When you tug on a single thing in nature, you find it attached to the entire universe.”

John Muir

When I was in university, I entered grad school with the intention of studying lichen. I found these multi-species organisms fascinating. As with another love of mine—water—these organisms could be found everywhere and yet remained mysterious and little understood, or appreciated (just like water). Lichen are ubiquitous; occurring nearly everywhere from the most mundane to the most exotic habitats. Lichen lives in your backyard, on the ground, pavement, rocks, tree bark and branches, rotting logs, leaves and moss.

“A single Sugar Maple may be home to as many as twenty lichen species,” writes Joe Walewski, author of the guide book Lichens of the North Woods (Kollath & Stensaas Publishing, 2007).

But the professor I would have studied under had decided to retire and put me onto another professor who was researching zooplankton ecology. I ended up researching the dynamics of periphyton (attached algae) in streams (also very fascinating!). I wrote some papers on the effects of current on the colonizing strategies of periphyton communities on new surfaces. Oddly enough, as I look at it now, I see several similarities between periphyton and lichen that are also primary colonizers (of rocks and other surfaces) and are best described as mini-ecosystems.

My fascination for lichen never abated, despite (or was it because of?) what little I knew about them. I didn’t know that in the 1700s Carl Linnaeus, founder of taxonomy, called lichens “poor trash of vegetation.” I didn’t know that Linnaeus assigned just one genus to this huge family of organisms.

Thanks to the study of this “trash vegetation” this one genus—Lichen—has since expanded to encompass hundreds of genera and over 14,000 species of lichens. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds use Shield Lichen (Parmedia) in nest construction for camouflage; Warblers weave strands of draping Beard Lichens (Usnea) in their nests; White-tailed deer and flying squirrels eat lichens as do a myriad of tiny insects and slugs. Lichen are a staple for caribou who eat an average of three kilograms daily. According to Lazarus Sittichinli of the Gwich’in of the Northwest Territories, lichen takes a long time to grow; if you eat animals that eat willow, like moose, you will get hungry more quickly than eating animals that eat lichen, like caribou. Reindeer lichen (white moss or uudeezhu’ in Gwich’in) can be boiled to make a tea; Mary Kendi of Fort McPherson and Elizabeth Greenland agreed that it was good for stomach and chest pains.

Lichens are early succession primary sere colonists of rocks, trees, and soil, preparing them for mosses, grasses and ultimately trees.

.

.

Because lichens efficiently collect airborne substances, they help recycle chemicals in the air into the soil. Because of this, lichen can be used as bio-indicators to gauge air quality and act as sentinels of air contamination. Poor lichen diversity and abundance may signal instances of air pollution.

.

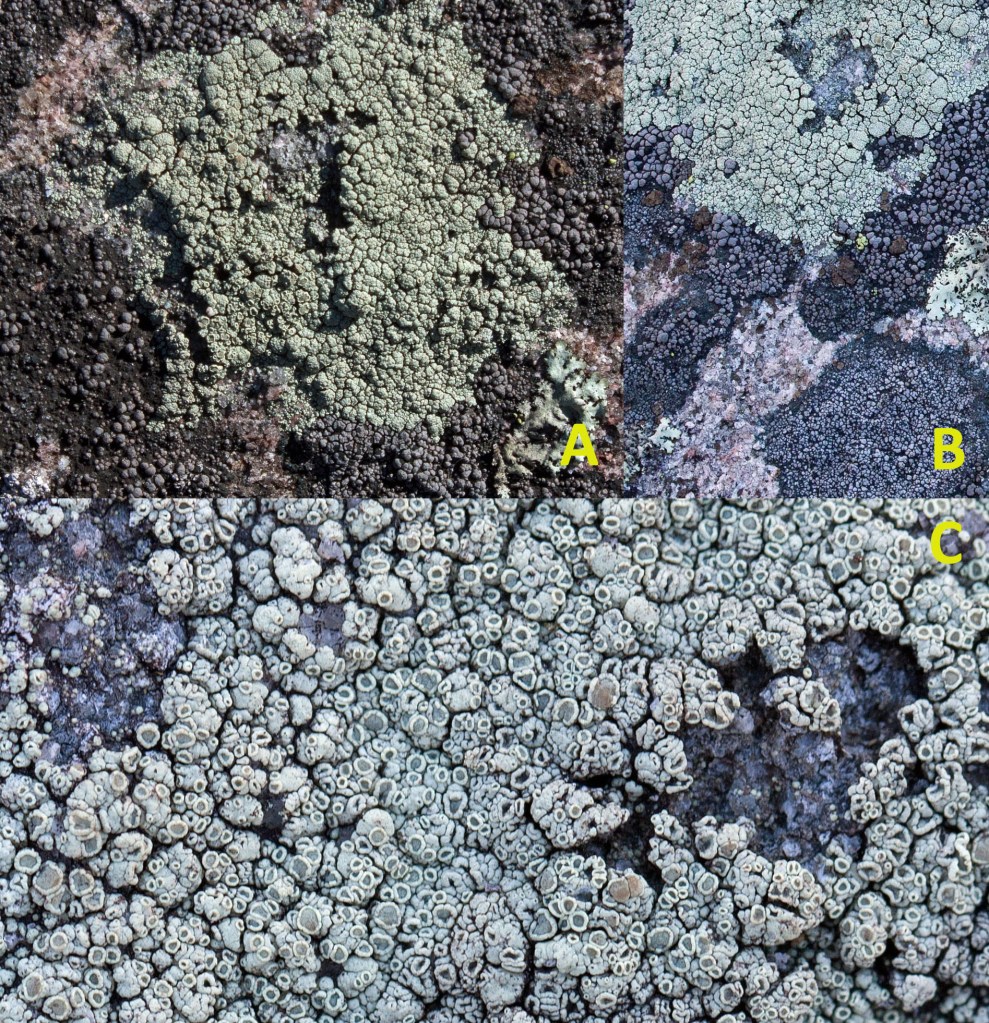

Lichens come in three major types or forms: fruticose, crustose, and foliose. Fruticose lichen form bushy growths, sometimes with erect branches or tufted and draping. Fruticose lichen are distinguished by often having stalks (podetia) common in the Pixie Cups (Cladonia). Crustose lichen often look like spray paint, with medulla (lower surface) directly adhering to the substrate and blending in (e.g. Lepraria or Phlyctis). Foliose lichen resemble leafy growths, divided by lobes that may end in apothecia (the fungal sexual apparatus) and with lower surface often differently coloured than the top surface. Typically, rhizines anchor this lichen to the surface (e.g. pelt lichen).

