It’s late autumn in the Kawarthas and my boots shuffle through piles of dry leaves on the trail of the swamp forest. Mostly poplar leaves. They curl yellow and brown like dry paper that crumples satisfyingly under my boot or lie limp and silent like soft paper maché as I step lightly on their yellow and grey faces.

.

Above me, in the closed canopy of cedars and poplars, there are still many bright yellow leaves quivering in the breeze and glowing like melted butter in an azure sky. The leaves of Trembling Aspen (Populus tremuloides) quake and tremble with the slightest breeze because they are very light and are attached with a flat petiole, perpendicular to the leaf blade, which helps catch the breeze like wings. My gaze is caught by their brilliant show. Thousands of lemon yellow disks shiver in a warm wind with the sound of change. The aspen is famous for this show of bright lemon and gold.

But not all aspen leaves turn bright yellow in the fall; some rogue trees put out flaming orange and red, even purple-red, leaves. It’s downright scandalous!

.

During my autumn walks through various Kawartha forests, I’ve come to recognize individual aspen trees that like to go orange, red and even purple-red every autumn—renegades amid their conventional yellow neighbours. They do it every autumn. And it’s mostly the Largetooth Aspen (Populus grandidentata) tree that flames orange-red instead of bright yellow, despite being surrounded by the yellows of the same species.

.

Some leaves, I noticed, had only gone halfway red as if they were having problems making up their minds. Others seemed to ‘grow’ into red, displaying remnant yellow veins in a mostly red leaf. I came to realize that these rogue trees demonstrate various iterations of eccentric colour from leaves with a yellow base and branches of red or orange to a section of leaf gone rogue red; to the entire leaf flaming brilliant orange-red.

What is at the root of this revolution?

My first thought was…

Tree Clones!

Largetooth Aspen is often mixed with the more common and wider distributed Trembling Aspen, given that both are early successional trees that aggressively colonize disturbed areas and poor soils impacted by wildfires, avalanches, logging or other major events. They do this through asexual expansion by cloning themselves; they send shoots up through their wide network of roots to create genetically identical individuals (ramets). Michael Grant in Nature.com argued that the many benefits of asexual expansion—spreading via roots which then send up shoots to produce whole stands of “trees”—provides yet another key element in explaining the species’ ability to occupy huge geographic ranges: “One part of a clone might be near an important water source and thus “share” that water with other parts of the clone while those in a drier area may have greater access to a vital soil nutrient (e.g., phosphorus) that can also be distributed around the clone.”

.

.

Aspen clone colonies can consist of a few to hundreds of genetically identical trees, all the same sex (because, unlike most tree species that are monoecious with both sexes on a tree, aspens are dioecious, occurring as only a male or female tree). Some people consider the Trembling Aspen to be the largest living organism in the world, with some colonies living to be thousands of years old. A colony in Utah, known as Pando is believed to be around 80,000 years old. In Natural Lands Tim Burris shares that clone colonies take on a ‘dome’ shape, with the mother (original) tree often being the tallest: “in college I worked for my favorite professor collecting and analyzing samples for her research on Quaking Aspens. During the research, I could recognize an Aspen clone at long distances. You learn to recognize the ‘dome’ shape of a clone. Like most clones in open areas, the parent tree is the tallest and in the center, and each year new shoots pop out around the edge. This gives the clone a dome or umbrella shape.”

Do these rogue trees simply belong to different clone ‘mothers’?

.

