I don’t call myself a treasure hunter. But I am an explorer; I look for a ‘treasure’ of sorts, I suppose: the treasure of discovering something new. So on that day in May, I set out to explore new territory. I decided to drive north from Peterborough on Haliburton County road 507, as far as it went, which was the small hamlet of Gooderham in Highlands East. The village is essentially several houses and shops, a church, community centre and diner clustered around where Highway 507 meets H503 and ends. And where a prize awaited me…

Driving the Canadian Shield & the Bancroft Shear Zone

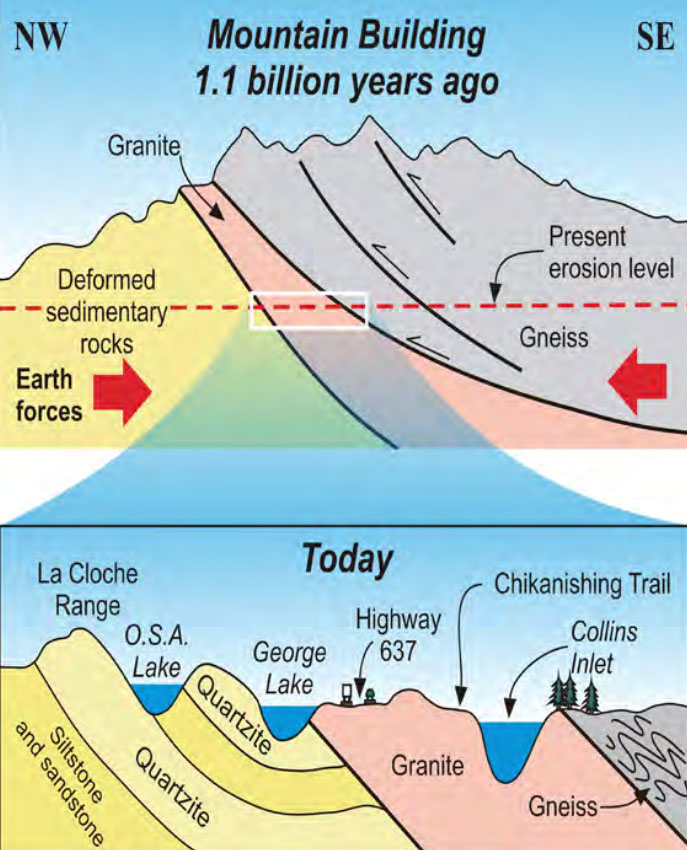

My drive to Gooderham took me over the Canadian Shield—an area of ancient Precambrian igneous and high-grade metamorphic rocks that formed over 3 billion years ago through glaciation, erosion and plate tectonics (movement and collision of the Earth’s outer crustal plates). In a process called “orogeny”, collisions of this jigsaw puzzle of crustal blocks (known as “provinces”) squeezed and welded rock together, deforming them and metamorphosing them and creating a belt of younger rock where the blocks collided. The huge pressures thrust the plates upward, creating huge mountain ranges. One of the largest was the Grenville Orogeny, which created mountain ranges at least as high as the Himalayas called the Grenville Mountains. Spanning from Quebec through Ontario and down the eastern side to Texas, the Grenville Mountains were possibly the largest mountain range created on Earth. A combination of erosion and glaciation then wore down these ancient mountains.

Over millennia, wind and rain eroded and wore down these mountains to their roots, estimated at some tens of kilometers of rock. The weathering was interrupted by ice ages spanning over two million years. The giant Laurentide ice Sheet (up to 3 km thick), which covered most of Canada multiple times during the Quaternary glacial epochs from 2.5 million years ago to the present, stripped off what remained of the overlying rock and deposited sediment south. Ice sheets advanced and melted back many times as sand, mud and stones that were lodged at the base of the ice scratched and ground the mountains down; the moving ice polished and sculpted the rock surface below and transported erratic boulders south to litter southern Ontario’s later forests.

