It was a fresh morning in mid-September and I was walking in the riparian forest along the Otonabee River, south of Trent University and close to Thomas A. Stewart Secondary School. Accompanied by the mellifluous song of the Warbling Vireo, my walk led me to a small alcove of river shoreline with three large rocks where I normally get a good view of the river.

Today, floating globs of filamentous algae formed an archipelago of bright green islands amid the rocks. The water level was particularly low and green algae carpeted the exposed stones with slime that smelled of dead fish (the Otonabee is a regulated river with over five dams along it to generate electricity).

I looked across the river to the opposite shore and watched cars and trucks lumber along Water Street, located just metres from the river bank in some places. I noted that while much of the shoreline had remained natural marsh, sections of shoreline were rip-rapped or paved or stone foundations had been built right to shore. Riparian properties had done various things to alter or modify the shore from its natural marsh or cobble and sand banks. Farther along in my walk, I noticed a profusion of floating green mats in the small bay just south of where Thompson Creek enters the Otonabee River. On my way back to the house, I collected some algae from shore and identified the community under the microscope. The mats consisted mostly of Zygnema sp. and Spirogyra spp., two filamentous algae belonging to the Chlorophyta whose blooms can indicate over-fertilization or organic enrichment—often by contaminated stormwater runoff. The filamentous algae were accompanied by a diversity of diatoms and various microscopic fauna.

On Armour Road, a kilometre upstream from where I stood, is a sign that says: “Drinking Water Protection Zone.”

Apart from this demure sign on the side of the road, there is no indication that the Otonabee River, which runs right through the City of Peterborough, is the source of drinking water for the City.

In early spring this year, when I encountered several local high school students in the river’s eastern riparian forest, I asked them if they knew that the Otonabee River was their drinking water source. The students all said “no”; they had no idea. Most stared at me, ignorant and, for the most part, unimpressed.

I found the disconnect between the sign’s warning and the community’s ignorance disturbing, but not surprising. Apart from that little passive sign by the road, what was the city actually doing to protect their drinking water source and how were they involving the community?

In my over 30-year experience as a practicing limnologist, I’ve not seen the passive use of a sign as a sufficient measure to exact protection. What was the city doing besides using a sign to educate its community in appropriate riparian and watershed practices? Was the high school, located right by the river, educating its students in this matter?

Drinking Water Source Protection

Surface drinking water intakes like the one in the Otonabee River require that the surrounding water and the land surrounding the water are protected. This area of water and land is known as an Intake Protection Zone, or IPZ. Protecting it ensures a healthy supply of water now and in the future.

The Intake Protection Zone (IPZ) for Otonabee River drinking water extends about 7 km upstream of the drinking water intake pipe, which is located about 2 m below low water level at the Riverview Park & Zoo. The IPZ appears to extend several meters from the river’s high water mark (I’m guessing from the map) and incorporates portions of major tributaries into the river.

Despite the treatment system being a full conventional treatment process (involving coagulation, flocculation, sedimentation, filtration, and disinfection) the Otonabee Region Conservation Authority lists activities that can still pose a threat to the municipal drinking water source. These include livestock grazing, pasturing, and confinement; road salt use; spreading or storing of agricultural materials (e.g. manure); pesticide and fertilizer storage and use; liquid fuel storage (e.g. home heating oil); and chemical handling and storage.

Increased temperatures and higher nutrients in river sections behind the dams lead to increased biomass of certain diatoms and the proliferation of filamentous green algae (e.g. Ceratophylum, Spirogyra, Zygnema, and Mougeotia—all currently blooming in the Otonabee River along with the diatom forests. These are also responsible for taste and odor of Otonabee drinking water during the summer months. While not harmful, the T&O compounds are detectable even at extremely small concentrations (e.g. parts per trillion).

Urban Runoff in the Otonabee River

Peterborough Utilities Group acknowledges that as rainwater “flows over lawns and roads into storm sewers and then directly into local waterways [it carries] with it dissolved pesticides, salts, oil, and other untreated waste products. Faulty septic systems adjacent to the water course and waterfowl living in the Otonabee River also contribute pollution.”

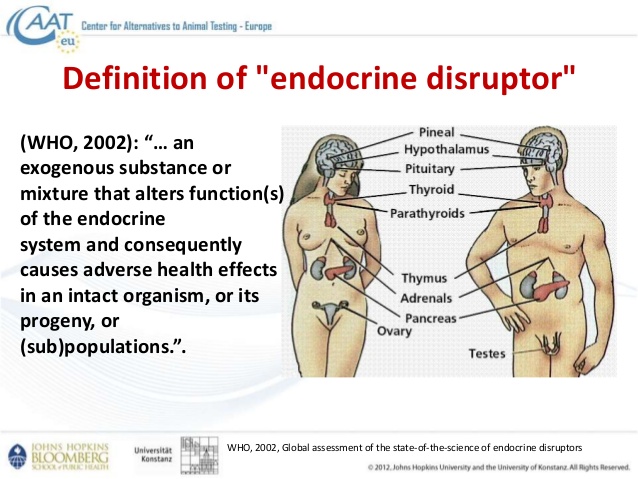

Urban runoff flushes oil, grease and toxic chemicals (such as PCBs, PAHs, heavy metals and other hormone disruptors and carcinogens) from vehicular traffic and construction into our waterways. Unchecked urban runoff may provide contamination by heavy metals, PAHs, PCBs, pesticides, herbicides and other hormone disrupting chemicals. While the treatment process at their water treatment plant effectively treats most of these, the taste and odour linger, along with some turbidity and other residuals.

