins vividly describes the process of moss adaptation with tree growth and age:

“Young trees, with small crowns and tight bark, have limited stem flow and storage. They are colonized by a relatively small group of pioneer species that make thin mats and small dense tufts. As the crown increases and the bark roughens, storage and flow increase, and the pioneers are supplemented by species that make fringes and saggy mats on the trunk and thick stockings covering the base. In big old trees, the fringes and mats may extend high into the crown, and the tree base accumulates soil and becomes an extension of the forest floor.”

“It seems as if the entire forest is stitched together with threads of moss. Sometimes as a subtle background weave and sometimes with a striking ribbon of colour, a brilliant fern green. The ferns which decorate the trunks and branches of the old-growth trees are never rooted in bare bark, always in moss. Ferns give thanks for mosses…Towering trees and tiny mosses have an enduring relationship that starts at birth. Moss matts often serve as nurseries for infant trees.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gathering Moss

The Creation of Jackson Creek Valley

After descending into the stream’s valley, my walk upstream took me through mostly cedar swamp forest littered with bright green boulder erratics: moss-covered limestone or granite boulders, no larger than a coffee table, scattered among the tall trees. Granite is considered a coarse-grained igneous acid rock, a plutonic rock formed from magma that slowly cooled and solidified underground.

When the glaciers retreated north, creating the proglacial lakes and meltwater channels (e.g. the Schomberg Ponds and Lake Iroquois where Peterborough is currently), they left the rocks they scoured and carried behind. The Jackson Creek valley was formed by the torrent of glacial meltwater flowing from the ancient Lakes Algonquin and Jackson through the overlying till to create a glacial spillway approximately 12,000 years ago. At the location of the Jackson Creek old-growth forest, near where Monaghan Road meets Parkhill, the spillway slopes steeply, rising some 25 metres above the Creek. The north-east facing slopes and valley bottom provide ecological conditions that favour White Cedar and Eastern Hemlock. These slopes have also discouraged land clearing and development, allowing an old- growth forest to persist here on the hilltop, slopes, and valley bottom.

As I walked upstream along the river’s right (south) bank, which sloped more steeply now, my attention was caught by a singularly large slightly pyramid-shaped granite boulder—one of several glacial erratic boulders that litter this forest. Aside from being covered in several different mosses, the rock itself was a beautiful mosaic of pink rock and jeweled crystals of coarse-grained quartz and feldspar. I caught glints of mica amid darker coloured minerals.

Behind the large boulder, to the west and in the upstream direction of Jackson Creek, stood an ancient beech tree snag with young juveniles growing beside it.

Altogether, the sight was rather magnificent and I remember standing there in stunned rapture. This became a destination for me and the boulder soon became “Nina’s Boulder;” to study over the many seasons I visited.

Nina’s Boulder

Nina’s Boulder stands on a moderately steep slope, among smaller moss-covered glacial erratics and tall cedar trees, just meters from the right bank of Jackson Creek. This is a mesic forest, one that receives a well-balanced supply of moisture throughout the gowing season (about 120-150 cm annual rainfall).

