I’m an ecologist and limnologist (someone who studies water systems). But I’m a writer too. I write novels and short stories and lots of articles on nature and science for various magazines including my own sites. I walk almost daily in the local forests and by the river near my place and write about my adventures there. So, when I encountered lichens that ‘write’ I was more than intrigued. What? You don’t believe that lichens can write? Well, read on…

Lichens that Write

.

It was a warmish day in early fall as I was walking through the lowland mixed beech-hemlock stand in the Mark S. Burnham old-growth forest. I was studying an old beech tree and chanced on some interesting growths on a neighbouring young beech tree. It looked like pale green to grey paint and was covered in black dots like bits of soot. I surmised that the powdery ‘paint’ was one of the crustose dust lichens (e.g., Lepraria or Lecanora) that like to colonize trees. On closer inspection, I saw that the black ‘dots’ were in fact dark squiggles, concentrated at the centre of the grey-white smear of leprose (powdery) lichen (the thallus). The dark squiggles, raised like tiny eskers, resembled hieroglyphs, strange symbols, scrawled there in cryptic code like the poetry of shy forest sprites. My first thought was that these dark squiggles were a parasitic fungus or some insect egg infestation on the crustose patch of grey-green lichen; the latter was a stretch considering the strange patterns of the markings.

When I returned home and did more research, I discovered that the mysterious markings were in fact the raised fruiting bodies (apothecia) of the Common Script Lichen (Graphis scripta), a pale green-grey crustose and leprose lichen that prefers smooth bark on which to write its stories.

Common Script Lichen (Graphis scripta)

The apothecia of Graphis scripta aren’t always visible, becoming more prominent in late fall and winter. I was lucky to see them. These lichens start rather inconspicuously as green-grey smears on a tree, eventually developing visible squiggles of apothecia (elongated, branched fruiting bodies) that may look like a pair of lips, called lirellae. During my winter excursions in several nearby forests I’ve seen the Common Script Lichen on the smooth bark of young red and sugar maple, alder and poplar trees.

.

There are many species of Script Lichen in the Graphis genus. Wikipedia lists a few hundred of them, most with squiggly apothecia. Other literary lichens include the Scribble Lichens (e.g., Opegrapha), Comma Lichens (e.g., Chrysothrix, Arthonia, Arthothelium), Asterisk Lichens (Arthonia) and the Dot Lichens (e.g. Arthonia or Micarea) which should be named Period Lichens, if you ask me.

.

But here’s the thing.

While Graphis scripta is busy colonizing maple or poplar bark, another lichen is busy growing on it! Graphis scripta is a common host to the lichenicolous Arthonia graphidicola, a lichen without a thallus whose apothecia (fruiting bodies), which resemble G. scripta apothecia, colonize the host thallus then erupt through the host’s thallus—somewhat like the alien in Alien, though without the devastating mess left behind (as in a dead eviscerated human). The apothecia of A. graphidicola, which appear as rounded, many-sided, or elongated structures, are difficult to distinguish from the host’s own apothecia, which is bizarre and reminds me of the cuckoo bird that parasitizes a wren’s nest by dropping off its look-a-like egg, which the wren looks after, often at the expense of its own.

I’m not making all this up; go see the British Lichen Society. Some researchers suggest that the apothecia of A. graphidicola are smaller and less elongated or elaborate as those of G. scripta (check out the image below for comparison). This lichenicolous lichen may also show its presence by staining the thallus of its host pink. I may have witnessed that before I learned about this interesting tell.

.

.

A lichenicolous lichen is basically a lichen that grows on or in another lichen. Diederich et al. (2018) estimated over 2,000 species worldwide of lichenicolous fungi—many that evolve into lichen once they colonize a host—known to live on lichens as host-specific parasites, pathogens, saprotrophs and commensals. Lichenicolous lichens are considered a subset of this group with a few hundred species recognized so far. According to Knudsen (2013) lichenicolous lichen have a two-stage cycle. Many start as juvenile non-lichenized fungal parasites which then develop into a lichen by stealing an algal partner from the host lichen. More on this delightful process in another article.

Nimis et al. (2024) suggest that at least some lichenicolous lichen are not true “parasites”, as they are often called, but gather their algal partners (photobionts), which have already adapted to local ecological conditions, from their hosts, and eventually develop an independent thallus.

So, in the end, I may have been right after all in thinking the black marks were a fungal parasite. They still might be! I’m reminded of Augustus De Morgan’s famous ditty about fleas and thought I would adapt it for lichens:

Big lichen have little lichen upon their backs to mine them, and little lichen have lesser lichen, and so ad infinitum.

