.

I had just moved back to British Columbia from Ontario and was looking for a forest to explore. There are many lush rainforests along the BC coast and I will be exploring all of them over time. This day, I chose to drive inland from Ladner to Campbell Valley Regional Park, where I’d been horseback riding years ago.

.

.

.

This time, I took the north entrance and dispensed with the horse to take the slow way—walking—to explore the fractal forest, both large and small. I started with the Little River Loop Trail, which took me through a lush forest (large Douglas firs, cedars, Bigleaf maples and vine maples with huckleberry and Oregon grape undergrowth) and twice crossed the winding Little Campbell River marshland along boardwalks.

.

.

I met several new ‘old’ friends along the trail. It helped that I was eating my peanut butter and jam sandwich as I strolled along the trail; the scent must have been so tantalizing! One bold chestnut-backed chickadee flew within inches of my nose in search of a scrap of food.

.

I hadn’t gotten very far, just to the forest verge on the edge of the marsh, when I noticed six large deciduous trees with fairly smooth, shallowly furrowed, bark. The largest and oldest tree showed some bark separation into irregular flat plates. The trunks were covered in moss and a plethora of mostly crustose lichen. I immediately thought of the two old beech trees covered in crustose lichen in the Mark S. Burnham Forest, Ontario, that I’d documented a while ago when I lived there. According to lichenologist Joe Walewski, an abundance of crustose lichen on a tree signifies maturity. While crustose lichen tend to be the first colonizers of rock, they are later colonizers of trees. So, these trees were quite mature.

.

.

But these couldn’t be beeches, I thought, despite the smooth bark and similar looking leaves—the beech tree isn’t normally found here. I thought briefly of a yellow or paper birch but the bark and the leaves also didn’t match. It took me a while to realize that these were my old friends from BC, the red alder (Alnus rubra). The deep veined leaves with scalloped edges matched; but it was the distinctive female catkins that I found on the ground that provided incontrovertible proof. Of course, it made sense that these trees flourished by the marsh—alders love water. And what better tree to feature on my return to British Columbia than this colourful and highly successful representative of my new home.

.

.

This scrappy, short-lived tree (grows to a maximum age of 75 years achieving a dbh of 60 cm and a height from 15-30 m) springs up quickly in disturbed places, growing rapidly and forming dense thickets of saplings in varied habitats—giving it the reputation of being a ‘weed tree.’ But the red alder is so much more…

.

Early Succession Pioneer Trees

.

In truth, the red alder serves an important role in succession as a pioneer (early sere) species, often the first colonizer of a disturbed area—from fire, logging, flooding or avalanches. Plant in Place calls them “the driving force of renewal in the forest,” and goes on to describe the alder’s place in both growth and destruction cycles inherent in all ecological succession.

Like moss, lichen and some fungi, alder trees thrive in places that have been burned or swept away, areas of disturbed mineral soils and often copious sunlight. Pioneer species play a key role in creating habitat for later sere species by building soil and providing shade for other plants to establish, ultimately increasing biodiversity in ecosystems. The red alder also forms a partnership with bacteria that fix nitrogen from the air through nodules that form on its shallow wide-spreading root system; these make nitrogen available for plant growth and allows the red alder to grow in poor soils that lack nitrogen. providing the ecological service of adding nitrogen to the soil. As the forest matures, the short-lived alder gives way to the shade of the slower growing tall conifers such as Douglas fir and cedar. Dead alders continue to provide habitat for wildlife and the nutrients released from the rotting wood become available to other fungi, animals and other plants.

.

Red Alder Habitat & Distribution

.

