.

The American Beech tree (Fagus grandifolia) is one of my favourite trees. It’s not as stately or majestic as the tall oak tree or even the gnarly many-branched maple. This slender tree commands incredible grace and beauty with a proud smooth grey trunk that resembles slate more than wood. There is something rather elegant, even mysterious, about this handsome tree that stands singularly pale and smooth in an umbrous rough crowd—a tree that stubbornly holds onto its copper-coloured leaves in the cold of winter (called marcescence), long after its hardwood neighbours have given up theirs.

.

.

Alas, its smooth blue-grey bark is a magnet to juvenile lovers and graffiti vandals, compelled to mark up that ‘empty’ canvas presented to them—and unaware that this harms the tree by inviting disease and pests.

.

.

According to Peter Wohlleben, German forester and author of The Hidden Life of Trees, beeches are particularly social in their growth; older trees share nutrients via their root systems with younger saplings, and surrounding beeches pump sugar to a stump to keep it alive so it can continue to provide other essentials to the community. Young beech saplings, growing beneath the shade of adult trees receive sugars from their mother trees through their roots. He adds that beeches last barely more than two hundred years outside their native forests [where they can live to 400 years old among other beeches], while oaks growing near old farmyards or out in pastures can live for more than five hundred. Even severely damaged oak trees with major branches broken off can grow replacement crowns and live for a few hundred years longer. “A storm-battered beech is able to hang on for no more than a couple of decades.”

300-year old beech grows tall among hemlocks in Mark S. Burnham Forest, ON (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

.

Under more ideal conditions, the beech out-competes the oak for more light by achieving a higher crown through rapid growth. Its young saplings can also tolerate less light over other trees like the oak, which is why the beech does so well in a dark hemlock forest.

Beech trees even practice a kind of “socialism versus capitalism” by synchronizing their photosynthesis: “equalizing between the strong and the weak and ensuring that all are equally successful.” Whoever has an abundance of sugar shares; whoever needs sugar receives from others. The beech epitomizes the opposite of neoliberal capitalism by growing together in community, sharing nutrients and water that are “optimally divided among them so that each tree can grow into the best tree it can be,” writes Wohlleben.

.

If the forest was Europe, the beech tree would be France: beautiful, graceful, fashionable; gaggling together in social circles like French poets discussing politics in a café.

In the wild, the American beech tree (Fagus grandifolia) grows up to 120 feet high and can live to three hundred years, possibly more–often still retaining its handsome youthful bark. But more often, when a beech tree reaches middle age (past 80 years), its bark starts to wrinkle, starting from the bottom up. ArbTalk suggests that the older beech tree does this in a response to attacking scale insects by adding additional protective bark. Moss, algae and lichen colonize the trunk’s nooks and small crevices, where moisture from recent rains linger.

The beech reaches sexual maturity at 80 to 150 years of age. Such a tree may only be person-height with a diameter of your thumb. This is partially because once the beech sapling establishes, its growth is subdued by the shaded canopy of its mother trees. Wohlleben suggests counting the small yearly growth nodes on a branch of a young beech to count the growth years. Using this approach, Wohlleben noted that a seven foot high one-inch diameter European beech (Fagus sylvatica) in the German forest he was caretaking was already well over 25 years old.

.

Over time, beech trees clothe their feet in thick socks of moss and liverworts; little else seems to grow on the bark of its trunk. But closer inspection reveals a whole understated world: a complex ecosystem of miniature moss forests, trailing liverworts and splashes of lichen, all creating filigrees of latticed texture, colour and shade that clothe the beech trunk and branches in subtle notes of pale green or grey-white that often complement the beech’s own bark colour and texture. Lichen that grow on bark (referred to as corticolous) are mostly crustose or small foliose lichen, flat and tightly appressed against the bark. Bryophytes and mosses add a little green to the grey bark.

.

.

The beech trees in the Mark S. Burnham Old-Growth Forest can be quite old with thick trunks that stretch their pale limbs to pierce the overstory over 30 metres high. Several beech trees are well over two hundred years old. They have every right to be gnarly, grumpy and rough. As beech trees age, this is exactly what happens. Even without the onslaught of various diseases that cause cankers and splits in the smooth bark, old beech trees develop rough bark, with wrinkles, ripples and cracks and warts, often clothed in thick moss, liverworts and, of course, lichen. And the lichen I found—mostly crustose—varied from tiny purple-black dots on the oil-slick mosaics of pox lichen to script lichen’s dark blue squiggly hieroglyphics on whitish-grey parchment.

