.

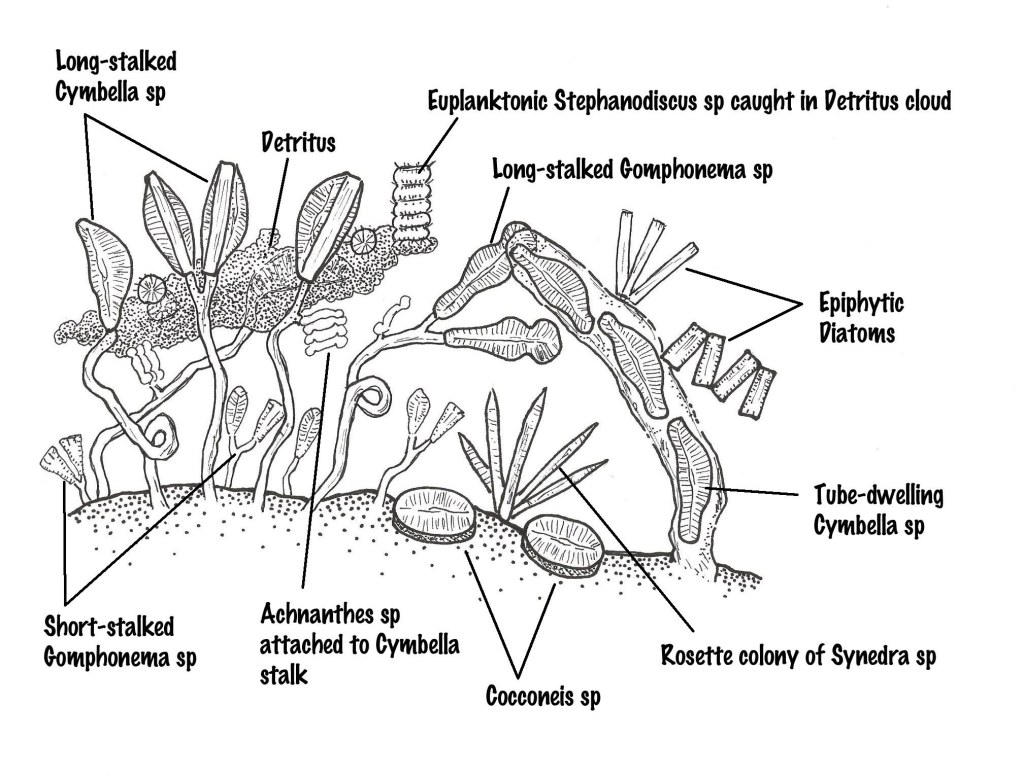

I’ve always been fascinated by the miniature worlds of Nature, the things you don’t often see. I spent years studying microscopic biota inhabiting freshwater streams in Quebec. I did my masters research on the diatom forest, a microscopic forest with overstory and understory layers much like a forest of trees but in a stream. I published a scientific paper, several online articles and saw my scientific drawing published in a Dutch scientific journal.

These days, my forest walks give me an entire miniature world of lichens and mosses to discover. Most recently, I’ve been visiting them on a granite rock outcrop that edges into the marsh of the Catchacoma old-growth hemlock forest.

My sister even gave it a name: Catch Rock.

.

Catch Rock: Its Region & Local Ecosystem

Catch Rock is a granite-gneiss outcrop, oriented generally north-south, that protrudes out like a peninsula of an old-growth hemlock forest into an open sphagnum mineral meadow marsh. The Rock and the forest is located on the Precambrian Canadian Shield of Ontario, the Earth’s greatest area of exposed Archean rock. The Canadian Shield is an area of exposed Precambrian igneous and high-grade metamorphic bedrocks that formed over 3 billion years ago through glaciation, erosion and plate tectonics. The Canadian Shield once had jagged peaks, higher than any of today’s mountains; but over millions of years, wind and rain eroded and wore down these mountains to rolling hills. The giant 3 km thick Laurentide Ice Sheet stripped off what remained of the overlying rock and deposited sediment south.

The GeoOntario Map shows that the underlying geology in this area consists of granite-gneissic rocks with outcrops of Precambrian late tectonic to post-tectonic intrusive rocks of granite, syenite, pegmatitic, and some magnetite. These are generally pink to brick-red coloured with some green and white varieties present. Clearly, Catch Rock is one of these granite outcrops.

The rocky peninsula extends northward into the marsh for about 40 metres, much of which is covered in shallow humic soil and duff with several trees—pine, oak, birch and even beech—established. The northern-most tip of the rock outcrop is mostly bare exposed rock with hollows filled with debris, moss and lichen.