.

.

Types of Lichen Habitat

The lichen is all about relationship—with itself (between its fungus and alga self)—but also with the substrate, whether living or not, on which it colonizes. Important features of the substrate to the lichen include its texture, moisture retention, and chemistry. The three main types of substrate include ground, rock, and trees.

Ground Substrates (Terricolous Lichen)

The ground includes soil, sand, mosses and decomposing logs. The hyphae produced by terricolous lichen help stabilize and fertilize the soil with organic matter and nitrogen. Lichen that are light-coloured help keep the soil cool by reflecting heat. They also trap dust and act as substrates for other living things.

Rock Substrates (Saxicolous Lichen)

These include cliffs, talus, pebbles and boulders, as well as concrete and shingles and other artificial substrates. These saxicolous lichen are often found among the mosses that also colonize these same surfaces. Lichens grow among the rock crystals, helping to break down surfaces for mosses and other colonizers.

Tree Substrates (Lignicolous and Corticolous Lichen)

Lichen that grow on conifers and deciduous trees (lignicolous on wood and corticolous on bark), differ based on their surface textures, chemistry, light and moisture. Conifer bark, for instance, is rich in organic resins and gums, and is acidic. The canopy of a conifer is also more dense than most deciduous trees; this prevents some light from penetrating to the trunk. The sloping nature of spruce and fir trees also allows rain to fall to the forest floor rather than run down the trunk as it readily does on a deciduous tree. Anyone caught in a rainstorm, like me, will vouch for this difference.

As trees age, so does their bark. The bark of a sugar maple, for instance, is smooth when the tree is young; with age it softens, cracks and forms furrows that ooze alkaline nitrogenous compounds. Walewski tells us that older trees have a greater diversity of lichens. “Elm and poplar bark are low in acidity, stable and fairly absorbent. Oak, hickory and linden have hard, rough, acidic bark and host different [lichen]. Beech and other trees with smooth, living, green bark are home to yet another community of lichens.”

Two other habitats for lichen colonization and growth include leaves or needles (Foliicolous Lichen) and other lichen (Lichenicolous Lichen).

.

The Symbiotic Relationship of Lichen

As a writer, I see lichens as a cooperative character; a tight pair of characters, really. Lichens are a complex symbiotic association of two or more fungi and algae (some also partner up with a yeast and bacteria). The algae in lichens (called phycobiont or photobiont) photosynthesize and the fungus (mycobiont) provides protection for the photobiont. The fungus is commonly a member of the Ascomycetes, which include cup fungi, lobster fungi and morels. The most common algal partner is the unicellular alga Trebouxia and filamentous alga Tentepohlia. Sometimes a blue-green (Nostoc).

.

.

Walewski suggests that a lichen is not so much an organism as a lifestyle. They are “Nature in miniature.” And highly successful, given that lichen have populated the entire planet. Eight to ten percent of terrestrial ecosystems are thought to be dominated by lichen.

Both the algae and fungus absorb water, minerals, and pollutants from the air, through rain and dust. In sexual reproduction, the mycobiont produces fruiting bodies, often cup-shaped, called apothecia that release ascospores. The spores must find a compatible photobiont to create a lichen. They depend on each other for resources—from food to shelter and protection.

.

Lichen Reproduction

Lichens spread throughout the environment by reproducing both sexually and non-sexually. Justin Anthony Groves at Whiteknights biodiversity tells us that lichen reproduction: “is no simple matter; only the fungus of the lichen reproduces sexually.”

Lichen Sexual Reproduction:

.

Different lichens may have one or more of several types of reproductive structures. To produce sexually, lichens produce fruiting bodies called ascomata. These ascomata release microscopic mycobiont spores over a long period (months to years). Thousands of spores are ejected from sac-like structures (asci) and dispersed by wind, rain and animals. Each asci contains eight ascospores and may be arranged in a variety of ways in a cup-shaped disc (apothecia), or elongate or script-like lirellae, or globose perithecia structures, the general term being ascocarps. Ascocarps can be immersed in the thallus, on its surface, or stalked. The most common type of ascomata is the apothecium (apothecia) and perithecium. Apothecia are usually cups or plate-like discs located on the top surface of the lichen thallus and formed by the fungus part of the lichen. Spores develop in them and are then forcefully ejected or washed out and dispersed into the environment. One of two things must happen to successfully reproduce this way: the spore must land in a place where its algal partner exists in a free state; the spore may land on another lichen where the fungus (like a parasite) takes over the phycobiont of the existing lichen.

Producing units of dispersal that contain both fungus and alga would assure and speed up colonization of new sites. This is precisely what lichens do in their several techniques of asexual reproduction and propagule dispersal.

Lichen Asexual Dispersal:

In his book “Lichens” William Purvis argues that because the chances are relatively small that an ascospore or conidium of a lichen fungus will germinate extremely close to just the right phycobiont on the right substrate, lichens require mechanisms to bypass spore-based reproduction. Lichens have at least six ways they can disperse without the need for sexual reproduction, including the production of: 1) Fragmentation; 2) Squamules; 3) Isidia; 4) Soredia; 5) Phyllidia and Folioles; and 6) Conidia.

The lichen makes more of itself as fragments of the thallus break off and are often carried off by animals.

.

.

Some lichens have squamules (scales) on their thallus or produce them on structures called podetia (stalks, particularly of Cladonia lichen). The squamules break away to be distributed by animals or wind.