The Canadian Shield is the largest area of exposed Archean rock with base rocks having been repeatedly uplifted and eroded.

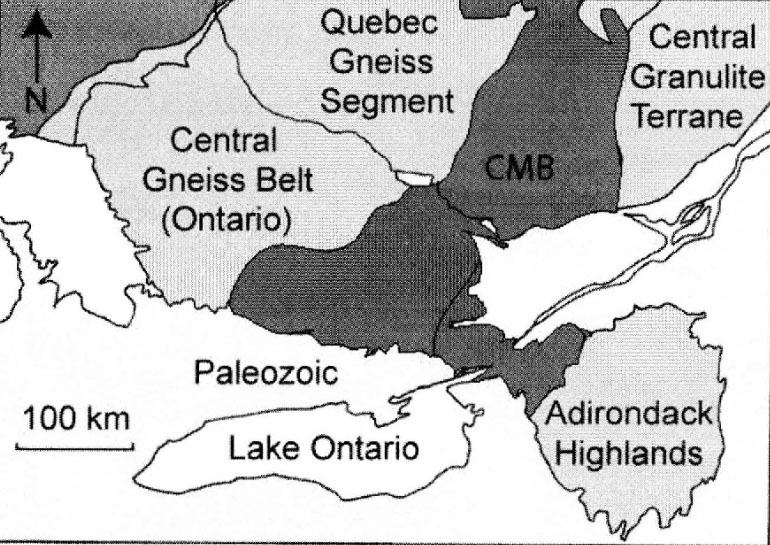

Country Road 507 took me through what geologists call the Central Metasedimentary belt (CMB) of the Grenville province, formed between 1.3 billion years to about 980 million years ago during the Grenville orogeny.

According to Heidi Daxberger at UofT, the Central Metasedimentary belt is made up of highly deformed and metamorphosed carbonate rocks, representing the former ocean floor sediments. According to R.M. Easton (2012), Pencil, Catchacoma and Mississauga Lakes east of the 507 drain south along the Mississauga River into Lower Buckhorn Lake, which is part of the Trent-Severn drainage system: “The sinuous Trent-Severn River system roughly corresponds to the boundary between the flat-lying Paleozoic rocks to the south and the crystalline rocks of the Precambrian Shield to the north.”

Country Road 507 also crosses the Bancroft shear zone, just south of Gooderham, which separates the land into two lithologic zones: 1) a zone of calcite and dolomite marbles, silicate marbles, breccia with marble matrix, and skarn; 2) a zone of metagabbro, pyroxenite, and amphibolite. Check out the meandering thickened heavy lines that cross Highway 507 twice just below the “G” for Gooderham on Figure 1, below.

Here’s how Wikipedia describes a shear zone: “In geology, a shear zone is a thin zone within the Earth’s crust or upper mantle that has been strongly deformed, due to the walls of rock on either side of the zone slipping past each other. In the upper crust, where rock is brittle, the shear zone takes the form of a fracture called a fault [see Figure 2]. In the lower crust and mantle, the extreme conditions of pressure and temperature make the rock ductile [Figure 2]. That is, the rock is capable of slowly deforming without fracture, like hot metal being worked by a blacksmith. Here the shear zone is a wider zone, in which the ductile rock has slowly flowed to accommodate the relative motion of the rock walls on either side.”

The Bancroft shear zone (see Figure 1) is located in the western portion of the CMB and separates middle to upper amphibolite-grade gneisses and marbles of the Bancroft domain from overlying greenschist to lower amphibolite-grade gneisses, metavolcanics and marbles of the Elzevir domain. The Bancroft shear zone is a narrow, anastomosing belt of mostly mylonitic marbles. The thickness of the zone is less than 20 m with an overall width of less than 2 km. Wide-spread thrusting coincides with extension and scientists speculate that this reflects the gravitational collapse of an over-thickened orogenic wedge.