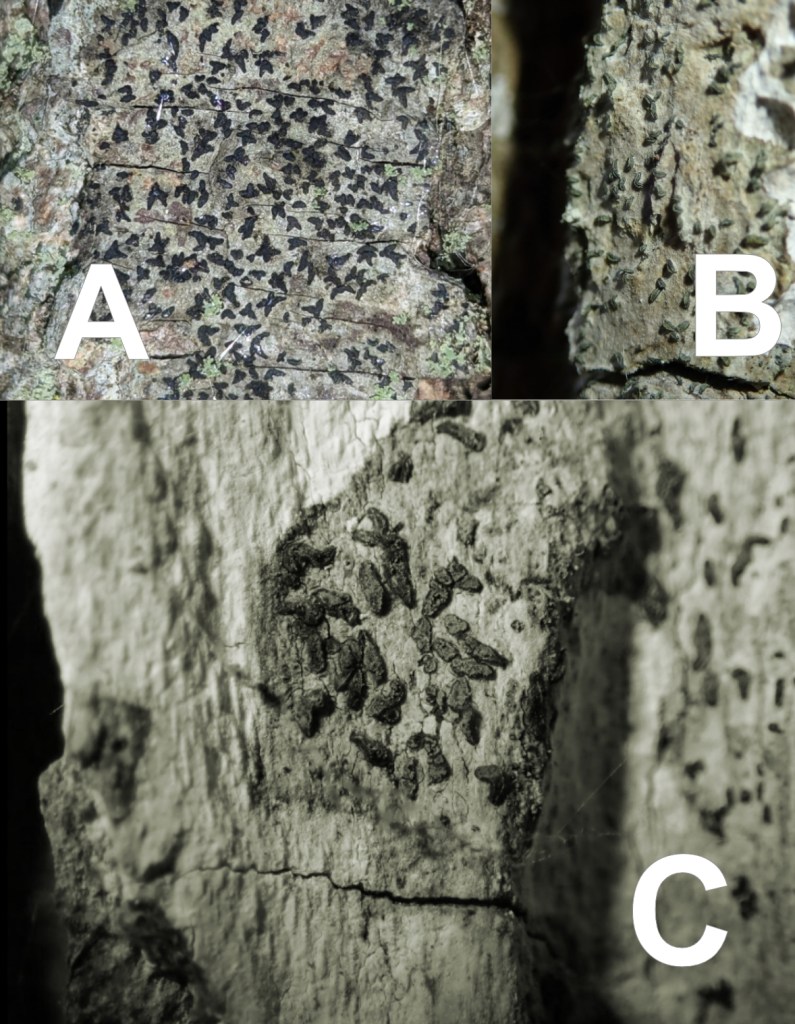

Bark Scribble Lichen (Alyxoria varia)

.

Another writing lichen is the Bark Scribble, Alyxoria varia, previously classified in the genus Opegrapha. The site iNaturalist.org tells us that Alyxoria varia “is thought to represent a complex of species with uncertain phylogenetic placement.” All to say that the jury isn’t out yet and it may change its name again. Its common name, scribble lichen, refers to the form of its ascomata (fruiting bodies) that are long or short, sometimes branched with blackened walls and bases. The thallus of Bark Scribble is hidden mostly within the bark itself. Fungi of Great Britain and Ireland tell us that this writing lichen is most frequently found on the shaded neutral to basic rough bark, especially of oak, maple and elm. I spotted what I think is this lichen on an old maple tree in a mixed forest.

.

.

Lichens that Punctuate

Lichens don’t just write ‘words’; they also punctuate. As with word-use there are numerous commas (comma Llchen), periods (button and dot lichen) and even asterisks (asterisk lichen). Some lichens even map. Those I’ve encountered are included below.

.

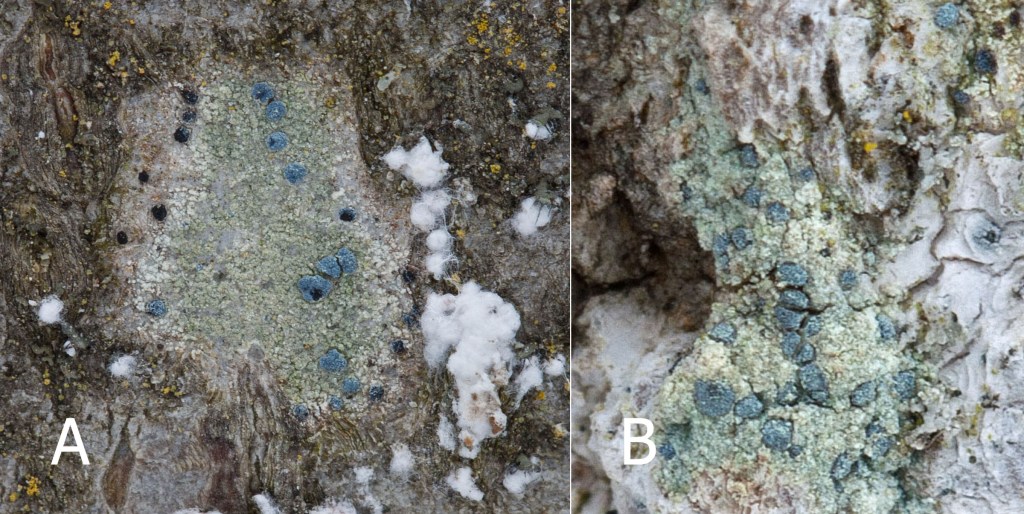

Frosted Comma Lichen (Chrysothrix caesia)

.