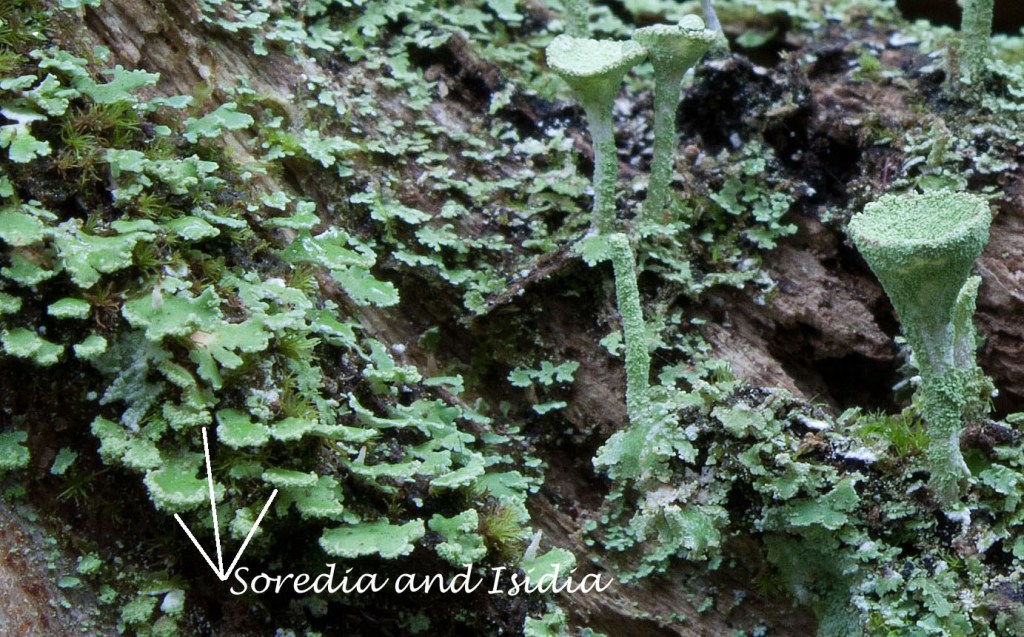

Specialized asexual structures called Isidia (peg-like outgrowths from the upper cortex of the main thallus) or clusters of Soredia (a dust like material usually on the lobe margins that contain algal cells wrapped in fungal hyphae) break off and are transported some distance by wind, rain and animals. Both Isidia and Soredia are bundles of photobiont cells bound up in fungal cells.

.

I saw a good example in the Trent Nature Sanctuary, Ontario, of soredia and isidia in the scaly thallus lobes of Cladonia chlorophaea after a dry spell followed by a light rain.

.

.

Phyllidia are small, leaf-like or scale-like outgrowths from a foliose thallus, constricted at the point of attachment and readily detached and dispersed by wind or animals. Folioles, or lobules, are similar outgrowths though less constricted. Both are considered leaf-like, flattened isidia.

.

.

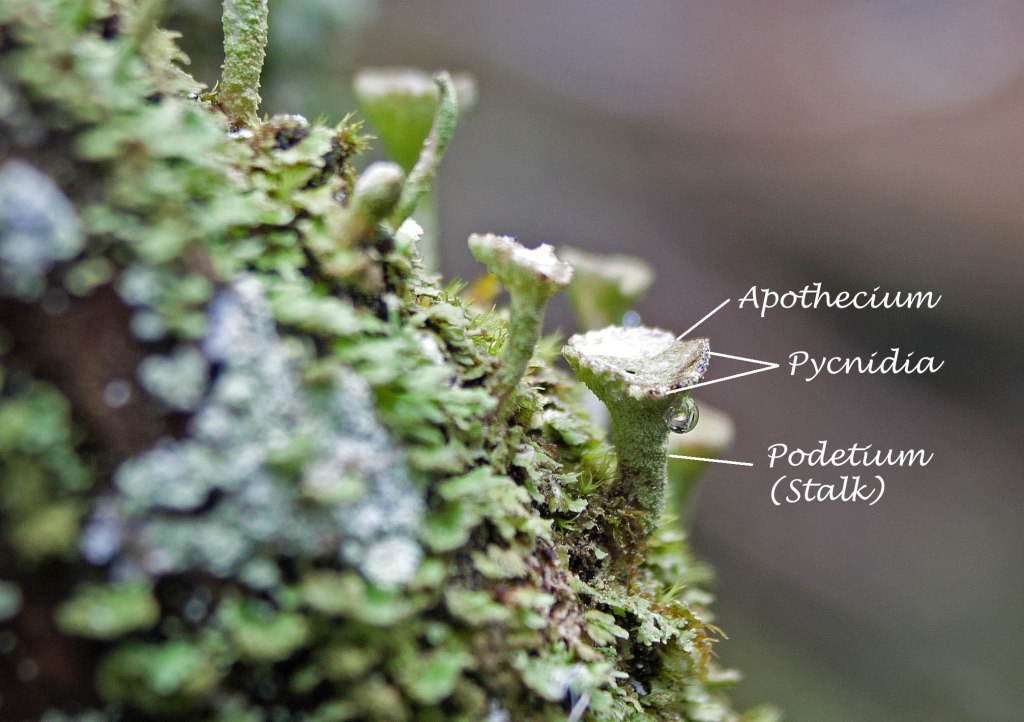

Some lichen (mostly fruticose lichen) produce an outgrowth from the thallus in the form of a stalk or podetium. The Mealy Pixie Cup flask-like stalk bears a cup-like structure, a hymenial disc (apothecium) with pycnidia around its rim. The pycnidia contain conidia which are asexual fungal spores.

.

.

Lichens are known for their very slow growth rate and longevity. Several hundred-year-old lichen are commonly reported. Ages of up to 4500 years were claimed for the crustose Rhizocarpon geographicum in Greenland and Lapland. According to Mason E. Hale, growth of crustose and foliose species usually occurs at the margins, spreading out, and leaving the centre to disintegrate, creating a ‘donut’ shape. The freshly exposed rock surface at the centre is colonized by other lichen, usually from nearby. Fruticose species grow mainly apically with height (erect species) and length (pendent species) increasing with age. Hawksworth and Rose noted that annual radial increments of British crustose and foliose lichen were about 0.5 to 5.0 mm. Fruticose species grow more quickly, achieving 1-2 cm in height or length in a year.

What follows is a description of some lichen I’ve found during my various wanderings in Canada, mostly British Columbia and Ontario. Most are common and together they represent the various forms and habitats lichen use as their home. I’ve grouped them by their form and I’ve colour-coded the titles for each lichen found according to their main habitat (or the one I found them in):

Those found on living or dead trees and biological surfaces are green

Those on the ground are in orange

Those on rock or artificial surfaces such as concrete are grey

Those I found on many types of substrates are titled in black

.