.

Örjan Fritz and colleagues, who documented lichen and bryophytes growing on mature European beech trees (Fagus sylvatica), tell us that tree age exerts a profound influence on epiphytic lichens and bryophytes; they observed a significant increase in lichen diversity as the trees aged. Many lichens favoured older beeches for their richer varied substrates that included rain tracks, crevices, rot holes and sap flows. In Europe, these lichen are at risk due to conventionally managed beech forests and many are red-listed. The researchers also noted that damaged trees and their particular bark quality provided an important substrate for certain lichen. All to imply that management strategies, including short rotation forestry, that include removal of old trees, negatively impact growth of lichen and bryophyte epiphytes.

.

My Two Old Beech Trees

I singled out two particularly well-girthed beech trees for closer inspection and documented what was growing on their trunks (see Table 1 at the end of the article).

.

.

150-year old American Beech: the first large American Beech (Fagus grandifolia), about 110 m north of the entrance and well into the hemlock forest, had a dbh (diameter at breast height) of 59 cm, putting it at 100-150 years old; though beech trees with this dbh can be as old as 250 years (for instance, a beech tree with 51 dbh in the Backus Woods of Ontario (off Lake Erie) was aged through core at 204 years). Despite its considerable girth this beech retained its smooth slate grey bark, though with some ripples and warts. Bright green mossy socks were weaving themselves over its feet, particularly on its north side. Wohlleben tells us that you can estimate the age of a beech tree by observing how far up the green growth is on the trunk. Another way is by observing how wide the tree has become. Wohlleben notes that, just like people, trees stop growing tall and instead get wider with age. Taken together, these characteristics support my age estimate from the tree’s dbh at slightly over middle-age.

.

.

300-year old American Beech: the second and much wider beech, located deeper in the wet swamp hemlock-cedar forest had a 89 cm dbh, which places it around 300 years old. American beeches have a long lifespan, commonly living to 250 years, but frequently reaching over 300 years old, and a few exceeding 400 years with 90 cm dbh (close to my beech). The 300-year old beech tree is considered ancient and looks it, with cracked and gnarled bark, some hollow branches, and thick moss socks covering its feet and rising up the trunk.

For a 300 year-old tree, this beech still looks good, with sturdy trunk, thick leafy branches and many young beeches surrounding it. Given that some beeches can live to 400 years, this one is cranking away at achieving this milestone and I’m cheering it on.

.

What Grows on the 150-year old Beech Tree

.

The feet of the 150-year old beech tree were sparsely clothed with bryophytes, dominated by Feather Moss and Tree Ruffle Liverwort. Shingle Moss (Neckera complanata) confined itself mostly to the tree’s feet in community. Feather Mosses and Bristle Mosses formed snaking lines along the trunk from the feet of the tree; the upper trunk was dominated by New York Scalewort (Frullania eboracensis), which formed large fist-sized rosettes, together with patches of Flat-leaved Scalewort (Radula complanata) and Tree Ruffle Liverwort (Porella navicularis).

.

.

Lichen

.