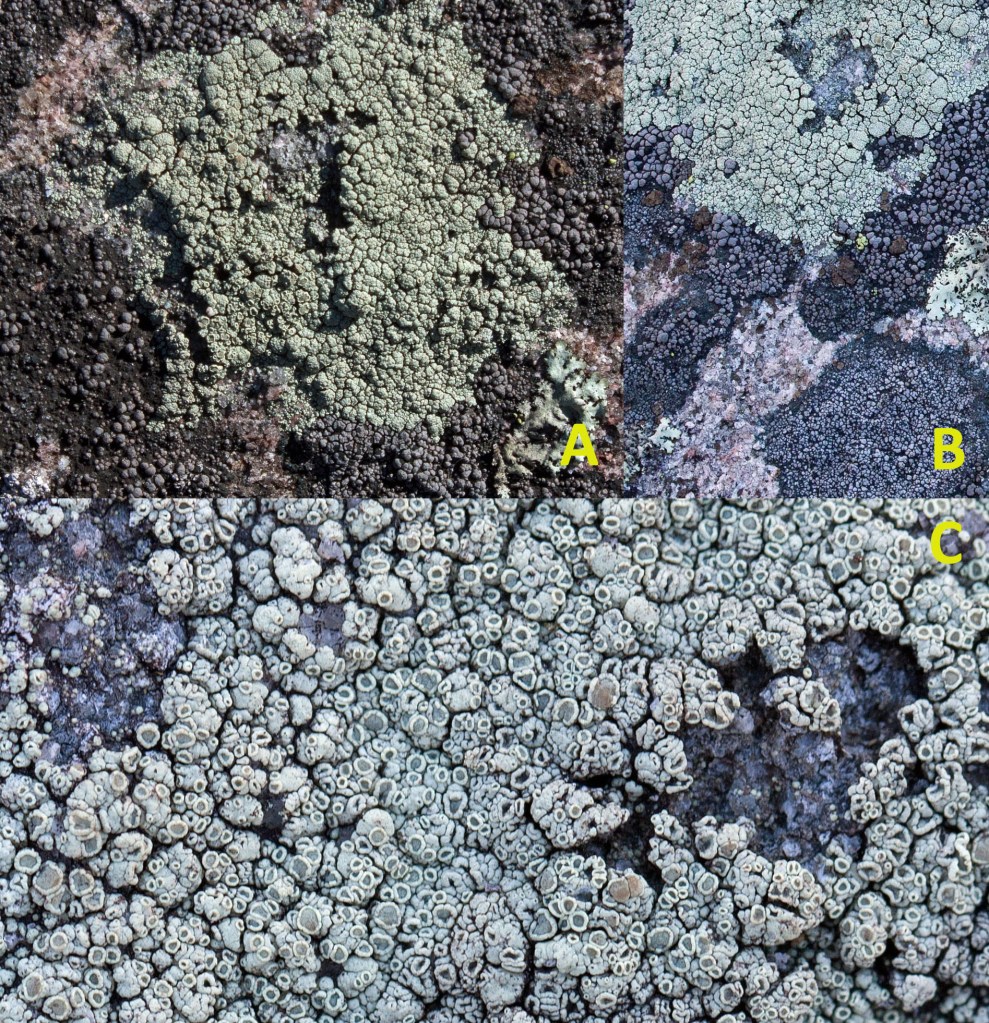

When I first walked to the northern tip of Catch Rock to admire the marsh that it faced, I was struck by the rock itself and how colours, patterns and textures of lichen and moss adorned this already colourful rock. The pinks and greens and clear crystals of granite were variously carpeted with scatter ‘rugs’ of lichen and moss: tiny gray-olive ‘pebbles’ formed thin textured cushions; specks of bright yellow looked like splashed paint on the rock; bright green-yellow ‘bubbles’ surrounded by black ‘eyeliner’ spread out like amoebas; patches of miniature gray-green ‘leaves’ with cinnamon discs at their centres circled ever outward; tiny branching gray to pale green ‘trees’, dotted with chocolate brown to purple or cherry red blobs, formed frothy cushions.

Lichens that inhabit rock substrates are called saxicolous and are divided into three groups based on their structure and mode of attachment: crustose (flattened and crusty or powdery), foliose (raised, leaf-like lobes), and fruticose (branched growths with finger, cup, or thread-like projections). Crustose lichen tend to be the most abundant lichen on rock, often growing circularly outward; they can be further divided into epilithic (living on the surface of the rock) and endolithic (living inside the rock).

For more about lichens in general, see my article The Magic of Lichen. For a clear description of the three lichen types, structure and fruiting bodies, What’s Growing in Colorado includes clear illustrations.

- For Crustose Lichen three main structures include: 1) Apothecia (fruiting bodies), typically cup or wart-shaped and often a different colour; 2) Thallus, which may be warty, wavy, or grainy, but always fused to the rock; Margin, the growing fungal edge of the lichen, a different colour and often black and flatter and less textured than the thallus.

- For Foliose Lichen, five main structures include: 1) Apothecia, usually cup-shaped; 2) Thallus, with curling ‘leaves’ spreading out from the centre as lobes; 3) Rhizines, root-like structures that anchor the lichen; 4) Isidia and Soredia, sporulating structures that look crusty or dusty; 5) Pycnidia and Parithecia, sunken sporulating structures resembling sunken black pores studding the thallus surface. Foliose lichens also spread outward circularly, often leaving the centre to disintegrate.

- For Fruticose Lichen, structures vary greatly. These lichen maintain a 3-dimensional structure by wrapping the medulla in the cortex, creating bizarre cup shapes, horns, filaments and so on. Fruticose lichen are often distinguished by their greatly varying thallus and fruiting body.

Catch Rock communities of lichen and moss jostled for prime real estate and showed various stages of colonization, growth, and association. The sun-exposed northern end of Catch Rock was covered mostly by various flat crustose lichen with some islands of established branching lichen colonies. On east-facing hollows and inclines, where moisture lingered like vagrants in an alley, crowds of branching foliose and fruticose lichen crowded in a dense carpet of water-retaining mosses like Bristly Haircap (Polytrichum piliferum), Bog Haircap (Polytrichum strictum), Dicranum sp. and Sphagnum spp. to create miniature scrub forests.