FRUTICOSE: Common Powderhorn—Cladonia coniocraea

.

I found this powderhorn lichen on decaying cedar stumps and logs in the forest swamp of the Trent Forest Sanctuary in the Kawarthas of Ontario. The Common Powderhorn prefer moist and shady habitats. The Common Powderhorn is known to tolerate air pollution and appears to thrive in urban areas.

The Common Powderhorn (Cladonia coniocraea) is fruticose with two types of vegetative (thallus) forms: 1) flat, overlapping leaf-like scales (squamules); and 2) grayish-green slender unbranched stalks (podetia) that taper to a point or a very small cup. The upper two-thirds of the podetia is mealy with the covering of soredia (reproductive cluster of algal cells wrapped in fungal filaments). I saw no disk-shaped apothecia (cup-shaped fungal reproductive structure that produces spores). I’m told they are rare and, if they occur, are brown and sit on the top of the stalk. The Lipstick Powderhorn (Cladonia macilenta) and its cousin British Soldiers (Cladonia cristatella) are a different thing, though…

.

FRUTICOSE: Lipstick Powderhorn—Cladonia macilenta and British Soldiers—Cladonia cristatella

.

Where the Common Powderhorn stalk tapers to an end with a slender glandular cup of the same colour, the Lipstick Powderhorn (Cladonia macilenta) has a finely scaled stalk and several support a blunt red tip, the apothecium. Notice also the extensive squamules along the stalk (podetium) of the Lipstick Powderhorn. The squamules break away to be carried away by rain, wind or animals.

.

.

British Soldiers (Cladonia cristatella), unlike the powderhorns, has much more branching at the tips and lacks the cups of the similar Red Fruited Pixie Cup (Cladonia pleurota). The habitat where I found these lichen—a granitic outcrop with hollows of loose soil, humus and detritus-cover in the Canadian shield—was also identified by field scientists as supporting another branching pixie cup with bright red apothecia, Madame’s Pixie-Cup Lichen (Cladonia coccifera). I was unable to distinguish that species from the similar British Soldiers. Madame’s Pixie-Cup Lichen is most often found in open woods in Canada and the upper Great Lakes on acidic peaty and sandy soils.

.

.

FRUTICOSE: Mealy Pixie Cup—Cladonia chlorophaea

.

The first time I found this lichen was on an old shaded cedar log in a mixed cedar forest. The second time I saw it was on the ground in a sunny place on a river bank in the Kawarthas of Ontario. As with similar trumpet lichen (Cladonia fimbriata), this lichen forms fruticose pale green goblet-shaped splash cups on stalks (podentia) that rise from a patchy scaly mat. The Pixie Cup differs from the trumpet lichen by its wider cup and brownish crenulations (the pycnidia) on the rim of the cups.

Walewski tells us that this lichen grows on wood, bark, rock or soil in full sun or shade. The two habitats I found the Mealy Pixie Cup testify to its adaptability.

.

.

According to Walewski, the splash cups help the lichen reproduce. As rainwater splashes into the cup, spores from the apothecia (specifically, the pycnidia on the rim of the cup) are forcefully ejected, sailing to another place to colonize.

.

FRUTICOSE: Ladder Lichen—(Cladonia cervicornis ssp verticillata)

.

I found this strangely alien-looking lichen growing on Sphagnum-covered rotting stumps in Camosun Bog, Vancouver, BC. This lichen with frilly verruculose fruiting bodies shaped somewhat like golf tees or trumpets (podetia) has smooth splash cups out of which grow more podetia. The splash cups are bordered by bright ruddy brown spore-bearing apothecia which contain pycnidia that release asexual fungal spores called conidia. According to Brodo et al., this lichen is typically associated with boggy areas or other highly acidic habitats.

.

FRUTICOSE: Pebbled Pixie Cup—Cladonia pyxidata

.

The stalks (podetia) of these squamulose lichens form goblet-shaped splash cups with fruiting bodies, reddish-brown tiny ‘blobs’ (apothecia) on their rims. The thalus is grayish-green to olive with primary squamules tongue-shaped. The podetia lack granular soredia and the splash cups have noticeable corticate disc-shaped squamules that look like pebbles, sitting inside. According to iNaturalist, the Pebble Pixie Cup (Cladonia Pyxidata) is most often found on soil, especially acidic mineral soil and thin soil over rocks, more rarely over wood, in mainly arctic to temperate regions.

.

FRUTICOSE: Gray’s Cup Lichen—Cladonia grayi

.

This cup lichen is known to grow on rocks, soils, old woods, heathlands, logs and mosses. I found it inhabiting a granitic rock outcrop on the edge of a forest-marsh. Its goblet-shaped stalk or podetia is greenish to pale grey, usually unbranched and verrucose, often squamulose. Its cup, which can be highly variable, is rimmed infrequently by dark brown apothecia.

.

FRUTICOSE: Gray Reindeer Lichen—Cladonia rangiferina

.

I found cushions of this lichen scattered throughout a rock outcrop and associated forest-marsh. This silver-grey lichen has a main stem that branches like a tree with brownish tapered branch tips and very few with a tiny dark globe that is its fruiting body (pycnidium). Also called reindeer moss, this edible lichen often dominates the ground in boreal pine forests in a wide range of habitats, growing on humus or soil over rock. As the name suggests, this lichen is a favourite food for reindeer (caribou).

.

FRUTICOSE: Thorn Lichen—Cladonia uncialis

.

I found this lichen cozy with the reindeer lichen but spread out more in rounded tufts of pale greenish cushions with many-branched stalks. The stalks were mottled green-yellow and the branch tips were also brown.

.

FRUTICOSE: Rock Foam Lichen—Stereocaulon saxitile

.

I found small clusters of this snow lichen on a sun-exposed granite outcrop, often associated with moss, Pixie Cups and Peppered Rock Tripe. It looked ‘frothy’ from my standing position and it was only when I crouched down for a closer look that I recognized that its ‘froth’ was a dense covering of ‘bubbles’ on the lichen branches. The grey to white tree-like branches that emerged from a woody base were covered in coarse rounded squamules or granules (phyllocladia) that looked like yogurt-covered candies.

.

.

FRUTICOSE: Beard Lichen—Usnea sp.

.