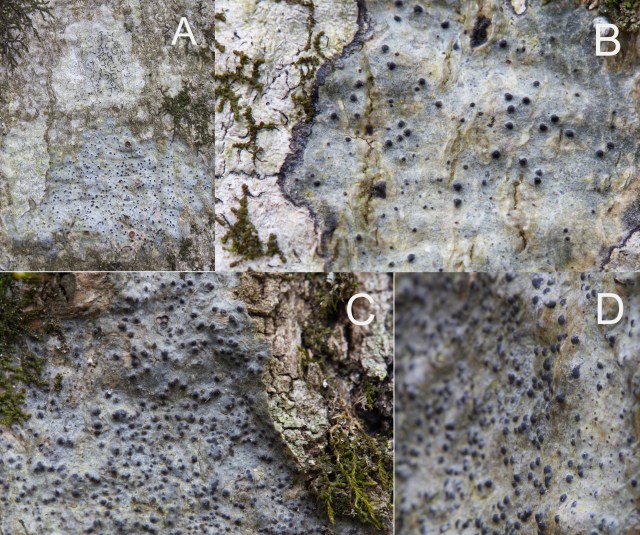

The trunk of the old beech was covered, literally, in crustose lichen. Though not obvious at first, close inspection revealed a sweeping wash of whitish to grey thalli and tiny dots spread all over the trunk. Most of these were a combination of several lichen, dominated by Common Script Lichen (Graphis scripta), Common Scribble Lichen (Opegrapha vulgata), Bark Scribble Lichen (Alyxoria varia) and the Comma Lichen, Arthonia exipienda, which covered large areas of bark, particularly near the tree base. Common Script Lichen (Graphis scripta) formed tooney-sized grey-whitish patches throughout the trunk. The blue- black squiggles on whitish-grey ‘parchment’ looks like an ancient hieroglyphic language yet to be deciphered. Perhaps the poetry of some fairy or tree sprite. The squiggles are the apothecia (fruiting bodies) and the parchment is the lichen thallus or body. According to Fritz et al. this writing lichen typically establishes after the tree has reached several decades and persists and remains a resident until the tree is close to 200 years old. Opegrapha vulgata shows a colonization time that closely overlaps Graphis scripta; Opegrapha appears on a tree at around 125 years and disappears at 225 years.

The ‘parchment’ or thallus of Graphis scripta is often host to other lichens (called lichenicolous) that use it to make their edits (often a simpler version of the Graphis script) with their own apothecia. Bark Scribble Lichen (Alyxoria varia) and the Comma Lichen (Arthothelium spectiabile) commonly use G. scripta as a host thallus. The reproductive structures of these comma lichens are called discs that resemble apothecia; they are red-brown to black in color and can be flat, convex, elongated, or star-like—all shapes that I saw. The Bark Scribble Lichen (Alyxoria varia), previously classified in the genus Opegrapha, is appropriately called ‘scribble’ from its squiggly and varied ascomata (fruiting bodies).

.

.

The Asterisk Lichen (Arthonia radiata), whose fruiting bodies (apothecia) in fact resemble an asterisk, is a common and widespread corticolous lichen that prefers the smooth bark of many trees and shrubs. According to iNaturalist, Its pale white to grey thallus forms a mosaic-like pattern on the bark, often separated from its surroundings by a thin brown line (see photo below). The tiny black ‘unfrosted’ apothecia (fruiting bodies) are star-like (stellate), round or elongated.

.

.

I also observed patches of Common Button Lichen (Buellia erubescens), spreading like paint splashes over the beech bark, and dotted with dark, almost black, ‘buttons.’ This crustose lichen is often found on conifers and oaks and other trees with bark of generally low pH (e.g. my old beech tree).

.

.

The Comma Lichen, Arthonia excipienda was scattered throughout the beech trunk, forming dense colonies in some cases of little bean-shaped black-brown naked apothecia that resembled lips. Italic 8.0 describes this corticolous crustose lichen as having an endosubstratic thallus (e.g. invisible because it lies inside the bark) with arthonioid (without a true margin) and mostly lirelliform apothecia (fruiting bodies that are “lip-shaped”—elongated, straight or curved, rarely branched, with a furrow or ridge running down their middles).

I also noticed small patches of City Dot Lichen (Scoliciosporum chlorococcum) scattered on the bark surface. This lichen is known to prefer the damp, shaded, nutrient-rich bark of older trees. Italic 8.0 notes that the City Dot Lichen is ecologically wide-ranging and normally found on bark (corticolous) especially Beech.

.

.

Several small dark patches that resembled iridescent oil-slicks with purple edging and purple smears and dots added dramatic colour. I identified these small colonies as Enterographa crassa, another script lichen. Common on old beech trees, its thin thallus is known to form complex refractive mosaic smears from pale grey or brown to dark olive green with visible prothallus here and there.

.

.

Other larger oil-slick lichen, with distinct purple-to-black raised ‘pimples’ in a sea of pale olive green or lilac, was edged with dark purple where it met another crustose lichen. The colonies often bordered Script Lichen or other writing lichen, creating suture lines between them and forming a complex mosaic patchwork pattern. I later identified these colourful lichen as Easter Pox Lichen (Pyrenula pseudobufonia), a common lichen known to colonize veteran beech trees. They are most common in eastern North America and, according to the Ottawa Field-Naturists’ Club, frequent in southern Ontario. The greenish hue and streaks are likely from the algal partner, Trentepohlia. I observed another lichen very similar to the Easter Pox Lichen, which I determined was Acrocordia gemmata (not pictured) It also colonizes old beech bark and other rough bark of mature broadleaved trees.

