Back in school, I learned that fungi play diverse and important roles in ecosystems, helping to break down organic matter and recycle nutrients, often through symbiotic relationships with plants and other organisms (e.g. lichens). Fungi act variously as decomposers and nutrient cyclers, as mutualists, and sometimes as pathogens.

.

Saprophytic Decomposers: Most fungi are saprophytic decomposers, breaking down dead plant and animal matter, returning essential nutrients to the soil. This process is crucial for nutrient cycling and supporting plant growth and all life. Most mushrooms we see in the forest and elsewhere are decomposers.

.

.

Mutualists: Some fungi are mutualists, forming symbiotic relationships with plants and animals, where both organisms benefit. For example, mycorrhizal fungi form a symbiotic relationship with plant roots, helping plants absorb water and nutrients, while the fungi receive carbohydrates from the plants. The underground symbiotic mycorrhizal network in the soil connects an ecosystem’s vegetation and helps transport nutrients and defense compounds from plant to plant.

.

.

Another example are the lichens, which are an association of fungi, algae and bacteria that work together to form a kind of community-organism, each putting in something for the group and ultimately the ecosystem. Lichens are more appropriately called a micro-ecosystem, an association of symbiotic organisms working together and living more successfully for the association. Lichen inhabit most substrates, from trees and the ground, to rocks and artificial surfaces, to tiny leaves, and even the air.

.

.

Parasitic Pathogen: Fungal pathogens are natural components of healthy forest ecosystems, playing a significant role in eliminating weak and unfit trees. These fungi feed on living hosts, and don’t necessarily kill them. An example is the cedar-apple rust caused by the parasitic fungus Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae. This fungus needs two hosts to complete its life cycle, living as a parasite on the largely unaffected juniper host, where it forms galls from which its spores hop onto a nearby apple tree to infect them.

.

.

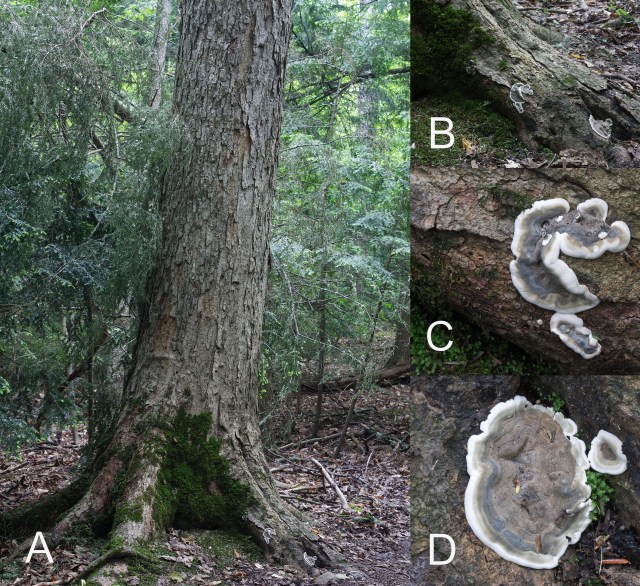

I also found Brittle Cinder Fungus (Kretzschmaria deusta) on the base of maple trees and fallen logs and stumps in the Mark S. Burnham Forest in Ontario. K. deusta colonizes trees through heart rot, invading the tree through injuries or root contact with infected trees, and spreads from the root base to the bole. It prefers broadleaved trees such as Oak, Beech, Horse chestnut, Elm, Sycamore, Hackberry, Tilia, and particularly Maple. Metro Vancouver Regional Parks determined that maple trees are not only particularly vulnerable to this fungus; diseased trees tend to belong to the large and very large diameter classes. In other words, veteran trees.

.

.

Brittle Cinder Fungus (Kretzschmaria deusta)

Kretzschmaria deusta is probably #1 on an arborist’s list of most concerning parasitic tree fungi, considered one of the most impactful root and butt decay pathogens of urban trees. K. deusta causes soft rot type II and has a broad host range. This pathogen has a heart rot mode of establishment and is known to cause breakage in seemingly healthy trees. This is because by the time its visible fruiting bodies show on the tree, this fungus has already done its work inside the tree, degrading the cellulose and hollowing out the plant cell walls, greatly diminishing the tree’s strength and making branches and trunk brittle and unsafe. Often the crown of the tree and its outer bark will show no symptoms of the infection; but inside, the tree is severely losing its strength. An infected tree may simply snap off completely at its base. No cure is known. Once the fungus establishes, shown by the appearance of the fruiting bodies, the tree will perish in a relatively short period of time, in as few as five years. Forest paleoecological studies have shown that climatic change can exacerbate K. deusta outbreaks.

.

.

This spring, I found Brittle Cinder Fungus (Kretzschmaria deusta)in the Mark S. Burnham mixed old-growth forest near Peterborough, ON. I observed grey with white-margined patches on the base of a very large veteran maple tree (Maple #5 in my maple study) and on rotting logs and stumps of maples and beeches. These somewhat concentric growths often had ‘rings’ of varying colour from tan-brown to bluish-grey. I’m told that this asexual phase is commonly seen in the late spring and produces conidia, not spores. Brittle Cinder Fungus spreads through wounds, root grafts or airborne spores. Its young asexual phase—the growth that first caught my eye—resembled a grey marshmallow that had touched a campfire, with white spongy margins and a soft velvety texture; larger patches often had a powdery dusty centre that rubbed off easily to expose a brownish bumpy surface and sometimes with embedded black dots.