The Bancroft Shear Zone & Marble Mylonites

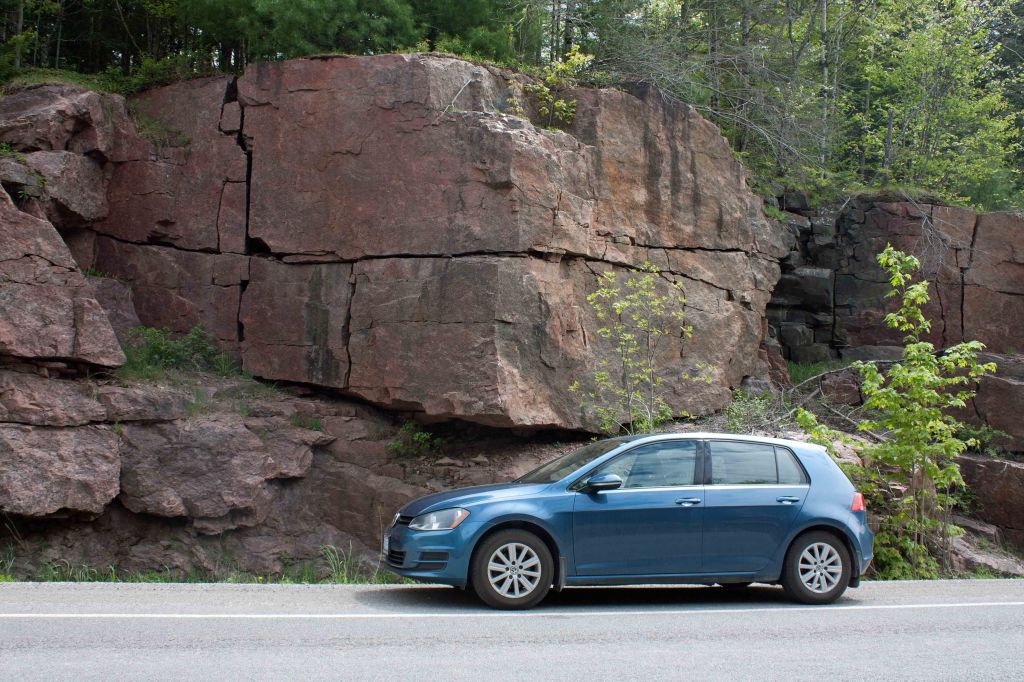

Just as the local geology showed stunning examples of folding, stretching and rotating, the highway I was driving meandered up and down, and wound and circled past huge granite and limestone outcrops and road cuts, through a varying mosaic of old-growth hemlock forested hills, dystrophic lakes, steep gorges, paludified forests and stretches of open wetlands, peatlands and dark ponds. Whenever I went outside of the car to take pictures, blackflies swarmed around my face in a dark cloud, eager for a morsel of me. I tried to ignore them, took my shots, then fled to the safety of my car.

The farther north I travelled, the more exposed bedrock I saw. I tried to imagine how uplift and depression, mountain building and erosion and glacial action exposed these once deeply buried rocks within the earth’s crust—highly metamorphosed by intense heat and pressure. One scientific paper mentioned a vertical displacement in the CMB shear zone of 5-6 km at temperatures of 450-500 °C. The Gooderham area is particularly known for large zircon crystals, corundum, nepheline, magnetite and biotite.

