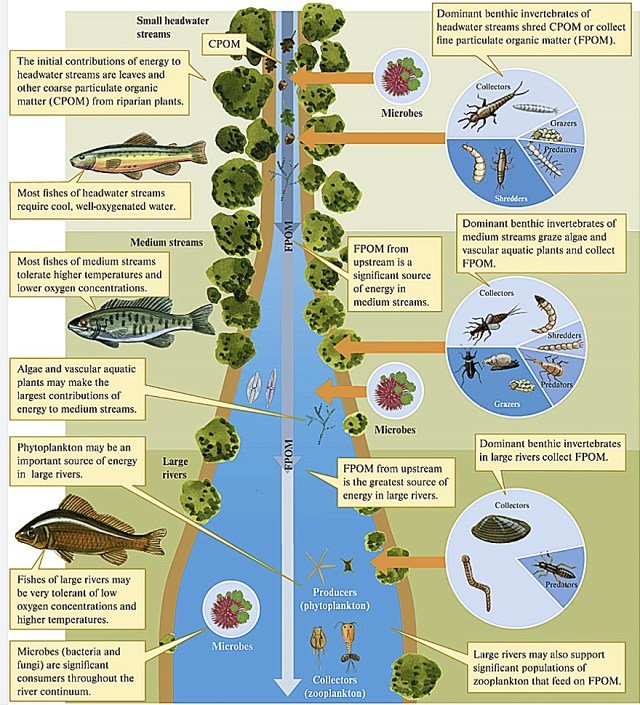

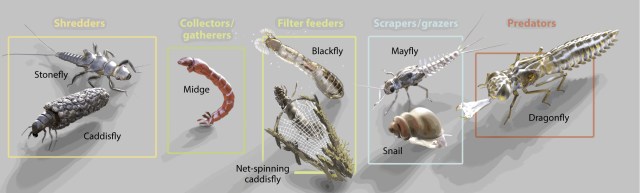

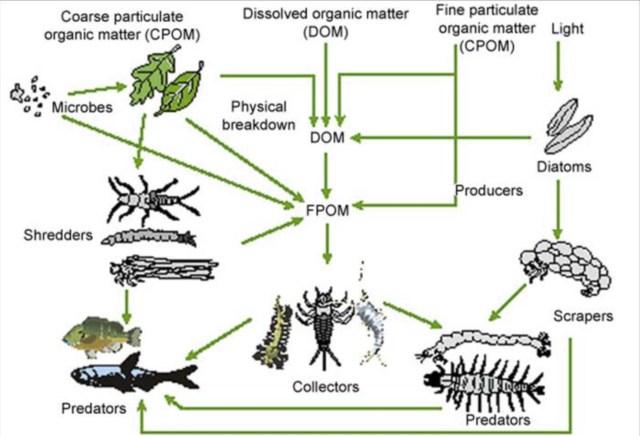

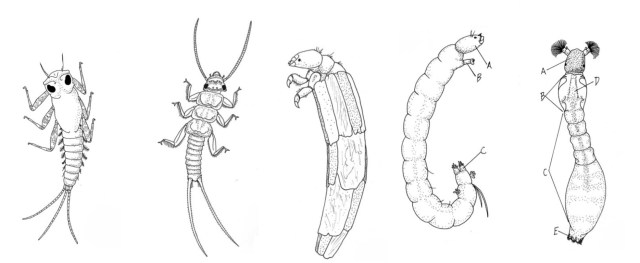

I’m a limnologist and aquatic ecologist. I spent several years of field work walking along streams, studying how energy and nutrients flow through them, what determines what lives in them and why. I studied the River Continuum Concept (RCC), which explains how rivers change from their rushing headwaters to their gliding mouths, and predicts a gradient of physical conditions that shape distinct biological communities and energy use that shift downstream from shredders to collectors and grazers and finally to filter feeders. For instance, headwater organisms such as shredders (e.g. stoneflies, amphipods) rely mostly on terrestrial inputs (allochthonous) such as leaves for nutrients and energy; downstream communities of large rivers (e.g. grazers such as snails and collectors such as filter feeding black larvae) use mostly internal sources (autochthous) sources or organic matter including periphyton and phytoplankton to survive.