.

The most abundant moss associated with the lichen on Catch Rock was the Bristly Haircap, Polytrichum piliferum, a bluish-green to gray evergreen perennial moss that forms loose tufts 2-3 cm high with stems becoming wine-reddish with age. The smallest of the haircap mosses, Polytrichum pilifrum commonly grows on open dry and acidic sites low in nutrients, such as shallow soil over outcrops, rocks and boulders. It is extremely tolerant of long periods of dryness and high temperatures in its open sunny habitat. The Bristly Haircap’s distinguishing feature, and the one that gives it its common name, is the long, white hyaline awn at the tips of its leaves, which also give this moss its grey colour. P. piliferum is known to associate with species of Cladonia. P. piliferum is dioecious, having male and female plants; males use a splash-cup to disperse sperm from their antheridia and females have archegonia to which the sperm swim to. Their acrocarp capsules that bear the sporophyte sit on bright red shoots (see previous image labelled C.).

.

At the south end of the outcrop, merging into the forest and beneath the shade of a pine tree and several nearby hemlocks and oaks, the litter-filled shallow-soiled areas of Catch Rock harboured club mosses. I recognized Ground Cedar (Diphasisastrum complanatum) peaking through pine needles and oak leaves. Below, on the marsh-edge in a crowd of Bog Haircap Moss, were several Ground Pines (Dendrolycopodium obscurum [previously called Lycopodium obscurum); these four-inch high conifer-looking plants were reaching skyward just as their giant 100-foot Carboniferous ancestors.

Club moss is an ancient group of seedless vascular plants in the phylum Lycophyta; these were once giant trees (100 feet high) before the dinosaurs roamed the earth. Lycopodium is one of the oldest plants on earth; never evolving into flowering plants and still reproducing through spore release in the form of a dusty powder. Nina Veteto at Blueridge Botanic shares that the high fat content of the powder is highly flammable and was used to create gunpowder, fireworks, and flash powder for old camera flashes. This shaded area of moist shallow humic soils also harboured several species of Cladonia lichens, notably Cladonia squamosa, known as Dragon Horn.

The west-facing incline of Catch Rock was steep, with mostly crustose lichen, and ended abruptly in a flat of brilliant red Sphagnum magellanicum. Bog Haircap Moss (Polytrichum strictum) and Bog Cranberry spread out westward into the marsh-proper.

.

Lichen: A Natural Story

Scientists have estimated that around 8% of the terrestrial surface of the earth is covered by lichen-dominated vegetation. Lichen are the first colonizers of bare rock and new soils. Mats of Cladonia and Stereocaulon may cover from 50-90% of northern environments. Lichens date back to the Early Devonian Period, some 400 million years ago. Several hundred-year-old lichen are commonly reported. Ages of up to 4500 years were reported for the crustose Rhizocarpon geographicum in Greenland and Swedish Lapland. As the earliest colonizers of terrestrial habitats on the earth, lichens are among the most successful forms of symbiosis. And part of their success lies in their versatility and shapeshifting qualities (more on this later) that includes a vagrant lifestyle for some (aka tumbleweeds) and an incredible diversity in shape, texture and colour—even within the same lichen organism—called a photomorph.

Unless highly pigmented, the lichen cortex (made of fungal cells) looks gray or greenish-gray when dry. When wet, the cortex becomes transparent, allowing the algal layer to show through with bright green or olive colours, which enhances photosynthesis under better conditions of moisture.

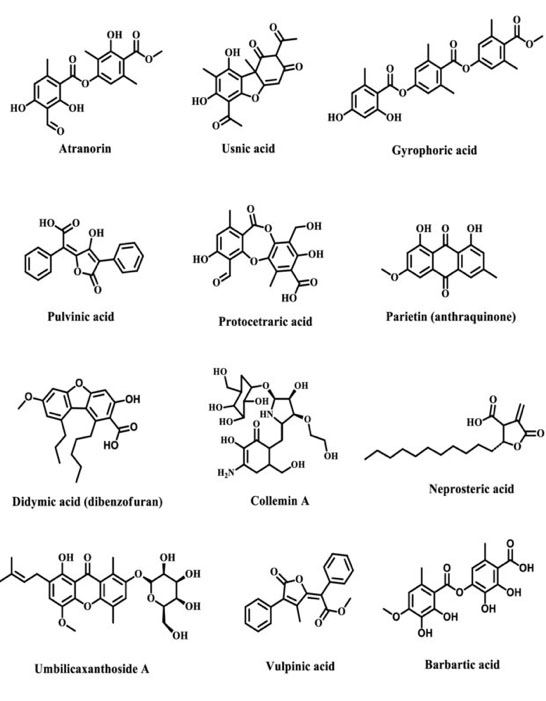

The secondary metabolite pigments produced by the fungus serve a myriad of functions. Aside from making lichens wonderfully colourful, they help deter foraging by herbivores such as moluscs; they are allelopathic, helping against competitors; they help weather rock; and they act as sunscreen. You could say that the fungal layer serves as a ‘greenhouse’ for the photosynthesizing algal layer.