.

.

The dark edged margins or suture lines between various crustose lichen are the leading fungal hyphae layer (prothallus) located beneath the thallus of the lichen; they act as an anchoring system and help create an allelopathic border against competing lichen. Cracks also develop in older crustose lichen as the fungal part splits, just like asphalt or old paint cracks, forming smaller ‘islands’ called areolas. The cracks can be affected by temperature and humidity changes and the lichen’s own metabolic processes.

The only foliose lichen I observed was the very common and ubiquitous Pom Pom Shadow Lichen (Pheaophyscia pusilloides), with its telltale dark rhizines. It is a common lichen on deciduous trees with nutrient-rich bark; I’ve observed it growing on beeches, oaks, ash, ironwoods, poplars, maples, and birches.

.

.

Mosses & Liverworts

.

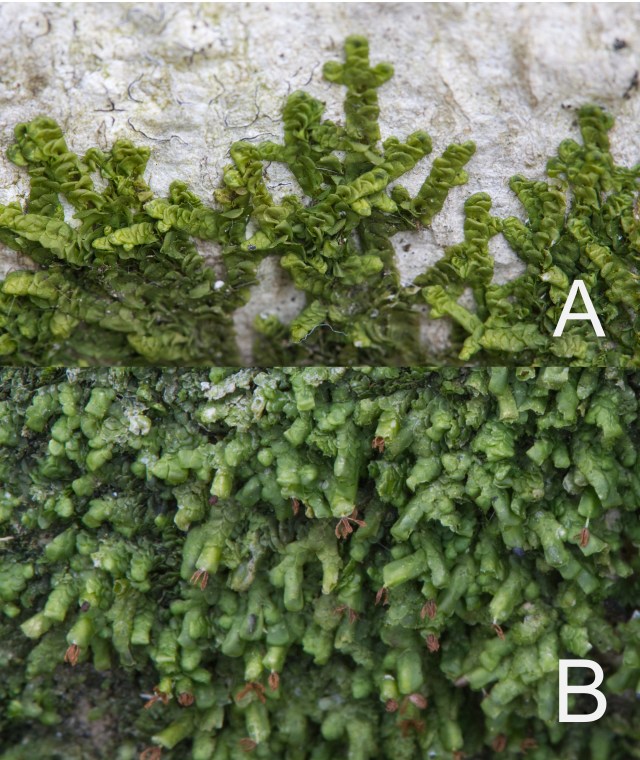

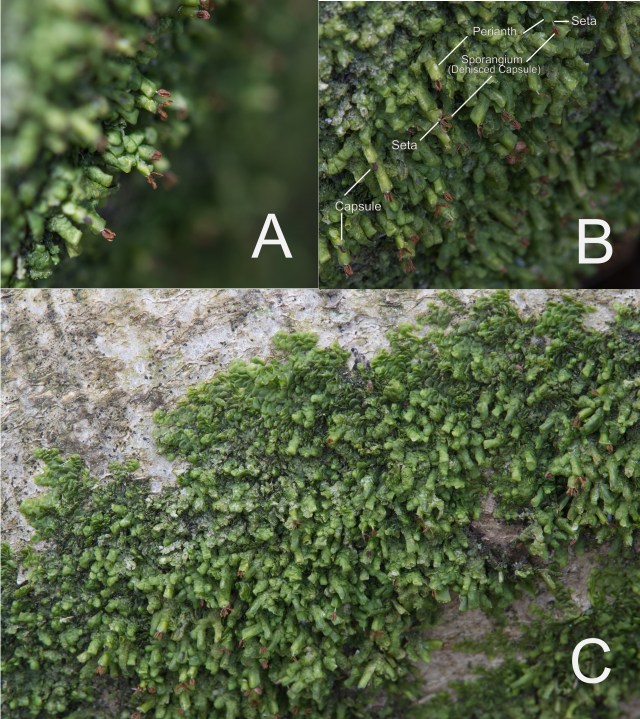

Shingle Moss (Neckera pennata) confined itself mostly to the tree’s feet in community with Feather Moss (Brachythecium spp.) and Tree Ruffle Liverwort (Porella navicularis). Climbing up from the feet of the tree high along the trunk, were mostly feather mosses, bristle mosses, pincushion mosses and several liverworts dominated by New York Scalewort (Frullania eboracensis) forming large fist-sized rosettes, and Flat-leaved Scalewort (Radula complanata), snaking up the tree trunks.