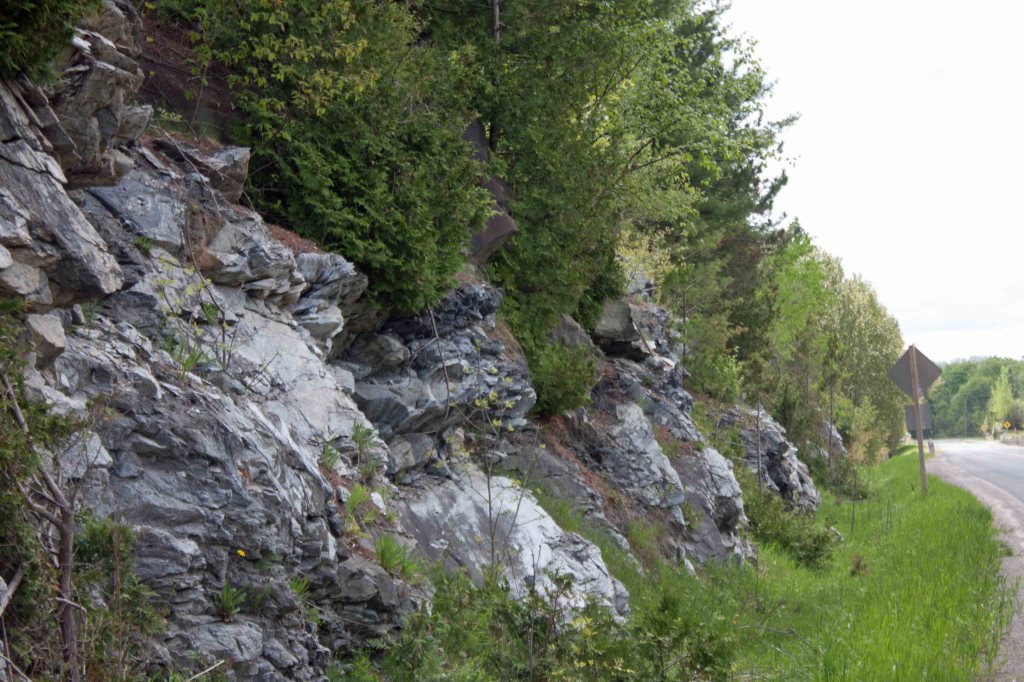

As I approached Gooderham, I saw different rock formations, some pink granite, others black to steely grey; and many streaked and layered with crazy folds. Yet others looked like they were spray painted with white paint or concrete—which I figured was limestone.

Limestone is a rock made of calcite, a mineral made mostly of calcium carbonate; calcite is, next to quartz, the most abundant of Earth’s minerals. Most limestone is grey to white. All limestones are formed when the calcium carbonate crystallizes out of solution or from the skeletons of small shelled sea animals (this area was once an inland sea). Heat and pressure has altered the calcite in the Grenville limestone (altering it to marble, dolomite, and diopside); the calcite crystals lock together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, forming mostly marble, a metamorphic rock. Layers and striations in the marble come from layers of clay or sand in the limestone.

Treasure South of Gooderham: Graphite Spheres

I’d learned that some of these formations also harboured a particularly rare and precious treasure. Just south of Gooderham, about 0.6 km from the cross road, are road cuts with an occurrence of scapolite (mauve-greyish blue-colourless) in a metamorphosed marble deposit as well as brown-green tourmaline, serpentine, mica, pyrite, graphite and sphalerite.