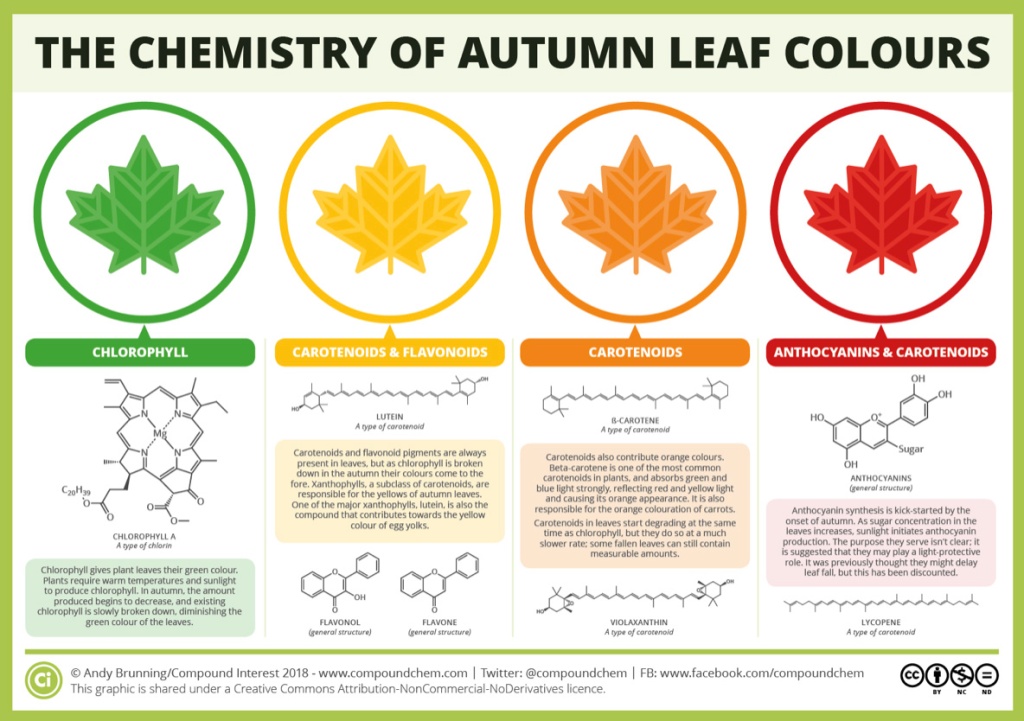

Then I read Michael Grant’s case study in Nature.com, which argued that the variations in leaf colour—from gold, yellow, rose and red—do not mark clonal boundaries. Grant went on to suggest that the chemical processes that produce colours “tend to be very sensitive to local micro-climate conditions such as aspect (whether north or south facing), soil moisture,” and other micro-variables. Grant observed that “a single clone may exhibit multiple colours simultaneously.” All the pigments (e.g. yellow xanthophylls, orange carotenoids, and red-purple anthocyanins) that give rise to these glorious colours can be found in an aspen leaf from spring through fall. As temperatures drop, the tree begins to break down the green chlorophyll molecules (responsible for photosynthesis) that dominate the spring and summer colour, allowing the remaining pigments to become more visible. According to Grant, micro-environmental conditions likely affect chemical processes in individual trees and even individual leaves (e.g. upper and lower in the canopy) regarding loss of chlorophyll and revelation of various pigments.

Aaron Sidder in Medium tells us that aspen trees in the same clone will change colour at the same time, and this may differ in timing with their neighbouring clones. Sidder acknowledges that the rate of leaf colour change is also governed by environmental factors such as temperature, sunlight, and soil moisture and varies by species.

.

Chlorophyll breaks down more quickly with ample sun and low temperatures, especially after the formation of the abscission layer. The combination of cool temperatures, particularly at night, and sunlight also stimulate more anthocyanins, the red and purple pigment in the leaf. Of course, if the cool nights are too cold they will destroy the leaf and end the production of anthocyanins. Frost and drought can cause leaves to prematurely brown and fall.

In a previous post “The Magic of Autumn” I describe the role of pigments in keeping leaves green and the conditions that change leaves into bright beacons of autumn.

.

Why Are Most Leaves Green in Summer?

Chlorophyll a is the pigment that makes most leaves green in spring and summer. It’s a chelate with a central metal ion bonded to a large organic molecule. Its central magnesium atom is surrounded by a nitrogen-containing aromatic porphyrin ring with long carbon-hydrogen phytol chain that allows chlorophyll to absorb red and blue light and reflect the green we see, masking the other secondary pigments.

.