.

.

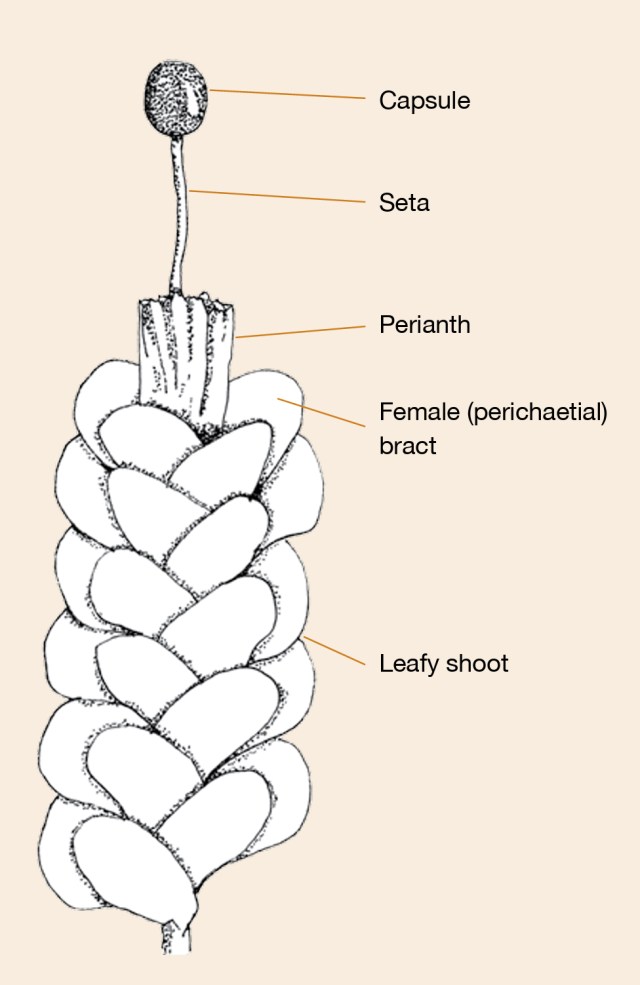

Radula complanata is a pale yellowish-green liverwort growing flattened against the bark with ribbon-like leaves, arranged in overlapping rows; raised rectangular perianths of modified leaves (tube-like tissue surrounding the female reproductive organs and developing sporophytes) can often be seen.

.

.

Flat-leaved Scalewort is often found in damp, shaded areas, and plays a significant role in nutrient cycling and carbon fixation. When I had a closer look at this creeping plant, I noticed bluish and brown ‘blobs’ extending from the rectangular perianths. These I later learned were the capsules of sporophytes emerging from the fertile gametophyte to release spores when mature. The short seta elevates the sporangium above the perianth and when mature, the sporangium dehisces (splits open) along four lines of weakness in the capsule wall to disperse spores. Within the capsule, elators (tubular cells with spiral thickenings) help release the spores.

.

.

What Grows on the 300-year old Beech Tree

.

The base of the 300-year old beech tree was covered in thick skirt of bright green bryophytes. Bryophytes included: Fern Moss (Thuidium delicatulum), Shingle Moss (Neckera pennata), Feather Moss (Brachythecium spp.), Tree Ruffle Liverwort (Porella navicularis) and Flat-leaved Scalewort (Radula complanata).

.

.

Apart from its thickly-covered base, the heavily scaled and cracking bark of the main trunk had much less growth on its highly ridged and rough trunk than the smoother 150-year old beech. The bark was deeply furrowed with crevices and a general roughness resembling sand paper. It seemed to be peeling layer upon layer. Large pits where the bark had been eaten into the deeper cork layer made significant craters, creating a strange brittle moonscape.

.

.

Lichen

.

I found small whitish patches of Common Script Lichen (Graphis scripta), and Common Scribble Lichen (Opegrapha vulgata) and Bark Scribble Lichen (Alyxoria varia) near the base of the tree, mostly on the south and west aspects.

Fritz and colleagues noted that red-listed lichens increased dramatically when tree age exceeded 180 years, occupying over two-thirds of all branches. They documented many crustose lichen species that grew only on the rough bark of beech trees over 200 years of age (e.g. Bacidina phacodes, Pachyphiale carneola and Thelopsis rubella). I found none of these on my ancient beech tree.