.

.

Many patches also displayed the phenomenon of guttation, when drops of exudate pearl up on the fungus. I’m told that this results from active metabolic activity and the need to expel excess water and unwanted metabolic byproducts. Some of the guttated drops were a the colour of maple syrup. This asexual phase is commonly seen in the late spring and produces conidia, not spores.

.

.

As the fungus ages in the summer, it forms a sexual stage that is brown-black and resembles burnt bark or hardened molten lava. Once I was alerted by the asexual stage, I also noticed this stage in places. I found that it easily flaked away and to the pressure of my fingers, crumbled to dust. The word deusta means “burned up” in Latin and describes the blackened appearance of the sexual fruiting body of the fungus. This camouflaged stage is easily overlooked. The brown-black bumpy crust or ‘shell’ eventually cracks open, revealing a whitish powdery flesh or spore mass that disintegrates and releases spores to the wind or rain.

.

.

Hidden inside the tree, K. deusta causes a soft rot, breaking down cellulose and lignin and decaying the trunk and/or root of living trees. Once the tree is infected with Brittle Cinder Fungus, the wood tissue loses strength, the tree becomes unstable and may topple as the fungus digests the inside of the tree. Once the tree dies, this facultative parasite shifts its behaviour to behave as a saprophyte, acting like white rot, digesting the dead wood and returning nutrients back to the soil.

.

.

Shapeshifting Fungi

What I later learned is that many fungi are shapeshifters, shifting from one role to another depending on the changing conditions.

.

In a previous article, I talked about the endophytic fungus Coprinellus domesticus that inhabited a fallen black walnut tree in the forest near my house. When a tree is alive and healthy, endophytic fungi form a mutual relationship with it, providing protection from pathogens and sharing beneficial secondary metabolites. Endophytic fungi are universally present in every plant species. Rashmi, Kushveer and Sarma in Mycosphere report that “a single tropical leaf may harbour 90 endophytic species.” When the tree grows old and starts to die, the relationship changes. The relationship of the endophytic fungus with its host tree works on a continuum, potentially switching from mutualism to antagonism depending on environmental pressures; the endophyte becomes saprobic once the host starts dying, helping to decompose it and eventually returning nutrients back to the soil.

The parasitic Brittle Cinder Fungus Kretzschmaria deusta does something similarly shifty.

Kretzschmaria deusta can act as a pathogen, entering a live tree and eating away at the living tissue of the tree, then changing to a saprophytic decomposer when the tree dies, breaking down the dead materials and returning them in accessible form to the environment. Or it may act as a saprophytic decomposer, skipping the parasitic stage, by colonizing logs and stumps and decomposing and recycling nutrients in the ecosystem.

.

.

Jack Rogers and colleagues argue that because of K. deusta’s capacity to survive on dead material and because they seem to be parasites of opportunity rather than necessity the scientists considered them facultative parasites. I simply call them shapeshifters, adapting their behaviour and appearance to a changing environment.

Fungi interconnect all things on this planet. Helping others fully live; helping them efficiently die. Fungi literally stitch a living tapestry of balanced tension between symbiosis and antagonism, all orchestrated by the environment and climate–and completing a cycle that has marched on for millennia. And will likely continue for many more in the future.

.

References:

Barron, George. 2014. “Mushrooms of Ontario and Eastern Canada.” Partners Publishing, Edmonton, AB. 336pp.

Baroni, Timothy J. 2017. “Mushrooms of the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada.” Timber Press, Inc., Portland, Oregon. 598pp.

Cordin, Giorgio, et. al. 2021. “Kretzschmaria deusta, a limiting factor for survival and safety of veteran beech trees in Trentino (Alps, Northern Italy). iForest Biogeosciences and Forestry 14: 576-581.

Cannon, Sam. 2024. “Kretzschmaria deusta (aka brittle cinder) w/Sam Cannon @ The Treeist Morning Meetings”. YouTube video:

Gugielmo, Fabio, Serena Michelotti, Giovanni Nicolotti, and Paolo Ganthier. 2012. “Population structure analysis provides insights into the infection biology and invasion strategies of Kretzschmaria deusta in trees.” Fungal Ecology 5(6): 714-725.

Kuo, M. 2018. Kretzschmaria deusta. Retrieved from the MushroomExpert.Com Web site: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/kretzschmaria_deusta.html

Munteanu, Nina. 2018. “Do Plants Communicate? Why Is This Important For Us?” The Meaning of Water, September 9, 2018.

Rogers, Jack, D.,Wu-Ming Ju, Micheal J. Adams. 2011. “Kretzschmaria: Ecology and Host-Parasite Relationships.” Mycology. Sinica, edu. tw

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

2 thoughts on “Misunderstood Shapeshifting Fungi: Kretzschmaria deusta”