.

.

Jason G. Freund at The Scientific Fly Angler provides a good summary of the River Continuum Concept. For more science on the science of the RCC, check out this 2020 article by Doretto et al. in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences.

.

River Continuum Concept & Benthic Macroinvertebrates

.

To briefly summarize the concept, let’s start with the headwaters of a mountain stream as it flows downstream and gets larger, capturing water and energy in the form of organic matter from a larger watershed. Organic matter that enters the stream is decomposed, consumed and transformed (via poop) or transported downstream. As the volume of water (discharge) increases downstream, both width and depth increase. Substrate, in turn, decreases from large boulders and rocks to silt, sand and organic matter. The organic matter also decreases in size forming smaller particles as they move downstream. Temperature also increases downstream as oxygen decreases downstream. The proportion of benthic macroinvertebrate functional feeding groups—shredders, collectors, grazers, and predators—shift downstream with the type and source of energy available to them.

.

.

A great diversity of feeding strategy often occurs within the same group. For instance, the mayflies or Ephemeroptera are represented by shredders (e.g., Edmulmeatus grandis) that rip and chew large organic matter such as leaf litter and woody debris; other Mayfly species may act as scrapers or grazers for periphyton (attached algae) on rocks (e.g. most Baetidae and Heptageniidae); yet others act as collectors-gatherers or collectors-filterers of fine organic particles or detritus (e.g., Ephemeridae). Some mayflies are predators, stalking other invertebrates (e.g. Pseudiron centralis).

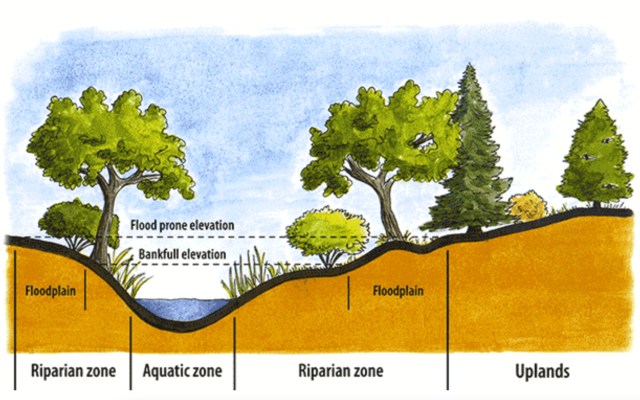

Small headwater streams are heavily influenced by the riparian zone (terrestrial area adjacent to the stream). Not only does this cover provide shade, which cools the stream; it also provides the chief form of energy as allochthonous energy through leaf fall—referred to as coarse particulate organic matter (CPOM). This CPOM, in turn, feeds the fungi, algae and macroinvertebrates (shredders and scrapers such as stoneflies, mayflies and some caddisflies) in the stream; these break down the leaves into smaller pieces as they decompose and are consumed. The broken down CPOM becomes FPOM (you guessed it; fine particulate organic matter), which is captured by collector macroinvertebrates such as net-spinning caddisflies. As it moves downstream, the organic matter continues to break down until it finally moves from particulate organic matter (POM) to dissolved organic matter (DOM).

.

.

As a stream grows in size, the riparian zone exerts less influence, providing less complete cover and allowing more sunlight to penetrate. The sunlight enhances authochthonous (in-stream) growth of algae and macrophytes. Production increases along with increased temperature and sunlight and shifts from relying on outside sources to inside sources of energy and nutrition.

.

When a Leaf Falls in a Stream…

.