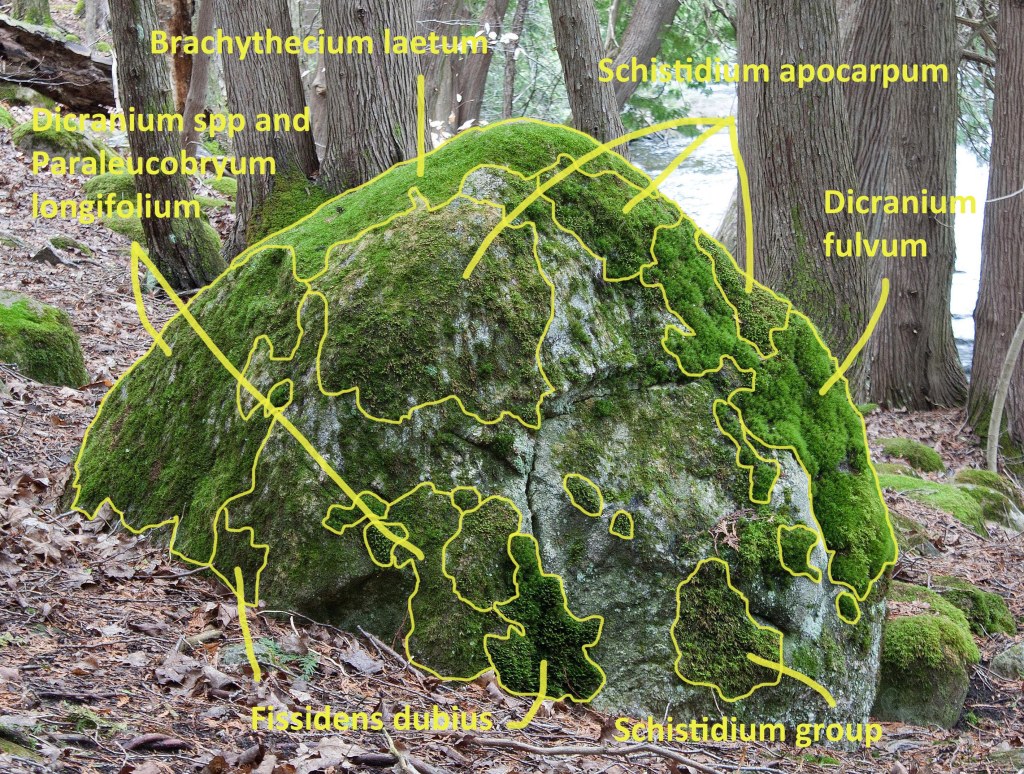

Nina’s Boulder measures about 84 cm high to its pyramid-peak and just over 110 cm wide on its east face; the major horizontal fissure on the east face of the boulder is located more or less halfway at 48 cm from the ground. The boulder is covered in a patchwork thatch of mosses year-round and supports a diverse number of them, all adapted to the boulder’s relationship with humidity, water retention, wind, and organic material (e.g. leaf and litter fall). Jenkins writes that “boulders receive most of their water from humidity and rain. When they are in the open or in dry woods, they are among the driest of habitats.”

“Boulders are coupled to the surrounding forest by through-fall, litter-fall, and ground-layer humidity. The wetter the forest, the wetter and dirtier the boulder. In mesic forests with closed canopies [such as the one in Jackson Creek], soil accumulates on top of the boulders and thick-mat species like the Brachytheciums and tall grove-forming species like the … Dicranums dominate. Dicranum fulvum expands to make thick, continuous mats; the Plagiotheciums, which specialize in flow interception, become common on the sides. Humidity-requiring species like Thuidium and Plagiomnium from the forest floor colonize the lower sides.”

Jerry Jenkins

What Jenkins describes is also what I observed on Nina’s Boulder.

Brachythecium laetum (a very common woodland moss) colonized the top of the boulder, with Schistidium apocarpum and Dicranum (probably D. scoparium or D. montanum) below it.

Further down the boulder, a mixture of Dicranum fulvum (one of the most common dry rock mosses) and Paraleucobryum longifolium (another common moss on boulders) colonized the vertical faces of the boulder.

Near the bottom of the boulder, mostly on its east face, I found the leafy Fissidens dubius, very common on moist soil and rocks and in the splash zone of streams. On the boulder’s bottom north face—the side facing the creek—a mixture of Plagiomnium cuspidatum, Fissidens dubius, and Rhodobryum were thriving.

“The rocks are beyond slow, beyond strong, and yet yielding to a soft green breath as powerful as a glacier, the mosses wearing away their surfaces, grain by grain bringing them slowly back to sand. There is an ancient conversation going on between mosses and rocks, poetry to be sure. About light and shadow and the drift of continents … The material and the spiritual live together here.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gathering Moss

I will continue to visit and meditate by Nina’s Boulder and I will fine-tune my identifications with further confirmations. I highly recommend the photo guidebook by Jerry Jenkins.

References:

Adams, P and C. Taylor. 2009. “Peterborough and the Kawarthas” 3rd edition. Geography Department, Trent University, Peterborough, ON. 252pp.

Henry, Michael, Peter Quinby and Michael McMurtry. 2016. “The Jackson Creek Old-Growth Forest.” Research Report No. 33, Ancient Forest Exploration & Research.

Hewitt, D.F. 1988. “Geology and Scenery: Peterborough, Bancroft and Madoc Area.” Geological Guidebook No. 3 (Reprint), Ontario Department of Mines. 114pp.

Jenkins, Jerry. 2020. “Mosses of the Northern Forest: A Photographic Guide.” Comstock Publishing Associates, Cornell University Press, Ithaca. 169pp.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 1992. “Gathering Moss.” Oregon State University Press, Corvallis. 168pp.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

2 thoughts on “Moss—A Study of ‘Nina’s Boulder’ in Jackson Creek Old-Growth Forest”