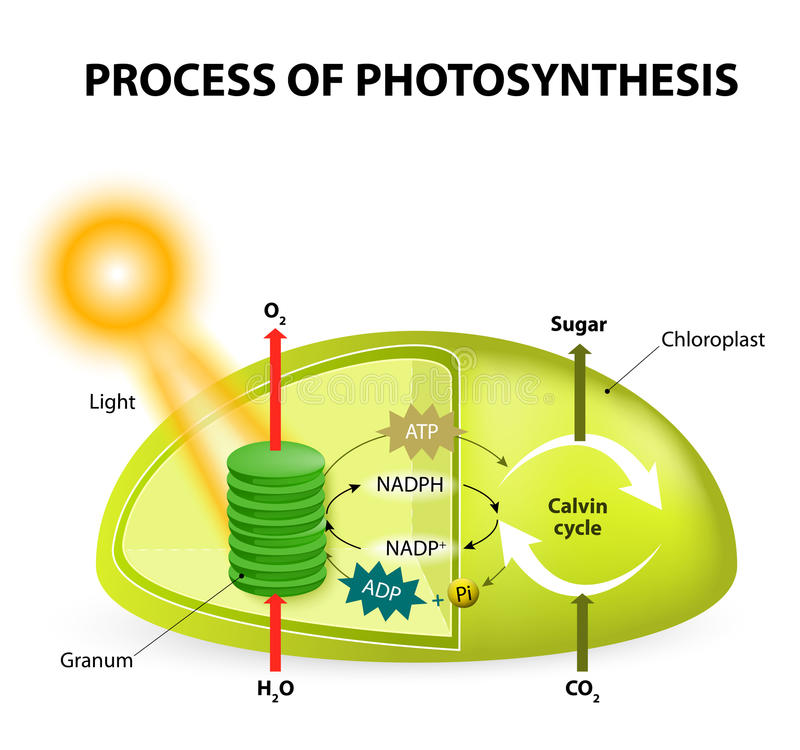

Absorption of sunlight by chlorophyll in the chloroplast of the leaf excites electrons that kick off the photosynthetic reaction to produce sugar. Photosynthesis is basically an energy factory that uses sunlight to make carbohydrates such as starch and sugar from carbon dioxide and water and gives off oxygen as a by-product. Sugars, in turn, are used by the plant to live and grow.

.

What Happens in the Fall?

Signaled by shorter day lengths and lower night temperatures in late summer and early fall, the tree prepares for dormancy by re-absorption of nitrogen and phosphorus from the leaves into the tree’s woody tissue (where it acts as an antifreeze for the tree and an infusion of nutrients for early spring growth); hormones and enzymes chemically trigger the leaf sealing and shedding process, which includes the production of abscisic acid that triggers the creation of an abscission layer. Special cells develop where the stem of the leaf (petiole) attaches to the tree branch and this layer gradually severs the tissues that support the leaf, stopping the flow of water into the leaf (drying it) and with it further production of chlorophyll, leading to abscission. The tree seals the cut, so that when the leaf is finally blown off by the wind or falls from its own weight, it leaves behind a leaf scar.

.

As a tree prepares to lose its leaves, chlorophyll breaks down in the sun and the leaf dries. The breakdown in chlorophyll now reveals previously masked pigments, which may include yellow flavonoids and xanthophylls, and yellow to orange carotenoids (e.g. beta-carotene, lutein, and lycopene). These pigments now reveal themselves through subtraction (of masking chlorophyll): the golden and lemon yellows of American elm, trembling aspen, paper birch, and black willow.

.

The autumn reds are produced by addition. The addition of sugars and leaf waste stuck in the leaf due to plugged petioles help produce anthocyanins, (also flavonoids), which are only produced in the fall: the red of sumac, blueberry, red maple, and Virginia creeper; the purple-blue of white ash, and the purples of viburnum and dogwood. If the leaf sap containing anthocyanin is acidic, the leaves turn red; if the sap is alkaline, they turn blue or purple. The pH of the sap relies on environmental conditions including sun and temperature. Anthocyanin is a sun pigment, so cloud cover plays an important role. If little anthocyanin is produced a leaf may go from green to yellow; if more anthocyanin is made, then red, orange and purple will express.

The browns and coppers in autumn leaves result from tannins, a chemical that exists in many leaves, especially oaks. The persistent brown-copper coloured marcescent leaves of oak and beech trees result because of lack of the abscission layer enzyme. Because marsescence occurs mostly in juvenile trees, this slowing process of leaf loss may be beneficial for growth and nutrient sequestration, given that smaller trees often receive less sunlight.

.

Weather & Micro-Environment Affects Aspen Pigment Expression

Given that aspens also contain the same three sets of pigments as the sugar maple, the explanation offered by Ted Levin in NorthernWoodlands for sugar maple fall variation is equally relevant for the Largetooth Aspen:

“Sugar maple leaves contain all three pigments – xanthophyll, carotene, and anthocyanin – and as go the sugar maples, so goes fall color. Sugar maple leaves turn yellow in the shade, red in the sun, and, depending on the proportion of sun and shade, and on genetics, they change hourly from yellow to red to orange. The red moves down from the top of the tree and in from the sides. The higher the content of sugar trapped in the leaves, the more brilliant the color. Each leaf has its own pattern. Yellow spreads from the leaf margins inward. Green retreats to the veins. Soon, the veins, too, turn yellow. Finally, the whole tree is orange, dusted with red, inlaid with yellow.”

Ted Levin, Northern Woodlands

.