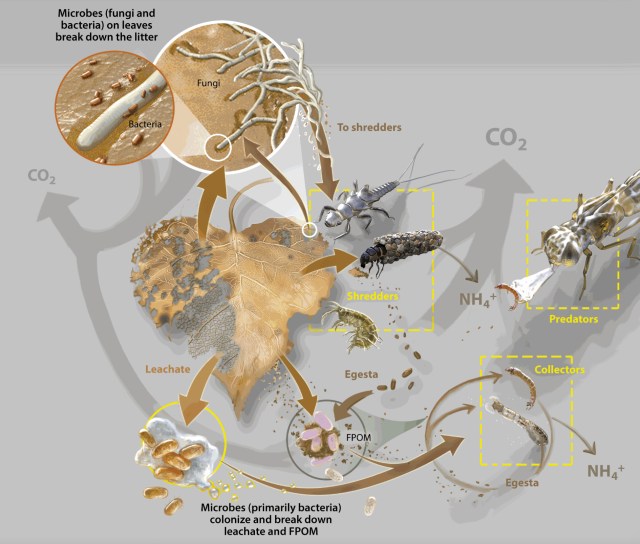

According to leaf litter biologist Jane Marks, biologist at Northern Arizona University, dead leaves provide a primary food base for life up the food chain, from fungi and bacteria that initially colonize the leaves, and the insects that chew them, up to the birds and fish that eat the insects. This creates a “brown” food web more expansive than the “green” food web the leaves nourish when they are still alive, writes Marks. Check out RAMP for a good summary of a food web, which includes descriptions of trophic levels—an organism’s position in the food web according to the number of energy-transfer steps required to reach that level—and trophic cascades.

.

.

A fallen leaf is broken down by fungi, bacteria and invertebrates (e.g. insects) that shred and consume leaf material. The insect waste, in turn, is eaten by other insects, birds and, if in water, fish. The leaf’s carbon and nitrogen is assimilated and released at various stages in the process. Fungi make the leaf easier for the bacteria to break down the leaf materials and prepare for insect consumption.

.

.

Leaves and branches that fall into streams from riparian trees and shrubs dominate that stream’s carbon budget. Litter breaks down through four main processes: leaching, mineralization by microbes, macroinvertebrate consumption, and fragmentation. Primary breakdown products carried out by bacteria, fungi, meiofauna, and invertebrates include leachate (dissolved organic compounds (DOM); think ‘tea’), fine particulate organic matter (FPOM), and inorganic matter.

.

.

While algae pump carbon into the stream ecosystem via photosynthesis, annual respiration by freshwater microorganisms tends to exceed photosynthesis, contributing to carbon release. However, Wallace and colleagues tell us that a small but vital flux fuels a macroscopic food web: from detrivores and predatory invertebrates to fish, amphibians and mammals in the riparian habitat—all playing a role in the fate of that leaf and its various components such as carbon. Ultimately, “alternative pathways to different fates are shaped by traits and interactions of leaves, microbes, and macroinvertebrates, all sensitive to a changing environment.”

Marks observes that organisms prefer different types of leaves. Rates of element loss from leaf litter and the pathways they follow also varies with leaf type. This makes sense, considering the leaves differing biochemical, physical and ecological traits. Marks argued that “refractory carbohydrates (lignin, tannin, and phenol) slow decomposition, whereas decomposition speeds up with increased labile carbohydrates (sugars) as well as macronutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus), micronutrients (calcium and magnesium), and specific leaf area, an inverse measure of leaf toughness. Litter toughness reduces decomposition and is postulated to be one factor explaining the paucity of shredders in tropical rivers.”

.

.

Importance of the Riparian Habitat, Biodiversity & Climate Change

.

Riparian areas (terrestrial habitats next to streams and rivers) are key habitats for ecosystem functionality; they help in water quality, hydrological balance, erosion control, thermal regulation and nutrient recycling—such as carbon sequestration. Riparian habitats are essentially transition zones, ecotones, which combine aspects of two ecosystems—aquatic and terrestrial; this makes them key to overall ecological health. The high biodiversity of riparian habitats fuel the ecosystems beyond them, ensuring that carbon sequestration occurs more than carbon release. These key habitats are currently being degraded through river channelization, dewatering, diversions, dam building, deforestation (often through development), and invasions of non-native species. Such degradation impacts wildlife habitat, increases temperature, reduces water quality and depletes river food webs of leaves. Changes in the riparian habitat, along with climate change, may also impact the types of aquatic organisms living in streams. Marks reports that species composition of riparian habitats is changing, with increases in drought-tolerant plants, agricultural species and non-native species—all potentially impacting litter content (and its decaying rate) and the freshwater organisms feeding on those leaves.