I found this beautiful lichen colonizing a downed poplar tree in the cedar swamp forest in the Kawarthas of Ontario. This lichen formed densely long-branched tufts and is considered pollution sensitive. Usually found high in the crown of trees, its branching form is suggested to reduce drag from the wind. Others suggest that branching has more to do with capturing light and carbon dioxide.

FRUTICOSE: Oakmoss—Everna prunastri

.

I found this lichen on a branch of a red alder tree in British Columbia. Despite its flattened, strap-shaped lobes makes it appear like a folios lichen, it is a fruticose lichen given that it is branched and has a shrub-like or bushy form. Oakmoss forms a pale grey-green to yellow-green bushy thallus that is palmately (hand-like) branched. Oakmoss grows on the bark of trees and shrubs, particularly oaks, but also on conifers and other deciduous trees. It can be found in many mountainous temperate forests throughout the Northern Hemisphere.

.

FRUTICOSE: Dragon Horn Lichen—Cladonia Squamosa

.

I found this pale grayish-green lichen closer to the forest, in the shallow litter-covered mossy soils of Catch Rock, enjoying the shade of hemlocks and oaks. Its highly squamulosed sparingly branched stalks arose from a sea of pale green scales. Its podentia sometimes carry tan to brown fruiting structures at the tips, which I did not see. The Dragon Horn is most often observed in shady moist forests, where I found it.

.

.

FOLIOSE: Many-Fruited Pelt Lichen—Peltigera polydactylon

.

I found this lichen growing among moss on rocks and boulders and the ground in several mixed cedar forests in the Kawarthas of Ontario. Peltigera’s dark olive-grey colour comes from the photobiont, which is the nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria Nostoc. This lichen spreads an undulating foliose brown mat (thallus) that forms upturned lobes with lighter saddle-shaped red-brown projections (apothecia). “As the name implies,” writes Walewski, “there are many fruiting bodies—apothecia—on the lobe margins.” Others describe these projections of the thallus into apothecia as fingers with bright red-orange to reddish-brown varnished finger nails. These apothecia are the reproductive structures for the fungal component or mycobiont. The tiny spores are released from the apothecia and fall to the ground and if they encounter the free-living cyanobacteria Nostoc they will then grow into a new lichen. As I mentioned before, this seems a touch and go way to reproduce. Luckily the pelt lichen has more ways to reproduce.

I noticed Phyllidia and Folioles or “lobules” on the edges of the lobed thallus as well as what might have been Isidia (specialized outgrowths) and clusters of Soredia on the edges for easy dispersal. All of these asexual modes of reproduction provide all that’s necessary to grow another organism.

.

FOLIOSE: Common Greenshield Lichen—Flavoparmelia caperata

.

I found this large foliose lichen dominating the branches that had fallen from at least twenty metres above the ground during a spring ice storm in the Mark S. Burnham old-growth forest. The pale yellow-green corticolous Common Greenshield Lichen (Flavoparmelia caperata) formed fist-sized circular patches that wrapped right around the branch. Known to grow on bark of all kinds in sun or partial shade, this very common lichen is often the first to return following complete loss of lichens.The lobes of most specimens I saw were wrinkled, showing their age.

.

FOLIOSE: Star-Rosette Lichen—Physcia stellaris

.

I found this lichen on several Poplars, Elms and Buckthorns in the mixed forests and open thickets of the Kawarthas. They occurred mostly on branches and twigs. As the name suggests, the thallus forms a foliose rosette-shape that contains small dark brown disks (apothecia) that carry spores.

.

.

.

FOLIOSE: Frosted Rosette Lichen—Physcia biziana

.

I found Physcia biziana colonizing a red maple on a suburban street in Peterborough, Ontario. P. biziana turns a deep sea-green with more marked maculae when wet. Aside from being larger, its marked colour change and highly maculated thallus distinguishes P. biziana from its sister Physcia stellaris.

.

FOLIOSE: Hooded Rosette Lichen—Physcia adscendens

.

This strange looking green-grey foliose lichen distinguishes itself with ostentatious inflated pale helmet-shaped hoods (soralia that contain cream-coloured soredia) on raised lobes. Another distinguishing feature are the long white dark-tipped hairs (cilia), curly ‘whiskers’ that extend out from the tips of its lobes. When wet, Physcia adscendens takes on a deeper green Mediterranean Sea colour, showing more marked white mottling (maculae) on the thallus.

.

FOLIOSE: Mealy Shadow Lichen—Phaeophyscia orbicularis

.

This common foliose lichenvspreads across tree bark and other surfaces, usually in well-lit, nutrient-rich environments. Its orbicular lobes are elongate, spreading out often in a rosette and covered in soralia that produce powdery soredia (asexual reproductive structures) usually closer to the centre of the rosette. When dry this lichen is dark grey with slightly lighter grey edges. When wet, it turns dark olive green with brighter green edges.

.

Foliose: Pom Pom Shadow Lichen—Phaeophyscia pusilloides

.

I found this grey-green to darker olive green Pom Pom Shadow Lichen (Phaeophyscia pusilloides) growing on many trees including the ash, poplars, maples, beech trees, oaks, ironwoods and birches. Rosettes of this foliose lichen varied from tiny 1 cm to chaotic spreads of 10 cm in diameter.This delightful pale olive lichen is distinguished by long narrow lobes and the thick curly black rhizines that extend beyond the lobes, resembling mascaraed eyelashes (also see Joe Walewski’s Lichens of the North Woods). Phaeophyscia pusilloides goes by the common name Pom Pom Shadow Lichen because of its pom pom-like appearance; though I just don’t buy it. Maybe I’m just not a pom pom kind of person…

.

Foliose: Mealy Rosette Lichen—Physcia millegrana

.

I first found scattered small patches of this frilly blue-grey foliose lichen on a fence post in Ontario then on the main trunk of a red maple tree, often adjacent to Xanthoria fallax. When dry, Physcia millegrana has a pale gray thallus, spotted with white maculae. Its lobes are thin, highly dissected with margins thick with granular soredia. Apothecia (sexual reproductive structures) are also frequent, with lecanorine margins and dark brown-bluish pruinose disks. This highly successful lichen uses both sexual (apothecia) and asexual (pycnidia and soredia) reproductive strategies.