Melanin, which is effective against UV radiation, gives lichen a brown colour. The most widespread pigment in lichens is usnic acid, which gives Usnea and Xanthoparmelia their characteristic pale yellowish-green or “usnic yellow” colour. Xanthones add the yellow colour to Buellia halonia. Pulvinic acid colours species of Vulpicida, Letharia and Pleopsidium a brilliant yellow. And bright yellow, orange or red anthraquinones brighten Caloplaca, Xanthoria and the bright red fruiting bodies of British soldiers (Cladonia cristatella). Factors that affect colour expression in any individual lichen include age, exposure to sunlight, temperature and genetics, among others. Just as with aquatic algae, the photobiont of a lichen can be damaged by too much light, particularly UV light, so it uses pigments as ‘sunscreen.’ Lichens with the most intense colours are those most exposed to sunlight and lack of moisture. If present, cyanobacteria with its associated pigments will darken the lichen as well as fix nitrogen from the air. Usnic acid is most effective against short wavelength UV light; pulvinic acid absorbs longer wavelength UV light as well as providing a toxin against potential herbivore grazing. Brodo and colleagues suggest that thallus colour may also help regulate temperature within the lichen; Arctic and alpine lichens tend to be darker than their temperate cousins and many of these likely contain cyanobacteria as one of their photobionts.

.

.

Lichen’s Natural Succession: Growing Faster than Light By Just Being There…

As with mosses and fungi, lichens are pioneer organisms, colonizing substrates such as bare rock and the surface of glaciers. Formed through symbiosis between fungi and algae (and sometimes yeast), lichens are often the first to colonize newly created environments or recently disturbed environments during the process of natural succession. Succession on rock begins with crustose lichen (e.g. Acarospora, Porpidia, Rhizocarpon, and Lecidea). Rock shields (Xanthoparmelia) are common foliose lichens that follow, leading to more foliose and climax fruticose lichen (e.g. Phaeophyscia, Parmelia, Cladonia) along with companion mosses.

Once established, lichens take their time when it comes to growth. According to Mason E. Hale, growth of crustose and foliose species usually occurs at the margins, spreading out, and leaving the centre to disintegrate. The freshly exposed rock surface at the centre is colonized by other lichen, usually from nearby. Fruticose species grow mainly in height and length. Hawksworth and Rose noted that British crustose and foliose lichen spread radially about 0.5 to 5.0 mm a year. Fruticose species grew more quickly, achieving 1-2 cm in height or length in a year.

Rock provides a stable growth surface for long-term attachment of saxicolous lichen; their general texture and mineral content also affect the success and rate of lichen growth and spread. Part of this is obviously related to the lichen’s absorption and uptake of some elements. I’m told that on granite, lichen hyphae can grow several millimeters into the rock; on other rocks like limestone, their hyphae can reach up to 16 mm deep.

.

How Lichens Change the World

Lichens trap and absorb water and minerals from raindrops, water vapour, and dust. As they grow, they weather and break down the rock, physically and chemically, in a process called bioweathering.

Chen and colleagues reported that lichen colonization induces weathering of rocks through both physical and chemical processes. Physical effects include mechanical disruption of rocks caused by hyphal penetration, expansion and contraction of lichen thallus, swelling action of the organic and inorganic salts originating from lichen activity. Lichens weather rocks chemically by excreting various organic acids, particularly oxalic acid, which can effectively dissolve minerals and chelate metallic cations. Weathering of granite by lichens appears to affect the micaceous minerals such as biotite the most. Dissolution of feldspar grains were also observed.

In the 1920s, E. Jennie Fry, when investigating the mechanical disruption of rock caused by expansion and contraction of the lichen thallus, concluded that the mechanical force exerted through wetting and drying was significant. Enough to break rock. Crystallization (and swelling) of secondary salts (various oxalates) excreted by the lichen may also cause mechanical disaggregation and separation of rocks and minerals.

Image in Jung et al., 2020

Like voracious amoebas, lichens even incorporate mineral fragments into their thalli. Scientists found that the lichen Parmelia conspersa contained detached and embedded particles of its granitic rock substrate in the hyphae of its thallus. Calopaca variabilis and Lecanora albescens gobbled up quartz crystal particles. Prieto Lamas and colleagues noted that the thalli of five lichen species colonizing granite had loosened rock-forming mineral grains such as quartz, feldspar, and mica and engulfed them in their thalli.

Chemical weathering by lichens happens in three ways: 1) solubilizing minerals by generating respiratory CO2 to create carbonic acid and lower pH; 2) secretion of oxalic acid by lichen mycobionts that form cation-complexes toward increased hydrolysis; and 3) production of biochemical compounds such as chelating depsides and depsodones. Scientists showed that biotite, granite and basalt formed organic complexes that indicated decomposition of silicate minerals. Alkaline metabolic products and enzymes produced by lichens may also solubilize their mineral substrates.

Lichen colonization results in significant accumulation of organic matter, detaching rock particles and trapping dust and debris to help develop primitive soils. The organic matter and cell excretions encourage bacteria and synergize the weathering process. Nitrogen-fixing further enhance the process by producing humic and fulvic acids. Ultimately, lichens create a favourable microenvironment by increasing bioavailability of mineral elements, water and nutrients to successive life-forms that will eventually replace them. The rate of this transformation, of course, varies according to the type of the rock and the lichen’s own abilities.