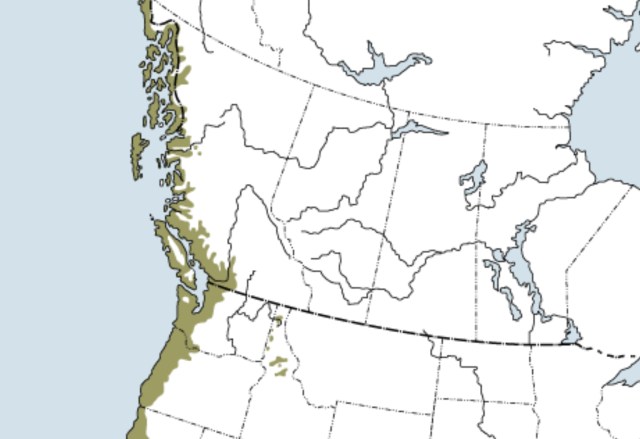

The red alder It is a costal tree and only appears within a narrow band within 150 km of the Pacific coast in Canada. Its preferred habitat is a floodplain and along streams. The red alder is naturally found in moist forests, around marshes and swamps, or along stream shorelines and ranges from southeast Alaska to southern California, from sea level up to about 2,500 feet elevation. It generally occurs within a hundred miles of the coast. It often forms pure stands, but also commonly mixes with black cottonwood, grand fir, Douglas-fir, western redcedar, western hemlock, western yew, bigleaf maple, and vine maple—all of which occur in Campbell Valley Park.

.

.

Red alders prefer sunny areas that aren’t too dry and where the seeds can germinate and grow fast. It does not tolerate very dry sites but can live in wet and soggy soil. According to The Natural Edge, Red Alder grows best in moist to wet conditions with full or partial sun exposure with pure alder stands often occurring along streambanks. It prefers sand or loam soils but can grow in a variety of soil types. It can tolerate poor soil, steep slopes, drought, and periodically flooded areas. Because of this, river banks are generally where the largest and oldest red alders occur. My alders were very well placed, on the forest verge with the marshland. Fairly sunny and wet.

.

Rapid growth allows the red alder to outcompete slower growing conifers around them (according to the USDA, seedlings can grow more than a metre per year during the first 20 years of growth with a 20-year old tree easily reaching over 20 metres high). The Government of Canada states that the maximum age of Red Alder is 75 years, achieving a dbh (diameter at breast height) of 60 cm. The USDA notes that mature alders [75 years old] on favourable sites can achieve a trunk width of 55-75 cm (dbh) and a height of 30 to 40 m.

.

The trunk diameters of the six red alders I looked at measured with smaller ones from 18 to 20 cm dbh and two larger trees from 35 to 51 cm dbh. Based on the literature, I estimated that these trees ranged with smaller ones from 19 to 26 years old and two larger ones from 36 to 55 years old. A good stand of mature alders.

.

Red Alder Life Cycle

.

The red alder is monoecious, bearing both female flowers and tassel-like male catkins. The male and female catkins emerge before the first leaves in spring (February), creating an orange-red haze around the bare branches of an alder stand. Yellowish male catkins dangle with tiny red flowers. Their pollen blows in the wind onto the less conspicuous green female catkins. As the female catkins mature and develop seeds in summer, they turn brown and resemble small pinecones. The tiny, winged seeds disperse in the wind and are spread by birds and other animals. Many are eaten by birds or mice, killed by drought, consumed by fungus, or just land in a bad spot.

.

Red Alder Human Uses & Mythology

.

The red alder is often used in restoration projects for its fast growth, soil stabilization and nitrogen fixing abilities. According to the USDA, Red alder is an excellent species for re-establishing woodlands. The trees are used in forested riparian buffers to help reduce stream bank erosion, protect water quality, and enhance aquatic environments. Plantings of red alder are effective in controlling erosion on steep slopes in disturbed areas (Uchytil 1989). These fastgrowing trees help to prevent soil erosion because of their dense canopy cover and thick litter layer that forms within the first 3 to 5 years. The leaf litter is high in nitrogen content (Labadie 1978).

Indigenous people use the wood of red alder to make canoes, tools, and cooking utensils. They use red alder bark to make dyes and medicines and weave its fibrous roots into baskets. Plant in Place provides more details on this tree’s many uses.

.

Alder Bark Ecosystem

The bark of red alder is relatively smooth and whitish-grey. But the bark is often obscured with a rich variegated carpet of moss and lichen—forming a diverse ecosystem worth investigating.