P. millegrana is a pioneer species, frequently the first to colonize stems and branches of young woody plants. Its preferred habitat is exposed bark in a forest or human altered habitat. P. millegrana is a very common lichen, often dominating urban settings and described as the most pollution-tolerant macrolichen in eastern North America. Ways of Enlichenment report finding it on various deciduous trees including the American Sycamore, and even exposed rock.

.

FOLIOSE: Hammered Shield Lichen—Parmelia sulcata

.

I found this foliose pale gray-green lichen colonizing an old birch log in a cedar forest on Ontario. Its thallus is dimpled with depressions and lower surface is black with unbranched rhizines. Shield lichen may be the most common lichens in the Kawarthas. They are the first organisms to colonize trees (and even picnic tables!). Ruby-throated hummingbirds are known to camouflage their nests with bits of Parmelia.

.

FOLIOSE: Monk’s Hood Lichen—Hypogymnia physodes

.

I found this foliose tube lichen on an old red alder tree in British Columbia. Also called Hooded Tube Lichen, it is common and widespread in boreal and temperate forests. When dry, its thallus is grey to yellowish-green and loosely attached to its substrate. When wet, the thallus turns a deep sea-green as the algal partner actively photosynthesizes. The hollow lobes, often brownish toward their margins, are often turned up and covered in white powdery soredia. The lower part of the thallus is black. This lichen also has abundant tiny black pycnidia, looking like pepper on the upper thallus.

.

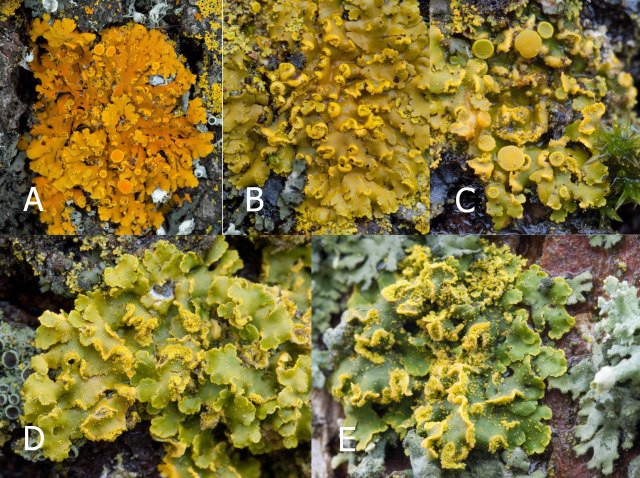

FOLIOSE: Hooded Sunburst Lichen—Xanthoria fallax

.

Like a clarion call, each large rosette of this deep orange-yellow lichen seemed to call to me: I’m so bright like the sun! Look at me! So, I did. This foliose lichen can get large, often the size of my fist. The lobes of Xanthoria fallax are flat to convex and raised along the margins between the upper and lower cortices where crescent-shaped bird’s nest-like soralia (chambers carrying powdery soredia) carry greenish-yellow powdery soredia (asexual reproductive structures).

In the dry this foliose lichen forms orange-yellow rosettes all over a tree trunk and rough bark, dominating the tree trunk and branches with splashes of colour. I found this lichen mostly on maples, but also saw it on ash, elm, poplar and oak. It likes nutrient-rich bark and colonizes many deciduous trees. When wet, the lobes of Xanthoria fallax turn greenish; but the powdery soredia on the edges form a bright contrast with their startling yellow colour. Colonies may have brightly coloured lecanorine apothecia (sexual disk-like fruiting bodies) with the disk considerably darker than the thallus.

.

FOLIOSE: Candleflame Lichen—Candelaria concolor

.

I found chaotic rosettes of this tiny but bright yellow (when dry) lichen scattered everywhere on a red maple trunk and branches of the street in Ontario where I lived at the time. At first, I thought they were tiny immature versions of the sunburst lichen, but closer examination revealed that this finely branched foliose lichen was its own species. When the sunburst lichen turned a deep orange during dry conditions, this little lichen remained bright lemon yellow. During wet conditions, both lichens demonstrated green to yellow-green thalli that were actively photosynthesizing. Yellow granular soredia are common, particularly on the lobe margins and at times so dense to obscure the lobes.

.

FOLIOSE: Cumberland Rock Shield—Xanthoparmelia cumberlandia

.

I saw this yellowish-green lobed foliose lichen tightly attached to a granitic rock outcrop on the edge of a forest marsh in Ontario. The shield lichen formed large radiating patches with brown discs crowding the centre. The leading lobes were typically more pale and had a light bluish hue to them. The brown discs (apothecia) vary in size. Walewski notes in his book that apparently lichens with larger apothecia are more successful. This lichen is known to grow on exposed to somewhat shaded rock outcrops and boulders.

.

FOLIOSE: Peppered Rock Tripe Lichen—Umbilicaria deusta

.

I found patches of this strange dark brown lichen with granular isidia-rich lobes throughout much of Catch Rock’s exposed surface. Its texture looked quite different when wet and when dry. This lichen isknown to enjoy siliceous rocks such as granite and gneiss and is often seen on exposed rock outcrops where it can withstand less moisture.

.

.

CRUSTOSE: Whitewash Lichen—Phlyctis argena

.

Whitewash Lichen is well-named for resembling a dull white wash of paint. This crustose lichen forms large patches throughout younger trunk and branches of trees where the bark is smoother. At first, I mistook Phlyctis argena for the actual bark of a red maple tree branch, these being concentrated on the smaller branches of the tree, much like a poplar tree will show smooth bark in its younger trunk and branches. But with closer inspection, I knew it was some kind of thin crustose lichen.

This generalist epiphyte grows on the bark of many deciduous trees and is reported particularly on willow, ash, oak, and red maple, even cedar. Phlyctis argena is known as being acidophyllic and tolerant of air pollution.

.

CRUSTOSE: Fluffy Dust Lichen—Lepraria lobificans (finkii)

.

The bark of several trees in the Ontario Kawartha forests were covered in colonies of Fluffy Dust Lichen, including oak, poplar, cedar and ash trees. As the name suggests, this dust lichen resembles green-gray granular dust or powder is if “spray-painted” on the tree bark. This lichen is common on many tree bases as well as shaded rock. If you’re lucky you may see dull, even, or wrinkled soredia.

.

.