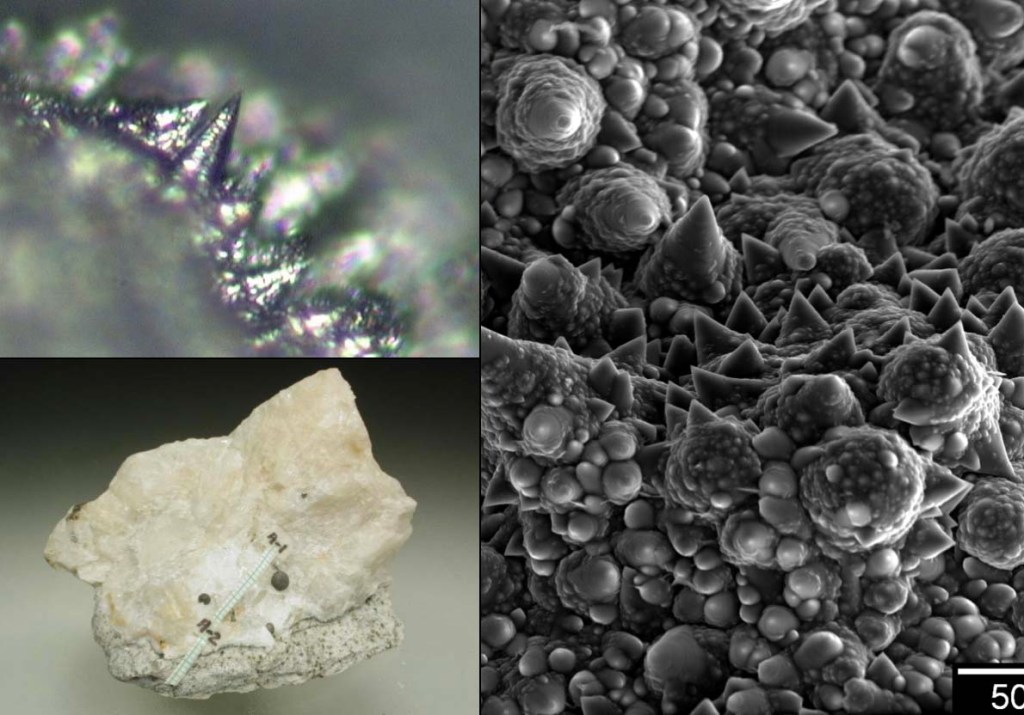

In a stretch from 3 to 5 km south of Gooderham (along the Bancroft shear zone) and in particular an eastern road cut 3.6 km south of Gooderham, scientists from Michigan Technological University identified spherical, spheroidal and ‘triskelial’ aggregates of graphite (0.1 to 10 mm in diameter) embedded in calcite veins (boudins) up to 30 cm across. Their microscopic study showed that the graphite cones range in size from sub-micrometer to 40 microns tall, have a variety of apex angles, and can be sharp or rounded.

Their microscopic study showed that the graphite cones range in size from sub-micrometer to 40 microns tall, have a variety of apex angles, and can be sharp or rounded.

Boudins are cylinderlike structures that make up a layer of deformed rock and are basically fragments of original layers that have been stretched and segmented. The term comes from the French word for ‘sausage’. The boudins in this area were mostly calcite marble, varying from creamy white to orange and pink. Jaszczak and Robinson described the boudins they observed as “coarsely crystalline calcite marble lenses in a highly mylonitized area in the south-western end of the Bancroft shear zone (Carlson et al., 1990) in the Central Metasedimentary belt of the Grenville province.”

Mylonitization describes a rock’s deformation by extreme microbrecciation, without obvious chemical reconstitution of granulated minerals. The resulting mylonite is a foliated rock with strong lineation; its original texture has been modified by plastic flow due to dynamic recrystallization; this occurred below a brittle fault in the crust, at least four km in depth, in the ductile shear zone (see Figure 2).

What made these marble mylonites even more interesting than they already were was the discovery of graphite spheres embedded in them. In 1999, Jaszczak and colleagues described a particular boudin find and showed a photo of a scientist sitting beside a boudin that contained: “calcite bearing spherical graphite with adjoining gneissic, schistose, and marble layers. This is the same boudin shown to the right of the scientist in the road cut.”

Inspired, I sought out the same site. I knew it was 3.6 km south of Gooderham in an eastside exposed formation of a road cut. The road cut was large, stretching some forty feet along the road, and I couldn’t locate the site from the poor-grade photo, which had been taken 25 years ago. Undeterred and looking for marble mylonites, I proceeded to clamber over boulders and ledges and clawed my way over the forty to fifty foot long road cut of highly sheared layers. I found several calcite lenses: one was creamy-coloured, whitish and lumpy or brecciated (#1 boudin); another was pink to orange and cleaved (#2 boudin). As I continued, black flies persistently buzzed and bit viciously around my head and neck. I tried to ignore them and continued my search.

#1 boudin I determined was coarse crystalline calcite marble: a marble mylonite and feldspar/amphibole skarn with brecciation from shearing. The boudin was hiding under a ledge of a large overhanging boulder and contained what looked very much like an embedded graphite sphere about 2 mm in diameter.