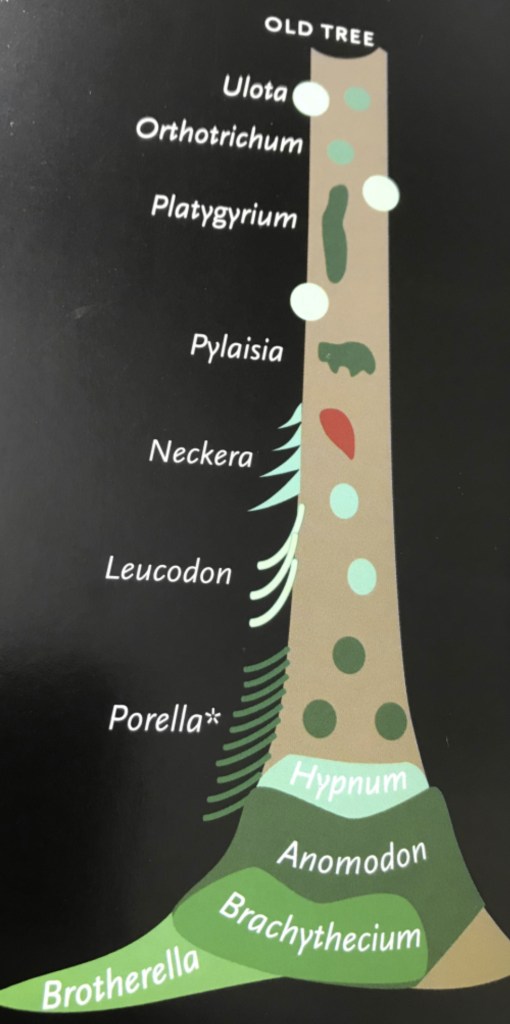

I noted a clear vertical stratification, with mosses and liverworts concentrated at the tree base and some lichens more obvious as one moved up the tree or on upper branches.

Jerry Jenkins’s excellent moss guide for old trees in northern forests showcases the vertical colonization by the most common mosses and liverworts growing from the base ‘skirt’ up the height of the tree. My observations closely matched his list and graphic portrayal of moss colonization of an older tree.

*Porella is the Tree Ruffle Liverwort; all others are mosses

Vertical stratification of common mosses on an old tree (image from Jenkins, 2020)

.

Mosses

.

I identified several mosses that colonized the red alder’s trunk. As with many other trees, mosses were most abundant at the base of my alder trees. Mosses I identified included Feather Moss (Brachythecium spp.) and Oregon Beaked Moss (Eurhynchium oreganum) with its small fern-like leaves, known to commonly occur on red alder trees. I also found cat-tail Moss (Isothecium stoloniferum)–abundant in the park–on most of the alders.

.

.

The most dominant moss, from the tree base up the tree was Cat-tail Moss (Isothecium stoloniferum) with their ‘tails’ swinging down in waves. I also noticed Tree Ruffle Liverwort, Porella navicularis (an old friend I’d seen growing at the base of several old sugar maple trees in Ontario), growing among the Cat-tail moss.

.

.