.

The Stratified Lichen Forest of Catch Rock

During my tip-toeing on the granite from lichen colony to colony, I observed both horizontal and vertical stratification. Just as a forest ecosystem demonstrates a horizontal distribution as well as a vertical understory and overstory canopy, the lichens and associated mosses demonstrate stratification—from the pioneer crustose spread of shield lichen on bare rock to the heaven-reaching branches of reindeer lichen amid club moss in a detritus-filled hollow.

Studies have demonstrated that within these tiny communities, micro-vertical stratification exists: apical parts of thalli exposed to more strong light, low moisture and higher variability of temperature compared with basal parts of the community. Think of maple trees in the fall: the more exposed tops of the trees show their leaf colour and drop their leaves sooner than the lower more shaded parts of the tree. Noh and colleagues demonstrated that part of the vertical response to the environment of a particular lichen was caused by the vertical distribution of the algal species inside the lichen thallus. The bacterial composition of any part of the foliose lichen Xanthoparmelia also depended on its horizontal position connected to moisture availability and sunlight exposure. Cladonia arbuscular showed differing bacterial communities in its younger upper layer compared to its older basal layer. Apical parts of many thalli exposed to direct sunlight and dry air, produce secondary metabolites like melanin to protect themselves from oxidative stress.

In a moment of sudden clarity, I reflected on Nature’s fractal existence: how the stratified nature of an old-growth hemlock forest is reflected by a stratified lichen forest, and that ‘forest’, in turn, by a microscopic diatom forest.

.

More on Lichen Adaptations

Horizontal patchiness of a given lichen over the surface of Catch Rock is no doubt, related to its patchy mineral content and to the already established moss or other lichen. Noh and colleagues reported that colonies of Cladonia squamosa, capable of saprotrophic nutrition, grew differently near mosses or soil.

To explain various adaptive strategies, Cladoniarium proposed six growth forms of Cladonia based on its composite union of primary thallus (basal squamules) and secondary thallus (podetia and apothecia). The six growth forms ranged from simple foliose of squamules, to fruticose with simple podetia, and finally to fruticose with branched podetia.

.

Cladoniarium argued that because the thallus is composite, pycnidia could occur on either primary squamules or on podetia, depending on the species (i.e., position of pycnidia on the thallus). A lichen producing pycnidia on primary squamules can do it faster than a lichen producing them on podetia, they argue, since squamules develop first. The former strategy would be more effective when colonizing pioneer habitats.

Image by Cladoniarium

Cladoniarium went on to suggest that secondary metabolites produced by Cladonia (including atranorin, zeorin, and fumarprotocetraric, homosekikaic, rangiformic and usnic acids) are significant for environmental adaptations. Farkas and colleagues showed that usnic acid enhanced ‘canopy’ cover while atranorin decreased the thickness of Cladonia canopy cover. They argued that usnic acid was used in exposed sites to reduce potentially destructive light intensity while atranorin helped exploit low light intensities. Using the example of three widespread and dominant but also very different Cladonias in size, morphology and reproductive strategy (Cladonia cariosa, Cladonia rei, and Cladonia rangiformis), Cladoniarium suggested that in fact their shared secondary metabolites were the key to their shared success.

More than 1000 secondary substances have been identified as unique to lichens (mostly made by the fungal part of the lichen) and serving a diversity of purposes from sunscreen, to anti-herbivore grazing, to making unusable energy usable.

Who Lives in the Lichen Forest of Catch Rock

Granite has its own unique composition, texture, mineral content and pH, and even water-holding capability. It is a highly siliceous rock with an acidic pH varying from 4 to 6 and is more resistant to acidic solutions such as acid rain than other stones like marble and limestone. Granite’s unique and varied set of minerals and crystals include silica, which some lichen prefer. Genera known to frequent granite rock include: Aspicilia*, Arctoparmelia, Candelariella*, Lecanora*, Lecidea*, Lepraria*, Parmelia, Porpidia, Pseudephebe, Stereocaulon*, Rhizocarpon*, Rhizoplaca, Umbilicaria*, and Xanthoparmelia*—several of which (asterisked) I found on Catch Rock.

Examples of lichen species I found on Catch Rock follow. The list is hardly exhaustive, but hopefully represents the diverse ecosystem provided by this granite outcrop.

.

FRUTICOSE LICHEN

.

Mealy Pixie Cup (Cladonia chlorophaea)

Mealy Pixie Cup (Cladonia chlorophaea): I found this cosmopolitan lichen all over Catch Rock, from shady/humus soils to bare rock together with British Soldiers (below) and other lichen. It can easily be distinguished by its pale-green goblet-shaped podetia, covered in granular soredia, rising from a messy squamulose thallus. Brown pycnidia are obvious on the cup margins.

.

British Soldiers (Cladonia cristatella)

British Soldiers (Cladonia cristatella): this lichen branches at the tips and lacks the cups of the similar Red Fruited Pixie Cup (Cladonia pleurota). I found this lichen in colonies throughout the granitic outcrop, but mostly in hollows of loose soil, humus and detritus-cover. Scientists had identified another branching pixie cup with bright red apothecia, Madame’s Pixie-Cup Lichen (Cladonia coccifera) in the area (though not specifically the rock outcrop). I was unable to distinguish that species from the similar British Soldiers. Madame’s Pixie-Cup Lichen is most often found in open woods in Canada and the upper Great Lakes on acidic peaty and sandy soils.