Genetic Variation Still Plays a Part

Then I read an article by Ned Rozell in a post for the Geophysical Institute of the University of Alaska who quoted the work by Kuo-Gin Chang, Gilbert Fechner and Herbert Schroeder (then at Colorado State University). They determined that “an apparent, unidentified carotenoid pigment was synthesized in all colored leaves [of quaking aspen] during autumn, but not in yellow-leaved aspens.” They also identified two anthocyanin pigments in red-leaved and orange-leaved aspens that were not found in yellow-leaved aspens. The red that only occurs in some aspen individual trees “is probably a genetic trait—a red aspen is sort of like a person with red hair.” The researchers also observed that the yellow trees remained yellow from year to year and the trees with red leaves at the start of their five-year study were red only for the first year and turned yellow each following year. This differed from my own observation of persistent red leaves (over at least four years) of individual trees I’d singled out during my forest walks.

.

My Conclusion…

SO! I think both genetic and environmental factors influence a tree’s fall colour expression of its leaves. Is it possible for an individual tree, not part of an identical clone cohort, to find its way in that ‘exclusive’ crowd? Likewise, can the variability of environment (moisture, aspect, wind, etc.) determine micro-differences that translate into unique pigment creation and singular expression of an individual tree (ramet) or group of trees belonging to a larger clone? Can a singular expression of a ramet (individual clone tree) arise from micro-environmentally induced epigenetics?

It’s still a wonderful mystery!

.

Ted Levin adds rather pithily that the colour pageant of the aspen [out west] “is not the same as ours [in New England, renowned for its brilliant fall maple colours]. The genius of one sugar maple is worth an entire hillside of aspen. It’s like comparing Mozart to Manilow. Aspen is yellow, often yellow only, whereas sugar maple is moody, unpredictable, its colors an ephemeral reflection of the weather. They cannot be spoken. They’re too varied, too rich, too unstable.”

While I admire Mr Levin’s artistic spirit for the sugar maple and I too adore the genius of this iconic tree, I appreciate the occasional sassiness of aspen: how a single tree within a stand of conservative yellow can subvert its own autumn tradition and unabashedly express its unique song. The aspen is not as flamboyantly showy as the diva sugar maple but its rather coy splash of red, orange and even purple is all the more significant and equally beautiful as it is mysterious.

.

References:

Barnes, B. V. 1966. “The clonal growth habit of American aspens.” Ecology 47: 439-447

Farrar, John Laird. 1995. “Trees in Canada.” Natural Resources Canada. Ottawa. 502pp.

Field, Taylor S. et al. 2001. “Why Leaves Turn Red in Autumn. The Role of Anthocyanins in Senescing Leaves of Red-Osier Dogwood.” Plant Physiol. 127(2): 566-574.

Frazer, Jennifer. 2015. “Root Fungi Can Turn Pine Trees Into Carnivores—or at Least Accomplices.” Scientific American, May 12, 2015. Online: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/artful-amoeba/root-fungi-can-turn-pine-trees-into- carnivores-8212-or-at-least-accomplices/

Grant, Michael. 2010. “Case Study: The Glorious, Golden, and Gigantic Quaking Aspen. Nature Education Knowledge 3(10):40

Hansen, E. A. & Dickson, R. E. 1979. “Water and mineral nutrient transfer between root systems of juvenile Populus.” Forest Science 25: 247-252

Hardy, Rich. 2020. “The 500-million-year-old reason behind the unique scent of rain” New Atlas.

Lee, David W. et al. 2003. “Pigment dynamics and autumn leaf senescence in a New England deciduous forest, eastern USA. Ecological Research 18: 677-694.

Munteanu, N. 2019. “The Ecology of Story: World as Character.” Pixl Press, Vancouver, BC. 198pp. (Section 2.7 Evolutionary Strategies)

Munteanu, N. 2020. “A Diary in the Age of Water.” Inanna Publications, Toronto. 300pp.

Peltzer, D. A. 2002. “Does clonal integration improve competitive ability? A test using aspen (Populus tremuloides (Salicacae) invasion into a prairie.” American Journal of Botany 89: 494-499

Sider, Aaron. 2017. “The Science Behind Aspen Leaf Color Change.” Medium, September 7, 2017.

Vogel, Steven. 1993. “When leaves save the tree.” Natural History 102: 48-63

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

Thank you for this! I live in Maine and know only yellow aspens and poplars near my home. I just got back from Baxter State Park and was perplexed by aspens I saw there turning red-orange?!? Thought I was looking at a different species, but now I see it was just a flamboyant bigtooth!

LikeLike

Yes, they certainly are! Thanks for sharing, Juliet. Best, Nina

LikeLike