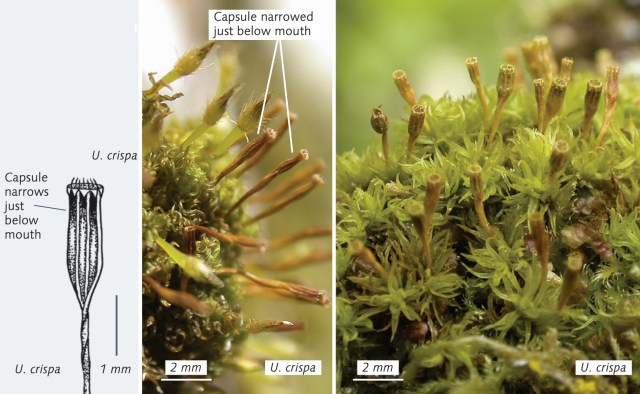

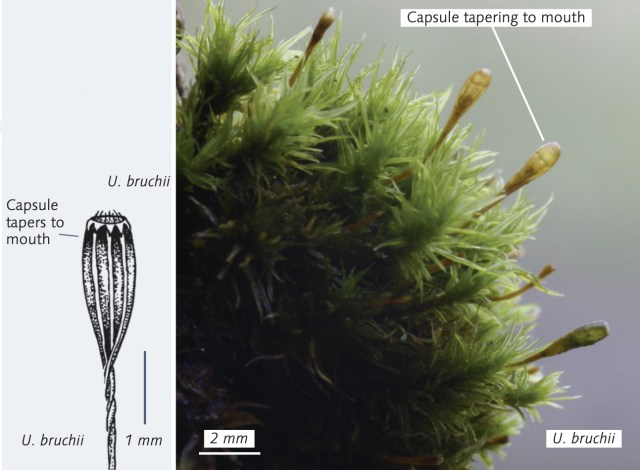

Farther up the tree, I found patches of Dusty Fork Moss (Dicranum fuscescens) and Crisped/Bruch’s Pincushion Moss (Ulota bruchii / Ulota crispa).

.

.

Both Ulota mosses are very similar in looks and habitat. Leaves are spearhad-shaped with both becoming somewhat crisped when dry. A key difference lies in the shape of mature capsules, with U. crispa capsules being wide-mouthed and narrow immediately below the mouth, whereas those of U. bruchii taper to a narrow mouth. Even this is not a clear differentiation, given overlap and variation. The British Bryological Society clearly shows the key diagnostic features.

.

.

.

.

.

I’m also told that the licorice fern (Polypodium glycyrrhiza) tends to colonize red alders, though I did not find any on the alders I investigated. I did spot them on some Bigleaf maples along the trail.

.

Lichens

These large old red alders were literally covered in corticolous lichen. Most lichen were crustose—suggesting mature trees—but I also found several fruticose and foliose lichen.

.

.

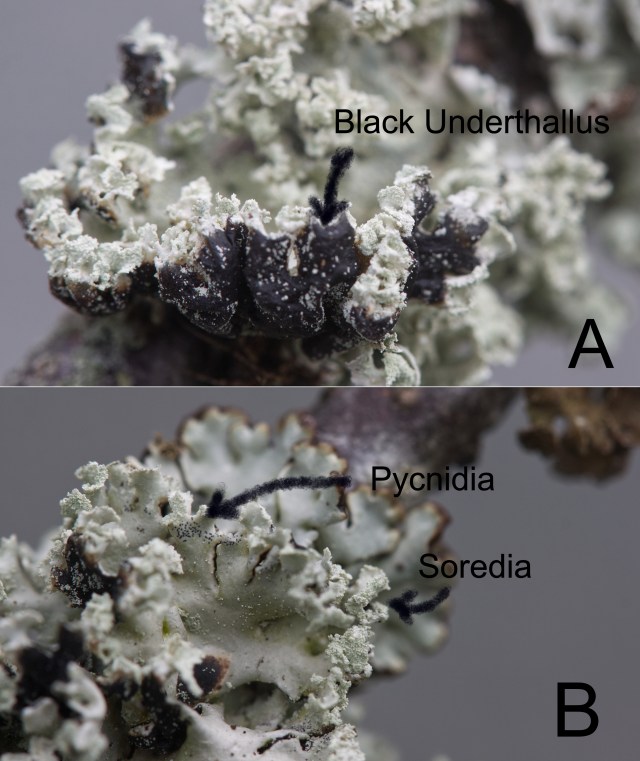

Tree Flute Lichen (Menegazzia subsimilis)* is a common foliose macrolichen in the Parmeliaceae and fairly common throughout the world, often found on rocks and trees, and frequently on red alders in British Columbia. It is also called honeycombed lichen (due to its distinguishing feature of having holes. I originally identified it as Monk’s Hood Lichen (Hypogymnia physodes) a common lichen in boreal and temperate forests of the northern hemisphere, which also inhabits red alders. Both resemble one another greatly, sharing commonalities in a thallus that when dry is grey to yellowish-green and loosely attached to its substrate; and when wet the thallus turns deep sea-green as the algal partner actively photosynthesizes. Both have hollow lobes, often brownish toward their margins that are often turned up and covered in white powdery soredia. The lower part of the thallus is black and the lichen has abundant tiny black pycnidia that resemble pepper granules on the upper thallus towards the tips. What differentiates these two is the presence of holes on the upper surface of the thallus of Menegazzia subsimilis, a diagnostic feature easily recognized once identified.