.

Pebbled Pixie Cup (Cladonia pyxidata)

Pebbled Pixie Cup (Cladonia pyxidata): The stalks (podetia) of these squamulose lichens form goblet-shaped splash cups with fruiting bodies, reddish-brown tiny ‘blobs’ (apothecia) on their rims. The thallus is grayish-green to olive with primary squamules tongue-shaped. The podetia lack granular soredia and the splash cups have noticeable corticate disc-shaped squamules that look like pebbles, sitting inside. According to iNaturalist, the Pebble Pixie Cup is most often found on soil, especially acidic mineral soil and thin soil over rocks, more rarely over wood, in mainly arctic to temperate regions. I found colonies mostly in hollows and the northeast incline of the outcrop, along with British Soldiers.

.

Gray’s Cup Lichen (Cladonia grayi)

Gray’s Cup Lichen (Cladonia grayi) is known to grow on rocks, soils, old woods, heathlands, logs and mosses. I found it inhabiting various parts of the granitic rock outcrop, mostly on its inclined northeast face. The goblet-shaped stalk or podetia of Gray’s Cup Lichen is greenish to pale grey, usually unbranched and verrucose, often squamulose. Its cup, which can be highly variable, is rimmed infrequently by dark brown apothecia.

.

Dragon Horn Lichen (Cladonia Squamosa)

Dragon Horn Lichen (Cladonia Squamosa): I found this pale grayish-green lichen closer to the forest, in the shallow litter-covered mossy soils of Catch Rock, enjoying the shade of hemlocks and oaks. Its highly squamulosed sparingly branched stalks arose from a sea of pale green scales. Its podentia sometimes carry tan to brown fruiting structures at the tips, which I did not see. The Dragon Horn is most often observed in shady moist forests, where I found it.

.

Gray Reindeer Lichen (Cladonia rangiferina)

Gray Reindeer Lichen (Cladonia rangiferina): I found cushions of this lichen scattered throughout the rock outcrop, but mostly concentrated in the hollows and northeast inclines of the rock. This silver-grey lichen has a main stem that branches like a tree with brownish tapered branch tips and very few with a tiny dark globe that is its fruiting body (pycnidium).

.

Thorn Lichen (Cladonia uncialis)

Thorn Lichen (Cladonia uncialis): I found this lichen cozy with the Gray Reindeer Lichen but spread out more in rounded tufts of pale greenish cushions with many-branched stalks. Thorn Lichen formed mixed communities with moss and other lichens on bare rock and hollows of detritus, moss, and shallow soil. The stalks were mottled green-yellow and the branch tips were brown.

.

Rock Foam Lichen (Stereocaulon saxitile)

Rock Foam Lichen (Stereocaulon saxitile): I found small clusters of this snow lichen in some shady hollows but mostly in the upper sun-exposed granite, often associated with moss, Pixie Cups and Peppered Rock Tripe. It looked ‘frothy’ from my standing position and it was only when I crouched down for a closer look that I recognized that its ‘froth’ was a dense covering of ‘bubbles’ on the lichen branches. The grey to white tree-like branches that emerged from a woody base were covered in coarse rounded squamules or granules (phyllocladia) that looked like yogurt-covered candies.

.

Finger-scale Foam Lichen (Stereocaulon dactylophyllum)

Finger-scale Foam Lichen (Stereocaulon dactylophyllum): I found clusters of this saxicolous snow lichen in the upper sun-exposed granite, often associated with moss, Cladonia and Peppered Rock Tripe. It is very similar to S. saxitile but distinguished itself by terminal round to saddle-shaped reddish to blackish-brown apothecia at the ends of branches. large S. dactylophyllum also prefers siliceous rock in full sun.

.

FOLIOSE LICHEN

.

Cumberland Rock Shield (Xanthoparmelia cumberlandia)

Cumberland Rock Shield (Xanthoparmelia cumberlandia): I saw this yellowish-green lobed foliose lichen tightly attached to the granitic outcrop, mostly on the upper flat and exposed parts. The shield lichen formed large radiating patches with cinnamon to dark brown discs crowding the centre. The leading lobes were typically more pale and had a light bluish hue to them. The brown discs (apothecia) varied in size. This lichen is known to grow on exposed to somewhat shaded rock outcrops and boulders.

.

Peppered Rock Tripe (Umbilicaria deusta)

Peppered Rock Tripe (Umbilicaria deusta):I found patches of this strange dark brown lichen with granular isidia-rich lobes throughout much of Catch Rock’s exposed surface. Its texture looked quite different when wet and when dry. This lichen isknown to enjoy siliceous rocks such as granite and gneiss and is often seen on exposed rock outcrops where it can withstand less moisture.

.

CRUSTOSE LICHEN

.

Yellow Map Lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum)

Yellow Map Lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum): I found this interesting crustose yellow-green lichen with black dots mostly on the upper sun-exposed surface of the granite outcrop. It is normally found on silicate rocks and according to Ryne Douglas Rutherford of Northern Michigan University was restricted to the granite bedrock lakeshore of their study of Lake Huron lichen. William Purvis describes this lichen as “minute yellow green islands, which contain the pigment rhizocarpic acid, growing on a black layer lacking algae.” The black layer of fungus spreads out ahead of the photosynthesizing thallus in an allelopathic role to deter competing lichen. When I first saw the lichen it was after a rainfall, which explains the more green colour, provided by the photosynthesizing photobiont. In dry weather the yellow map lichen is indeed quite yellow.