.

.

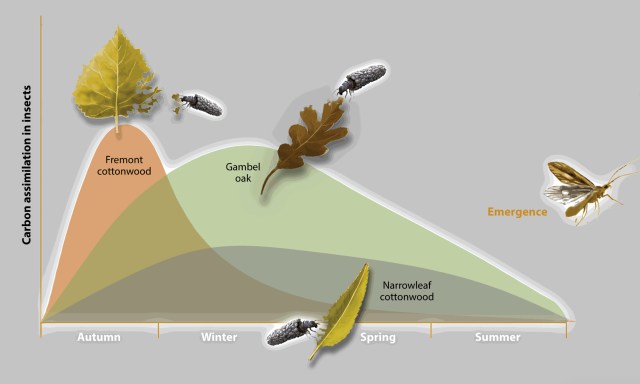

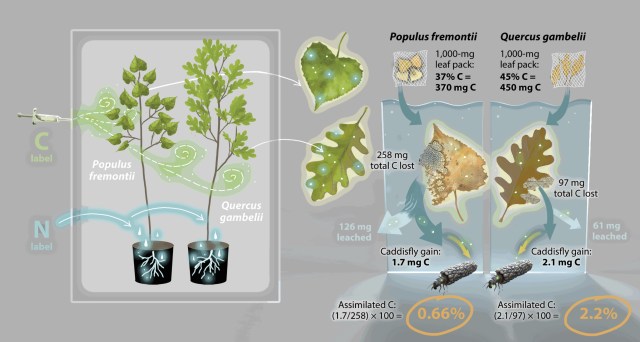

Grubbs & Cummins showed that leaves that decompose at different rates provide a continuum of resources for shredders throughout their life cycles. Isotope studies by Siders et al. showed that rapidly decomposing litter, such as leaves of Fremont cottonwood, provides a rapid but brief pulse of carbon and nitrogen to invertebrates shortly after leaf fall; in contrast, slowly decomposing litter (e.g. oak leaves) provides a more sustained flux and nourishment for macroinvertebrates in streams, and transferring more carbon up the food chain.

.

.

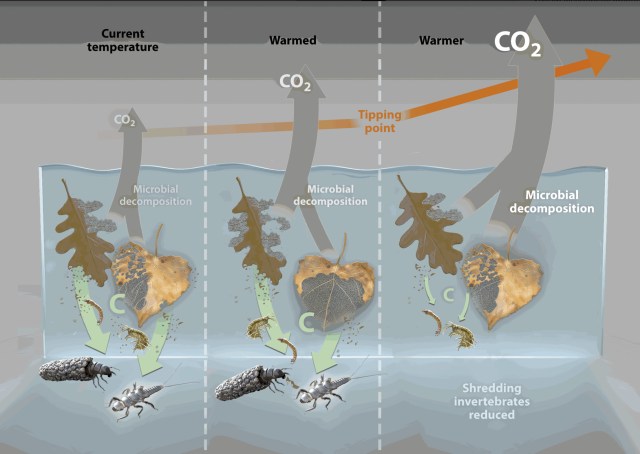

The reduction in trophic complexity due to global warming may shift the balance between macroinvertebrate vs microbe pathways of decomposition, favouring microbial processing. Marks argues that climate warming will cause invertebrate species decline, reducing the diverse response to litter breakdown, and more organic matter will be processed by microbes, increasing carbon export out of streams as carbon dioxide. In hypereutrophic streams, often associated with agricultural and industrial pollution, macroinvertebrates will be excluded by the loss of oxygen that accompanies these, while bacteria may still thrive. As temperature rises, decomposition rates initially rise and promote growth of decomposers and grazers; with increased temperature a tipping point is reached in which macroinvertebrates are excluded and microbial decomposition promoted through collateral effects (e.g. loss of oxygen and changes in nutrient limitation).

.

.