*This identification was made thanks to a suggestion made by “MagnificentSweetly” (see comments section below), which I confirmed through the literature.

.

.

.

Hammer Shield Lichen (Parmelia sulcata) is a foliose lichen whose thallus is dimpled with depressions and lower surface is black with unbranched rhizines. The Hammer Shield Lichen is fairly common in north temperate forests, typically inhabiting the bark of deciduous and coniferous trees as well as fence posts. They are the first organisms to colonize trees (and even picnic tables!). Ruby-throated hummingbirds are known to camouflage their nests with bits of Parmelia.

.

Common Powderhorn (Cladonia coniocraea) is a fruticose lichen that is rather ubiquitous, prefering moist and shady habitats of several different substrates. I’ve seen it on an old wooden fence post, on the shallow ground covering a granite outcrop, and on an old cedar stump and the tree bark of both deciduous and coniferous trees. It’s known to tolerate air pollution and appears to thrive in urban areas.

Close up of Cladonia coniocraea lichen on red alder (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

.

.

Bristly Beard Lichen (Usnea hirta) and Oakmoss (Everna prunastri), both fruticose lichen, were found farther up the tree and on its branches. Usnea forms densely long-branched tufts and is considered pollution sensitive. Usually found high in the crown of trees, its branching form is suggested to reduce drag from the wind. Others suggest that branching has more to do with capturing light and carbon dioxide. Oakmoss, a branched lichen that resembles deer antlers, prefers oak bark to grow on, but grows on other deciduous and coniferous trees. This lichen relies on the air, rain and airborne debris to get its nutrients; it is sensitive to certain air pollutants.

Usnea hirta on a red alder twig (photo by Nina Munteanu)

.

.

Bitter Wart Lichen (Lepra amara) is a crustose corticolous lichen I’d seen on old logs and maple and poplar trees in Ontario. I noted its pale greenish-grey thallus (green from its photobiont partner Trebouxia, a green alga) and warts of yellow-green punctiform soralia on my alders. This lichen is commonly found on deciduous trees and gets its name from the strong persistent bitter aspirin taste of secondary metabolite picrolichenic acid. This lichen enjoys the smooth, less-acidic, and moist, well-lit environment of red alder bark.

.

.

.

Bark Barnacle Lichen (Thelotrema lepadinum) is a crustose corticolous lichen often reported on red alder bark, that forms creamy grey-white crusts on the surface of tree bark. The apothecia of this crater lichen genuinely resembles barnacles, with a thick outer rim and thin papery inner rim. Italic 8.0 describes the apothecia as “conical thaline warts” with a “crater-like summit, the rim usually incurved, with a whitish membrane at the bottom which disrupts at maturity, leaving small, white fragments in the centre of the blackish apothecial disk.” Its genus name—Thelotrema—is from the Greek words meaning “perforated nipple.”

.

.

Barnacle Lichen is frequently found on bark of red alder and both thrive in humid, oceanic environments of the Pacific Northwest. Cumbria Woodlands indicates that Barnacle Lichen’s preference for red alder is partly because it prefers smooth bark. Italic 8.0 notes that, in Europe, Barnacle Lichen is often found on the smooth bark of beech and acidic bark of fir. Red alder bark is both: smooth and mildly acidic. Woodland Trust writes that this lichen is “found mainly on the bark of living trees in ancient woods, and it is indicative of longstanding woodland conditions.” Atlas of Czech Lichens notes that this lichen usually grows on smooth acidic bark of older deciduous trees and is a bio-indicator of old-growth forests.

.

.