Rhizocarpon geographicum grows on average 0.5 mm/year. Some of the growths I observed were up to five centimeters in diameter, suggesting that these were at least fifty years old. It is common to find R. geographicum 1000 years old. Specimens over 4500 were reported from Swedish Lapland, rivalling the oldest flowering plants.

.

Single-spored Map Lichen (Rhizocarpon disporum)

Single-spored Map Lichen (Rhizocarpon disporum): I found this crustose lichen throughout the granitic rock outcrop, particularly the sun-exposed north end. This olive to brownish gray lichen with black apothecia resembles a congregation of tiny gray-green-brown pebbles with darker, close to black, warts. This lichen grows on sun-exposed siliceous rock, including Pre-Cambrian granite.

.

Cinder Lichen (Aspicilia cinerea)

Cinder Lichen (Aspicilia cinerea): I found this strange and wonderful lichen on the sun-exposed flat of the granitic rock outcrop. Gray to almost white, this areolate lichen, with large black apothecia, is known to inhabit siliceous, schist or igneous rock exposed to sunlight.

.

Rock Disk Lichen (Lecidella stigmatea)

Rock Disk Lichen (Lecidella stigmatea): I found colonies of this lichen spreading throughout the sun-exposed surface of Catch Rock. It has a dirty white to grey areolate thallus and flat to convex black disks (apothecia). This ubiquitous lichen grows on both non-calcareous and calcareous rock. I originally identified a patch of this lichen as Tile Lichen (Lecidea tesselata), because it likes granite, thrives in full sun, and looks similar. However, the black disks of Tile Lichen are sunken in the thallus and not overtopping the areoles, and its thallus appears more tile-like, particularly when dry.

.

Tile Lichen (Lecidea sp.)

Tile Lichen (Lecidea sp.): This crustose chalky white to blue gray lichen with black sunken disks (apothecia) spread out over Catch Rock in full sun to form circular patterns. All of the 136 species of tile lichens grow on rock, growing within the rock matrix (endolithic).

.

Chewing Gum Lichen (Lecanora muralis)

Chewing Gum Lichen or Stonewall Rim Lichen (Lecanora muralis): I found this beautiful rosette-forming lichen, with lecanorine apothecia and tan disks, spreading over the exposed top surface of the granite outcrop in loose rosettes with leafy-like lobes. This cosmopolitan lichen grows on a variety or rock types from granite to limestone. When dry, the thallus formed pale green areolate ‘lobes’; when wet, the thalli looked more green with polyphyllous squamules. As the name suggests, this lichen likes granite. Because the squamulose thallus looked foliose to me, I originally identified this lichen as Orange Rock Posy (Rhizoplaca chrysoleuca)—also a granite-loving lichen—but its apothecia were not sufficiently orange, abundant and large.

.

Granite-speck Rim Lichen (Lecanora polytropa)

Granite-speck Rim Lichen (Lecanora polytropa), which is a granite-loving lichen is very similar to its cousin Chewing Gum Lichen (Lecanora muralis). I saw this species colonizing sun-exposed areas of Catch Rock; the patches I observed were more chaotic, less rosette-formed, and lacked the foliose-looking lobes of its more squamulosed neighbour, the Chewing Gum Lichen. This lichen is also very similar to another rock-dwelling lichen, Rhizoplaca opiniconensis, which, however, prefers shaded rock faces near streams.

.

Zoned Dust Lichen (Lepraria neglecta)

Zoned Dust Lichen (Lepraria neglecta): As the species name of this lichen suggests, this tiny granular fuzzy lichen that looks like so much dust, is often neglected because of its diminutive size and chaotic presentation. Walewski writes that dust lichen “are nothing more than a continuous layer of granular soridia.” Zoned Dust Lichen commonly grows on partially shaded granitic rock; I found it hiding among more robust lichen on the rock face, both shaded and exposed to the sun. Once established, Zone Dust Lichen often forms distinct rings.

.

Sulphur Firedot (Caloplaca flavovirescens) and Common Goldspeck (Candelariella vitellina)

I saw one or both of these lichen on the granite surface amid other larger lichens that I photographed. In all cases, I only saw them in post-production among the rock crystals. They were so small and rare that I missed seeing them with the naked eye. Both of these tiny crustose lichen are common and live on granite rock. Common Goldspeck prefers sun-exposed areas, which is where I found it. Walewski notes that these two very common lichens are frequently overlooked. He advises to check for them amid the more robust foliose lichens.

.

References:

Ahmadjian, V. 1993. “The Lichen Symbiosis.” Wiley, New York.

Ascaso, C. and J. Wierzchos. 1994. “Structural aspects of the lichen-rock interface using back-scattered electron imaging.” Bot. Acta. 107: 251-256.

Barmen, A.K., C. Varadachari, K. Ghosh. 1992. “Weathering of silicate minerals by organic acids: I. Nature of cation solubilization.” Geoderma 53:45–63.

Barrett, David. 2021. “Canadian Shield.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Original entry February 7, 2006; edited August 11, 2021.