Fluffy Dust Lichen is widely distributed in the world and likes to grow on soil, over mosses, on bark where I see it most of the time, in moderately shaded and dry areas and on rock overhangs.

.

CRUSTOSE: Mapledust Lichen—Lecanora thysanophora

.

Many of the sugar maples in the Kawartha forests are colonized by this crustose lichen. The best example of Mapledust’s yellowish-green fuzzy-dusty mat can be found on the smooth bark of a young maple tree. Mapledust (which also colonizes beech, oak and basswood, can be distinguished from Dust Lichen (Lepraria) by its white webby margin. The white edges are the fungal partner and the granular green surface are largely the algal partner. As the maple tree ages, its bark starts to ooze alkaline, nitrogenous compounds; these altering conditions create a more diverse community of lichen and mosses.

.

CRUSTOSE: Common Script Lichen—Graphis scripta

.

This strange crustose powdery lichen that resembles the fluffy dust lichen is characterized by and gets its name from the darkish strange squiggles that resemble short scribbles looking like a secret alphabet on the thallus. the dark squiggles of this graphid lichen are actually elongated and narrow spore-producing apothecia. I found this lichen on a young beech tree in an old-growth hemlock forest in Ontario. These lichens start rather inconspicuously as grey smears on a tree; eventually the grey thallus develops visible squiggles of apothecia that look like a pair of lips, called lirellae. The script lichen prefers the smooth bark of a beech tree or young red maple or alder on which to ‘write’ its story.

.

.

CRUSTOSE: Fairy Puke or Candy Lichen—Icmadophila ericetorum

.

I discovered this lichen in Camosun Bog, Vancouver, the area covered in mounds and hillocks of Sphagnum and other mosses, growing on rotting logs and stumps and peat. This ‘dusty’ blue-green thallus with pink ‘disks’, which are the fungal fruiting bodies (apothecia), is a colourful addition to an environment. Another common name for this crustose lichen is Candy Lichen or Peppermint Drop, not as imaginative as the former.

.

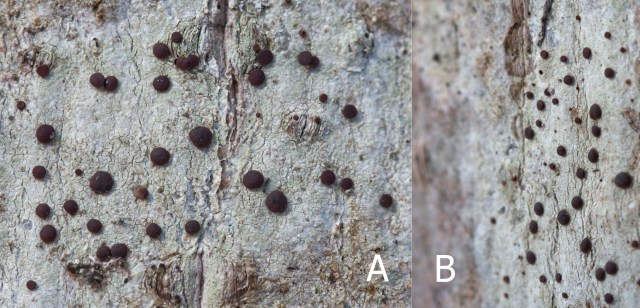

CRUSTOSE: City Dot Lichen—Scoliciosporum chlorococcum

I noticed large patches of a green highly granulated crustose lichen with noticeable blue-black half-spheres at the base of Maple #3 and #4. I then observed small scattered patches on the other Maples. The blue-black fruiting bodies (apothecia) embedded in the granular green thallus start out as flat ‘disks’ then grow into round convex ‘half-spheres.’

I first identified this beautiful lichen as Bark Disk Lichen (Lecidella euphorea) or Lecidella elaeochroma. But further research and observation indicated a better fit for City Dot Lichen (Scoliciosporum chlorococcum), based on its characteristic dark green irregularly granular thallus and large blue-brown convex apothecia. These two similar-looking crustose lichens otherwise share the same type of habitat, colonizing damp, shaded, nutrient-rich bark, often wood and even rock.

.

CRUSTOSE: Common Button Lichen—Buellia erubescens

.

On several maples, oaks and poplars in local Ontario forests I saw many 2 to 12 cm patches of whitish-greenish crustose lichen, spreading like paint splashes over smooth or crusty bark, and dotted with dark, almost black, ‘buttons.’ This is the Common Button Lichen (Buellia erebescens), a crustose lichen often found on conifers and oaks and other trees with bark of generally low pH. Others have reported seeing the Common Button Lichen on red maple (Acer rubrum), where I first saw this lichen.

.

CRUSTOSE: Bark Barnacle Lichen—Thelotrema lepadinum

.

I found this corticolous lichen growing on the fairly smooth bark of an old red alder tree in coastal British Columbia, looking like barnacles on a creamy grey-white crusty thallus. The apothecia of this crater lichen really look like barnacles, with a thick outer rim and a thin papery inner rim. Barnacle lichen thrive in humid, oceanic environments of the Pacific Northwest. Several sources say that this lichen is normally found on tree bark of longstanding woodlands.

.

CRUSTOSE: Smooth Saucer Lichen—Ochrolechia laevigata

.

I found this saucer lichen, also called Crabseye Lichen, on an old red alder tree in coastal British Columbia. The lichen typically has a smooth, white to greyish thallus with distinctive pimples’ of the spore-producing apothecia scattered throughout its surface. The apothecia are saucer-shaped disks of yellow-brown to orange rimmed by lighter margins. This lichen seems to prefer alder, but can also be found on vine maple and some other deciduous trees.

.

CRUSTOSE: Yellow Map Lichen—Rhizocarpon geographicum

.

I found this interesting crustose yellow-green lichen with black dots on the surface of a granite outcrop in the marsh of Catchacoma Forest in Ontario. It is normally found on silicate rocks. William Purvis describes them as “minute yellow green islands, which contain the pigment rhizocarpic acid, growing on a black layer lacking algae.”

.

CRUSTOSE: Single-spored Map Lichen—Rhizocarpon disporum

.

I found this crustose lichen throughout a granitic rock outcrop, particularly its sun-exposed area. This olive to brownish gray lichen with black apothecia resembles a congregation of tiny gray-green-brown pebbles with darker, close to black, warts. This lichen grows on sun-exposed siliceous rock, including Pre-Cambrian granite.

.

CRUSTOSE: Cinder Lichen—Aspicilia cinerea

.

I discovered this strange and wonderful lichen on a granitic rock outcrop in a marsh-forest in Ontario. Gray to almost white, this areolate lichen, with large black apothecia, is known to inhabit siliceous, schist or igneous rock exposed to sunlight.

.

CRUSTOSE: Rock Disk Lichen—Lecidella stigmatea

.