.

Mosses & Liverworts

.

Flat-leaved Scalewort (Radula complanata) wandered up from the tree’s feet, accompanied by New York Scalewort (Frullania eboracensis), Bristle Moss (Orthotrichum spp.) and Pincushion Moss (Ulota crispa) at eye-level and higher. Looking up the trunk, I saw mosses and liverworts reaching up its considerable height. Mostly Bristle and Pincushion moss and Scalewort.

.

Vertical Distribution Along a Tree

Both trees showed vertical stratification, with mosses and liverworts concentrated at the tree base and some lichens more obvious as one moved up the tree or on upper branches.

This makes sense. Joe Walewski tells us that older trees have a greater diversity of lichens. Walewski notes that, while the Hoary Rosette Lichen (Physcia aipolia) increases up the trunk of a tree, the Hooded Rosette Lichen (Physcia adscendens) decreases in abundance. This may have something to do with light conditions or more likely nutrient conditions of the tree. The British Lichen Society mentions that Physcia adscendens is very common on nutrient enriched tree bark, often forming luxuriant colonies along rain tracks on tree trunks. Its preference for lower older bark likely relates to how older cracked bark leaches out alkaline nitrogenous compounds.

.

Jerry Jenkins’s excellent moss guide for old trees in northern forests showcases the vertical colonization by the most common mosses and liverworts growing from the base ‘skirt’ up the height of the tree. My observations closely matched his list and graphic portrayal of moss colonization of an older tree.

*Porella is the Tree Ruffle Liverwort; all others are mosses

Vertical stratification of common mosses on an old tree (image from Jenkins, 2020)

.

References:

Churski, Marcin and Mats Niklasson. 2010. “Spatially and temporally disjointed old-growth structures in a southern Swedish beech dominated forest landscape.” Ecological Bulletins 53: 109-115.

Fritz, Örjan, Mats Niklasson, and Marcin Churski. 2008. “Tree age is a key factor for the conservation of epiphytic lichens and bryophytes in beech forests.” Applied Vegetation Science 12: 93-106.

Jenkins, Jerry. 2020. “Mosses of the Northern Forest: A Photographic Guide.” Comstock Publishing Associates, Cornell University Press, Ithaca. 169pp.

Tubbs, Carl H. and David R. Houston. 1990. “Fagus grandifolia.”

Walewski, Joe. 2007. “Lichens of the North Woods.” Kollath & Stensaas Publishing, Duluth, MN.

.

| Table 1: Lichen & Bryophytes Found on 150-year old Beech and 300-year old Beech in Mark S. Burnham Forest, Spring 2025 | ||||

| LICHEN & BRYOPHYTES | BEECH | |||

| COMMON NAME | LATIN NAME | 150 yr | 300 yr | |

| LICHEN | Common Script Lichen | Graphis scripta* | xx | x |

| Bark Scribble Lichen | Alyxoria varia* | xx | x | |

| Common Scribble Lichen | Opegrapha vulgata | x | x | |

| Comma Lichen | Arthothelium spectiabile | x | ||

| Easter Pox Lichen | Pyrenula pseudobufonia* | xx | ||

| No common name | Acrocordia gemmata | x | ||

| Script Lichen | Enterographa crassa* | x | ||

| Comma Lichen | Arthonia excipienda* | xx | ||

| Asterisk Lichen | Arthonia radiata* | x | ||

| Common Button Lichen | Buellia erubescens* | x | ||

| City Dot Lichen | Scoliciosporum chlorococcum* | x | ||

| Pom Pom Shadow Lichen | Pheaophyscia pusilloides* | x | x | |

| MOSS | Shingle Moss | Neckera pennata* | x | x |

| Fern Moss | Thuidium delicatulum* | xxx | ||

| Feather Moss | Brachythecium spp* | xx | xx | |

| Pincushion Moss | Ulota crispa* | x | xx | |

| Bristle Moss | Orthotrichum spp* | x | xx | |

| LIVERWORT | New York Scalewort | Frullania eboracensis* | xxx | xx |

| Tree Ruffle Liverwort | Porella navicularis* | xx | xx | |

| Flat-Leaved Scalewort | Radula complanata* | xx | xx | |

*image available in article

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

One thought on “Two Old Beech Trees…”