Brodo, Irwin M., Sylvia Duran Sharnoff and Stephen Sharnoff. 2001. “Lichens of North America.” Yale University Press, New Haven. 795pp.

Chen, Jie, Hans-Peter Blume, Lothar Beyer. 2000. “Weathering of rocks induced by lichen colonization—a review.” Catena 39(2): 121-146.

Daxberger, Heidi. 2022. “Introduction to the Geology of the Central Metasedimentary Belt.” In: Atlas of the Central Metasedimentary Belt Bedrock Geology in Southern Ontario. Ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub.

Deduke, Chris, Norman M. Halden, and Michele D. Piercey-Normore. 2016. “comparing element composition of rock substratum with lichen communities and the fecundity of Arctoparmelia and Xanthoparmelia species.” Botony 94(1):

Easton, R.M. 2010. “Precambrian geology of Cavndish Township and environs, Grenville Province; Ontario Geological Survey, Preliminary Map P.3605, scale 1:20 000.”

Easton, R.M. 2012. “Precambrian Geology of Cavendish Township, Central Metasedimentary Belt, Grenville Province.” Ontario Geological Survey Open File Report 6229. 142pp + appendices.

Farkas E., Biró B., Szabó K., Veres K., Csintalan Z., Engel R. 2020. “The amount of lichen secondary metabolites in Cladonia foliacea (Cladoniaceae, lichenised Ascomycota).” Acta Botanica Hungarica 62: 33-48.

Fry, E.J. 1924. “A suggested explanation of the mechanical action of lythophytic lichens on rocks (shale). Ann. Bot. 38: 175-196.

Fry, E.J. 1927. “The mechanical action of crustaceous lichens on substrata of shale, schist, gneiss, limestone and obsidian.” Ann. Bot. 40:437-460.

Galloway, D.J. 1994. “Biogeography and ancestry of lichens and other ascomycetes.” In: Hawksworth, D.L. (ed.) “Ascomycete Systematics. Problems and Perspectives in the Nineties.” Plenum, New York. pp.175-184.

Hale, Mason E. 1967. “The Biology of Lichens.” Edward Arnold Ltd., London. 176pp.

Hawksworth, David L. and Francis Rose. 1977. “Lichens as Pollution Monitors” Edward Arnold Ltd., London. 60pp.

Honegger, R. 1993. “Development biology of lichens” New Phytol 125: 659-677.

Iskandar, I.K. J.K. Syers. 1972. “Metal-complex formation by lichen compounds.” J. Soil Sci. 23: 255-265.

Jung, P. et. al. 2020. “Lichens Bite the Dust—A Bioweathering Scenario in the Atacama Desert.” iScience 23(11)

Kershaw, Kenneth A. 1985. “Physiological ecology of lichens.” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, London. 293pp.

Larson, D.W. 1987. “The absorption and release of water by lichens.” In Peveling, E. (ed.) “Progress and Problems in Lichenology in the Eighties.” Bibiothca lichenological 25 J. Cramer, Berlin, pp. 351-360.

Murray, Alexander, Harrisson Panabaker; Holy O’Rourke; David Barrett. 2006. “Canadian Shield”. The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Noh, Hyun-Ju, Yung Mi Lee, Chae Haeng Park, Hong Kum Lee, Jang-Cheon Cho, Soon Gyu Hong. 2020. “Microbiome in Cladonia squamosa Is Vertically Stratified According to Microclimatic Conditions.” Front. Microbiol. 25(11): 268

Prieto Lamas, B. M. T. Rivas Brae, B.M. Hermo Silva. 1995. “Colonization by lichens of granite churches in Calacia (northwest Spain)”. Sci. Total Environ. 167: 343-351.

Prieto, Lamas, B. Silva, T. Rivas, J. Wierzchos, C. Ascaso. 1997. “Mineralogical transformation and neoformation in granite by lichens Tephromela atra and Ochrolechia parella.” Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 40: 191-199.

Purvis, William. 2000. “Lichens.” Natural History Museum, London. 112pp.

Rao D.N., LeBlanc F. 1965. “A possible role of atranorin in the lichen thallus.” The Bryologist 68: 284-289.

Seaward, M.R.D. 1997. “Major impactS made by lichens in biodeterioration processes.” Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 40: 269-273.

Silva, B., B. Prieto, T. Rivas, M.J. Sanchez-Biezma, G. Paz, and G. Carballal. 1997. “Rapid biological colonization of a granitic building by lichens.” Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 40: 263-267.

Silva, B., T. Rivas, and B. Prieto. 1999. “Effects of lichens on the geochemical weathering of granitic rocks.” Chemosphere 39(2): 379-388.

Taylor, T.N., H. Hass, W. Remy, & H. Kerp. 1995 “The oldest fossil lichen.” Nature 378(244):

Wierzchos, J. and C. Ascaso. 1996. “Morphological and chemical features of bioweathered granitic biotite induced by lichen activity.” Clays Clay Miner 44: 652-657.

Wong, Pak Yau and Irwin M. Brodo. 1992. “The Lichens of Southern Ontario, Canada.” Canadian Museum of Nature, Syllogeous No. 69. 79pp.

Zraik M., Booth T., Piercey-Normore M.D. 2018. “Relationship between lichen species composition, secondary metabolites and soil pH, organic matter, and grain characteristics in Manitoba.” Botany 96: 267-279.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

14 thoughts on “The Lichen Forest of Catch Rock”