Smooth Saucer Lichen (Ochrolechia laevigata), also called Crabseye Lichen and Glazed Donut Lichen, is a crustose lichen often found on red alder bark in the Pacific Northwest. The lichen typically has a smooth, white to greyish thallus with distinctive ‘pimples’ of the spore-producing apothecia scattered throughout its surface. The apothecia are saucer-shaped disks of yellow-brown to orange rimmed by lighter margins. This lichen seems to prefer alder, but can also be found on vine maple and some other deciduous trees.

.

Rim Lichen (Lecanora pacifica): On another visit to this forest, I found a green version of this saucer lichen and wondered if the Smooth Saucer Lichen varied in its disk colour that much; I couldn’t find any reference to this. Then after more investigation, I determined that this was in fact a species of Rim Lichen (Lecanora pacifica) with very similar morphology and habitat preference (deciduous trees including red alder) and whose slightly pruinose disk varies in colour and hue from yellow to olive-brown to green-grey.

.

.

.

Common Script Lichens (Graphis scripta) are a crustose lichen with grey-green powdery thallus and found abundant on the large old alders I investigated. The script lichen is characterized by and gets its name from the darkish strange raised squiggles that resemble short scribbles that look like a secret alphabet on the thallus. the dark squiggles are actually elongated and narrow spore-producing apothecia. The lichens start rather inconspicuously as grey smears on a tree; eventually the grey thallus develops visible squiggles of apothecia that look like a pair of lips, called lirellae. The script lichen prefers the smooth bark of the alder tree or young maple or poplar on which to ‘write’ its story.

.

.

Orange Rock Hair (Trentepohlia sp.) is a green alga often serving as the photobiont of lichens, but also often occurring as an independent subaerial alga that obtains its nutrients form humidity, rain and sunlight. This green alga commonly grows on alder trees, forming felt-like orange patches on the smooth alder bark. The orange colour comes from carotenoid pigments that mask its green chlorophyll. I previously documented the Red Bark Phenomenon caused by this dynamic green alga when I discovered it on several poplar and hemlock trees in some Ontario forests with the article, “When Green Algae Turn Red: The Red Bark Phenomenon.”

.

References

Cheah C. and Li D.W. (n.d.). “The Red Bark Phenomenon.” CAES. The Red Bark Phenomenon (ct.gov)

Cheah, Carole. 2016. “The Red Bark Phenomenon.” (PDF) The Red Bark Phenomenon (researchgate.net)

Government of Canada. “Red Alder”. Website, last modified 2024-11-12.

Jenkins, Jerry. 2020. “Mosses of the Northern Forest: A Photographic Guide.” Comstock Publishing Associates, Cornell University Press, Ithaca. 169pp.

McCume, Bruce and Linda Geiser. 2023. “Macrolichens of the Pacific Northwest” 3rd edition. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis. 549pp.

Sanders W.B. & Masumoto H. 2021. “Lichen algae: the photosynthetic partners in lichen symbioses.” The Lichenologist 53: 347–393.

Uchytil, R.J. 1989. “Alnus rubra”. In: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory 2001, May. Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ . 2002].

USDA. “Silvics of North America: Red Alder” USDA Forest Service. Website

Walewski, Joe. 2007. “Lichens of the North Woods.” Kollath & Stensaas Publishing, Duluth, MN.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

Menegazzia subsimilis rather than Hypogymnia physodes.

“This distinctive genus is likely to be confused only with Hypogymnia. Both have hollow lobes…” – McCune and Geiser (2023) Macrolichens of the Pacific Northwest (superb book)

Agree – red alder is important, and great for lichens!

(I don’t know why WordPress calls me magnificentsweetly… I have found it difficult to comment on WordPress.)

LikeLike

Thanks for your suggestion. Much appreciated! I went back to the literature and found that the macrolichen is indeed the Tree Flute Lichen (Menegazzia subsimilis) and not Monk’s Hood Lichen (Hypogymnia physodes), given that it has perforations (holes) in its upper thallus, which Hypogymnia physodes does not have. Many thanks! These two lichen are indeed very similar! They even share the red alder tree as a similar habitat (substrate).

LikeLike