I found colonies of this lichen spreading throughout the sun-exposed surface of Catch Rock, a granite outcrop. It has a dirty white to grey areolate thallus and flat to convex black disks (apothecia). This ubiquitous lichen grows on both non-calcareous and calcareous rock. I originally identified a patch of this lichen as Tile Lichen (Lecidea tesselata), because it likes granite, thrives in full sun, and looks similar. However, the black disks of Tile Lichen are sunken in the thallus and not overtopping the areoles, and its thallus appears more tile-like, particularly when dry.

.

CRUSTOSE: Tile Lichen—Lecidea tessellata

.

I found this crustose lichen with flattened black disks on the sun-exposed flat of a granitic rock outcrop. This lichen is known to inhabit granite rock. It has a chalky white to grey areolate thallus with black apothecia that are either subimmersed, appressed or adnate. The black apothecial disk of Lecidea tessellata is smooth and initially rounded when young, becoming convex and irregular at maturity.

.

.

CRUSTOSE: Chewing Gum Lichen—Lecanora muralis

.

I found this beautiful rosette-forming lichen, with lecanorine apothecia and tan disks, spreading over the exposed top surface of a granite outcrop in loose rosettes with leafy-like lobes. This cosmopolitan lichen grows on a variety or rock types from granite to limestone. When dry, the thallus formed pale green areolate ‘lobes’; when wet, the thalli looked more green with polyphyllous squamules. As the name suggests, this lichen likes granite.

.

CRUSTOSE: Granite-speck Rim Lichen—Lecanora polytropa

.

Granite-speck lichen is granite-loving and very similar to its cousin Chewing Gum Lichen (Lecanora muralis). I saw this species colonizing sun-exposed areas of a granite outcrop; the patches I observed were more chaotic, less rosette-formed, and lacked the foliose-looking lobes of its more squamulosed neighbour, the Chewing Gum Lichen.

.

CRUSTOSE: Zoned Dust Lichen—Lepraria neglecta

.

As the species name of this lichen suggests, this tiny granular fuzzy lichen that looks like so much dust, is often neglected because of its diminutive size and chaotic presentation. Walewski writes that dust lichen “are nothing more than a continuous layer of granular soridia.” Zoned Dust Lichen commonly grows on partially shaded granitic rock; I found it hiding among more robust lichen on a rock face, both shaded and exposed to the sun. Once established, Zone Dust Lichen often forms distinct rings.

.

BIRCH LICHEN COMMUNITY

.

Remembering what Walewski said about the single sugar maple, I noticed the diverse lichen and moss community on an old white birch tree in the Trent Nature Sanctuary cedar-birch forest. I noticed several different lichens and several mosses in different stages of growth. As I strolled out of the dense forest that day, I reflected on Nature’s fractal arrangement: peering closer at the birch bark encrustations, I saw how like a miniature forest—its own universe—this bark community was. Complete with lichen, moss, fungi, algae and various foraging creatures. It was an entire functioning ecosystem.

The more you look, the more you see.

.

.

.

References:

Andre, Alestine and Alan Fehr. 2002. “Gwich’in Ethnobotany,” 2nd ed. Gwich’in Social and Cultural Institute and Aurora Research Insitute. 68pp.

Brodo, Irwin M., Sylvia Duran Sharnoff and Stephen Sharnoff. 2001. “Lichens of North America.” Yale University Press, New Haven. 795pp.

Gilbert, O., 2000. “Lichens.” London: HarperCollins

Hale, Mason E. 1967. “The Biology of Lichens.” Edward Arnold Ltd., London. 176pp.

Hawksworth, David L. and Francis Rose. 1977. “Lichens as Pollution Monitors” Edward Arnold Ltd., London. 60pp

Lastdragon.org. 2021. “Images of British Lichens: FAQ.” Online: http://www.lichens.lastdragon.org/faq/lichen_asexual_dispersal.html

Nash III, H.T., 2010. “Lichen Biology”. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press

Purvis, William., 2000. “Lichens.” Natural History Museum, London. 112pp.

Ryan, B.D., Bungartz, F., & Nash III, T.H. (2002). Morphology and anatomy of the lichen thallus, in Nash III, T.H., Ryan, B.D., Gries, C., & Bungartz, F. (eds.) Lichen flora of the Greater Sonoran Desert Region, vol. 1, Arizona State University, Tempe, pp. 8–23.

Smith, C.W., Aptroot, A., Coppins, B.J., Fletcher, A., Gilbert, O.L., James, P.W., & Wolseley, P.A. (eds.) (2009). The lichens of Great Britain and Ireland, British Lichen Society, London.

Walewski, Joe. 2007. “Lichens of the North Woods.” Kollath & Stensaas Publishing, Duluth, MN.

.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

.

Hello! I was half-heartedly trying to ID a lichen someone posted in a FB group, and stumbled upon your post. What a great article, very dense with info and very readable! Thank you! I’ll be sharing this often, I’m sure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, Lisa. Yes, do come back. I post weekly with interesting articles on the environment, and on water phenomena, particularly. All the Best, Nina

LikeLike

Hi-

I’m wondering if you have any zoom lectures that would be interesting to garden club. Your pictures and text above are wonderful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Sandy. I don’t have any zoom lectures but thanks for your interest and letting me know you liked the pictures and text. Lichen are incredible organisms! Best, Nina

LikeLike

The more you look, the more you see! Thanks for the informative article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed it. Best,

Nina

LikeLike

I mean just Oh My God! Really the best article I found while just randomly running my hands on the keyboard. I myself am a lichen lover too and this article just took me one step closer to this diplomatic organism. It really helped me and the pictures made me just awestruck. Good content so far. I hope that can u just have a one article based on the pH profiling of the lichen w.r.t to its bark. That’s a request. If in future someday u can do it so I’ll be waiting for that article too.

well thanku till then Maam.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Neha Pantola! Thanks for your comments. You talk about pH profiling of lichen … very fascinating. I’ll see what I can do about another article. Lichens are so incredibly interesting. But have patience… It may take a while …

All the Best,

Nina

LikeLike

Hi Neha Pantola! I just wanted to notify you of my recent article called “The Lichen Forest of Catch Rock”, which I think will interest you. It’s all about saxicolous lichen colonizing an acidic granite outcrop. Here’s the link to the article: https://themeaningofwater.com/2024/12/01/the-lichen-forest-of-catch-rock/

LikeLike