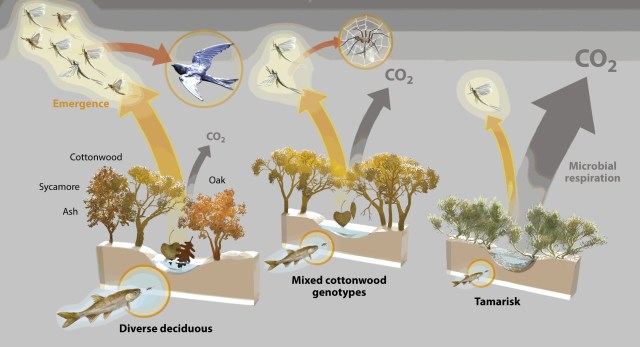

Global warming may promote monopolization of rapidly decomposing litter (e.g. tamarisk) over a diversity of slower decomposers (e.g. diversity of cottonwood, willow, oak, ash and sycamore) will decrease invertebrates and fish with implications to the bird population and others elements of a functional ecosystem.

.

.

.

References:

Begon, M., J.L. Harper, and C.R. Townsend. 1990. Ecology: Individuals, Populations and Communities. Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford.

Brunning, Andy. 2014. “The Chemicals Behind the Colours of Autumn Leaves.” Compound Interest, September 11, 2014.

Clements, F.E. 1905. “Research methods in Ecology.” University Publishing Company, Lincoln, NE. 368 pp.

Culp, J.M. and R.W. Davies. 1982. “Analysis of longitudinal zonation and the river continuum concept in the Oldman-South Saskatchewan River system.” Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 39(9): 1258-1266.

Cummins, K.W. 1973. “Trophic relations of aquatic insects.” Annu. Rev. Entomol. 18(1): 183-206.

Cummins, K.W. 1974. “Structure and function of stream ecosystems.” BioScience 24!11): 631-641.

Cummins, K.W. and M.J. Klug. 1979. “Feeding ecology of stream invertebrates.” Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 10:147-172.

Doretto, Alberto, Elena Piano, and Courtney E. Larson. 2020. “The River Continuum Concept: lessons from the past and perspectives for the future.: Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 77(11): . 2020.

Grubbs, SA and KW Cummins. 1994. “Processing and macroinvertebrate colonization of black cherry (Prunus serotine) leaves in two streams differing in summer biota, thermal regime and riparian vegetation.” Am. Midland Nat. 132:284-93.

Kaushik, NK and HBN Hynes. 1971. “The fate of dead leaves that fall into streams.” Arch. Hycrobiol. 68: 465-515.

Margalef, R. 1960. “Ideas for a synthetic approach to the ecology of running waters.” Int. Rev. Gesamtem Hydrobiol. Hydrogr. 45(1): 133-153.

Marcarelli, et.al. 2011. “Quantity and quality: unifying food web and ecosystem perspectives on the role of resource subsidies in freshwaters.” Ecology 92: 61215-25.

Marks, Jane. 2019. “Revisiting the Fates of Dead Leaves That Fall into Streams.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 50: 547-568.

Minshall, G.W., K.W. Cummins, R.C. Peterson, C.E. Cushing, D.A. Bruns, J.R. Sedell, and R.L. Vannote. 1985. “Developments in stream ecosystem theory.” Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 42(5): 1045-1055.

Munteanu, N. & R. Maly. 1981. “The effect of current on the distribution of diatoms settling on submerged glass slides. Hydrobiologia 78: 273-282.

Munteanu, Nina. 2016. “Water Is…The Meaning of Water.” Pixl Press, Delta, BC. 584 pp.

Poppick, Laura. 2020. “The life that springs from dead leaves in streams.” Knowable Magazine, 08.06.2020.

Reid, George K. 1961. “Ecology of Inland Water and Estuaries.” D Van Nostrand Company Inc. 390 pp.

Siders et al. 2018. “Litter identity affects assimilation of carbon and nitrogen by a shredding caddisfly.” Ecosphere 9.

Vannote, R. L., G.W. Minshall, K.W. Cummins, J.R. Sedell, and C.E. Cushing. 1980. “The River Continuum Concept.” Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 37(1): 130-137.

Wallace et al. 2015. “Stream invertebrate productivity linked to forest subsidies: 37 stream-years of reference and experimental data.” Ecology 96: 51213-28.

.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. For the lates on her books, visit www.ninamunteanu.ca. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press (Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

.