When I returned home and compared the photos I took with those of the MTU scientists they matched! I’d found what they found! I felt vindicated in my persistence against the black fly onslaught, though my neck was a topography of aggravated bumps from their nasty bites.

Why Graphite is Cool

Jaszczak and colleagues tell us that because of its crystal structure, graphite shows an incredible versatility in forming unusual morphologies, textures and structures from macroscopic to nano scales. They can occur as tabular columnar hexagonal prisms, complex networks of contorted sheets, and even spheres. In Chapter 6 of the 2006 Nanomaterials Handbook, Dimovski and Gogotsi describe weird graphite shapes such as whiskers, cones, scrolls, and polyhedral crystals.

Graphitic carbon structures remain of tremendous interest because of their promise for potential technological applications that derive from their unique mechanical and electrical properties. Some uses of these forms of carbon include:

- Materials engineering: graphitic cones and polyhedral crystals will enable the development of new functional nanomaterials and fillers for nanocomposites.

- Chemistry and biomedicine: in the development of new chemical sensors, cellular probes, and micro-/nanoelectrodes.

- Analytical tools and instrumentation development: cones and polyhedral crystals can act as probes for atomic force and scanning tunneling microscopes.

- Energy, transportation, and electronic devices: as materials for energy storage, field emitters, and components for nanoelectromechanical systems.

References:

Barrett, David. 2021. “Canadian Shield.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Original entry February 7, 2006; edited August 11, 2021.

Carlson, Katherine A., Ben A. van der Pluijm and Simon Hanmer. 1990. “Marble mylonites of the Bancroft shear zone: Evidence for extension in the Canadian Grenville.” Geological Society of America Bulletin 102: 174-181.

Daxberger, Heidi. 2022. “Introduction to the Geology of the Central Metasedimentary Belt.” In: Atlas of the Central Metasedimentary Belt Bedrock Geology in Southern Ontario. Ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub.

Dimovski, Svetlana & Yuri Gogotsi. 2006. “Graphite Whiskers, Cones, and Polyhedral Crystals.” Chapter 6 in Nanomaterials Handbook, Yuri Gogotsi, editor. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, New York.

Easton, R.M. 2012. “Precambrian Geology of Cavendish Township, Central Metasedimentary Belt, Grenville Province.” Ontario Geological Survey Open File Report 6229. 142pp + appendices.

Jaszczak, John A. and George W. Robinson. 1999. “Spherical and triskelal graphite from Gooderham, Ontario, Canada.” Proceedings of the technical session of the 23rd Rochester Mineralogical Symposium, Rochester, New York, April 16, 1999. In: Rocks & Minerals 75 (2000) 172-173.

Jaszczak, John A., George W. Robinson, Svetlana Dimovski, and Yuri Gogotsi. 2003. “Naturally occurring graphite cones.” Carbon 41: 2085-2092.

Moretton, K. 2007. “Delineating the geometry of the Central Metasedimentary Belt Boundary Zone of the Grenville Province: Nd isotope evidence of a failed back-arc rift zone between Minden and Bancroft.” PDF. Semantic Scholar.

Turner, Bob, Marianne Quat, Ruth Debicki, and Phil Thurston. 2015. “Killarney: Famous Canadian Shield White Mountains and Pink Shores. GeoTours Northern Ontario series.” Natural Resources Canada and Ontario Geological Survey.

van der Pluijm, B.A. and K.A. Carlson. 1989. “Extension in the Central Metasedimentary belt of the Ontario Grenville: Timing and tectonic significance. Geology 17: 161-164.

van der Pluijm. 1991. “Marble mylonites in the Bancroft shear zone, Ontario, Canada: microstructures and deformation mechanisms.” Journal of Structural Geology 13 (10): 1125-1135.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto.

Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

4 thoughts on “The Road to Gooderham and Its Hidden Treasures”