I found this lichen growing on a young red maple in the Trent Forest in mid-winter. Known to prefer exposed bark near water, where I found it, this lichen forms a small dime- or quarter-sized whitish-to-pale-green-yellow granular thallus with ‘frosted’ pruinose blue fruiting bodies (called ascomata on this lichen). Apparently, it only fruits in winter, so I was seeing its best face. Its photobiont is a coccal green alga.

.

Aspen Comma Lichen (Arthonia patelluta)

.

I found the Aspen Comma Lichen on … you guessed it … an aspen tree, likely a Trembling Aspen (Populus tremuloides), in the Trent Forest. This crustose lichen had a powdery whitish thallus and black ‘frosted’ pruinose mostly roundish black dots that looked more like ‘periods’ than ‘commas’; these are the fruiting bodies (called ascomata on this lichen). The Aspen Comma Lichen prefers the smooth bark of younger poplar (Aspen) trees, forming a very thin grey-white thallus and rounded black apothecia.

.

Comma Lichen (Arthothelium spectabile)

.

I found this comma lichen on several maple trees, mostly young ones. At least this comma lichen looks a little more like a ‘comma’, with a whitish powdery thallus on which are scattered tiny black not quite round ‘frosted’ epruinose fruiting bodies. This lichen is known to prefer the bark of hardwood trees. Italic 8.0 describes this lichenicolous species as having a crustose thallus, mostly endosubstratic (living inside the substrate whether bark or lichen), effuse, greyish white to greenish grey and with apothecia that are rounded or angular and black epruinose, slightly convex rough disk. Its algal partner is Trentepohlia.

.

.

Asterisk Lichen (Arthonia radiata)

.

The Asterisk Lichen, whose fruiting bodies (apothecia) in fact resemble an asterisk, is a common and widespread corticolous lichen that prefers the smooth bark of many young trees and shrubs. According to iNaturalist, Its pale white to grey thallus forms a mosaic-like pattern on the bark, often separated from its surroundings by a thin brown line (see photo below). The tiny black ‘unfrosted’ apothecia (fruiting bodies) are star-like (stellate), round or elongated.

.

.

Lichens that Map

.

If we push the narrative to include illustration and mapping, we have the Yellow Map Lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum), a saxicolous lichen that I found colonizing a granite outcrop in the wetland of Catchacoma old-growth forest, Ontario. Yellow Map Lichen is normally found on silicate rocks. Lichenologist William Purvis describes them as “minute yellow green islands, which contain the pigment rhizocarpic acid, growing on a black layer lacking algae.” The black edging of the thallus is called the prothallus, a fungal layer that advances out and contains allelopathic chemicals to ward off competitors.

There is something strangely invigorating about the thought of lichen that express themselves. A kind of gestalt presence, a genius that defies Cartesian epistemology. Nature winking. The Natur und Kunst of Goethe’s naturphilosophie.

.

“Nature! We are surrounded and embraced by her; powerless to separate ourselves from her, and powerless to penetrate beyond her … We live in her midst and know her not. She is incessantly speaking to us, but betrays not her secret. … She has always thought and always thinks; though not as man, but as Nature. … She loves herself, and her innumerable eyes and affections are fixed upon herself. She has divided herself that she may be her own delight. She causes an endless succession of new capacities for enjoyment to spring up, that her insatiable sympathy may be assuaged. … The spectacle of nature is always new, for she is always renewing the spectators. Life is her most exquisite invention; and death is her expert contrivance to get plenty of life.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

.

References:

Deiderich, P., JD. Lawrey, and D. Ertz. 2018. “The 2018 classification and checklist of lichenicolous fungi with 2000 non-lichenized, obligately lichenicolous taxa.” The Bryologist 121(3): 340-425.

Friedl, T. 1987. “Thallus development and phycobionts of the parasitic lichen Diploschistes muscorum.” Lichenologist 19(2): 183-191.

Knudsen, Kerry, John W. Sheard, Jana Kocourkova, and Helmut Mayrhofer. 2013. “A new lichenicolous lichen from Europe and western North America in the genus Dimelaena (Physciaceae).” The Bryologist 116(3): 257-262.

Nimis, Pier Luigi, Elena Pittao, Monica Caramia, Piero Pitacco, Stefano Martellos, and Lucia Muggia. 2024. “The ecology of lichenicolous lichens: a case-study in Italy.” MycoKeys 105: 253-266.

Purvis, William. 2000. “Lichens.” Natural History Museum, London. 112pp.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

2 thoughts on “Scholarly Lichen: When a Lichen Writes…”