In their 2016 report card of the Otonabee River, Otonabee Conservation gave the river a C-grade (fair) for water quality, based on phosphorus (nutrient) content and benthic invertebrate populations.

Citizen Responsibilities in IPZs

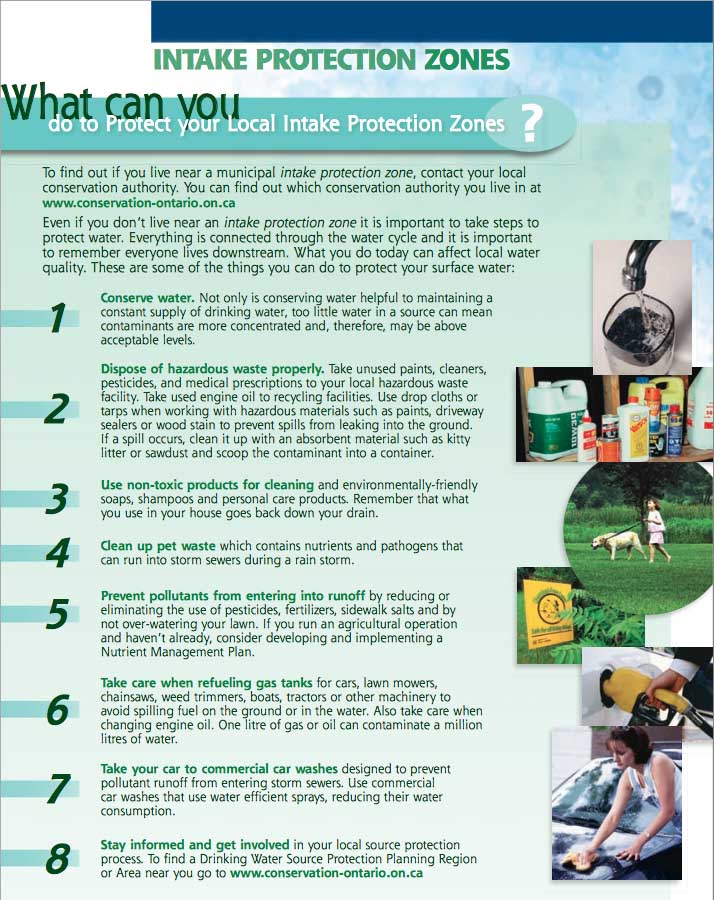

Conservation Ontario’s excellent pamphlet on “Intake Protection Zones” describes eight ways citizens can protect drinking water at the source: conserve water; dispose hazardous waste properly; use non-toxic products for cleaning; clean up pet waste; prevent pollutants from entering into runoff; refuel gas tanks carefully; take your car to commercial car washes; stay informed and vigilant.

Drinking Water Myth

An excellent pamphlet by Conservation Ontario provides four key myths many people hold about their drinking water that put our drinking water quality at risk. I want to explore the fourth myth, because it focuses on our behaviour near any water source (e.g. along the Otonabee, which provides the drinking water for the City of Peterborough). The myth is that “we don’t have to protect sources of water, since we already treat water and make it clean enough to drink.”

The City acknowledges that its treatment systems do not remove all contaminants from water, particularly chemicals.

Municipal water treatment is just one aspect of a ‘multi-barrier approach’ to protect drinking water and of itself does not fulfill all criteria for protecting precious drinking water.

An important aspect of protection remains at the source, in the river or lake basin, through riparian protection, regulation of emissions and outflows, individual stewardship, and continued vigilance by citizens.

What Is Going Into the Otanabee River?

During my daily walks along the Otonabee River, I have noted questionable smells of oil and gasoline in this small stream and I’ve seen rocks covered in an oily sheen; I’ve witnessed brown residue that covered the rocks along with copious brown froth, and a strange milky substance last year; refer to my article on the pollution of a small storm sewer intake stream that fed into the Otonabee.

All these questionable substances flow into the Otonabee River. When I investigated a sample through the microscope of the periphyton community on the muddy rocks of this stream, I noted lots of diatoms such as Nitzchia, Synedra, Fragilaria, Gomphonema parvulum, Navicula, tube-building Cymbella (all tolerant of pollution) occupying a muddy mat that gave off bubbles of oxygen. I identified the dark green film as filamentous Lyngbya sp. (a blue-green alga tolerant of pollution and organic enrichment) along with Oscillatoria (another blue green also tolerant of pollution, including organic enrichment and various toxic elements such as heavy metals; this cyanobacteria is also a known harmful alga).

Without continued vigilance, we run the risk of individual and corporate noncompliance and outright cheating at the expense of our health. Refer to my article on what happened to Parkersburg residents whose Ohio River drinking water was secretly contaminated for decades with toxic chemical PFOA by DuPont’s Washington Works plant. Of course, that river water was treated for drinking; but that treatment didn’t prevent the chemicals from causing cancer and other endocrine disrupting health effects in that community.

The Otonabee River is an unprotected water source. What this means is that the community is permitted to make use without major restriction of its watershed right up to its shoreline, which includes the riparian zone (that encompasses land from shore to 10 to 20 m out). But this comes with great responsibility and that must start with awareness.

References:

Otonabee Conservation. 2018. “Otonabee Region Watershed Report Card 2018.” Otonabee Conservation.

Palmer, Marvin C. 1959. “An Illustrated Manual on the Identification, Significance, and Control of Algae in Water Supplies.” U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Cincinnati, Ohio. 98pp.

Watson, Susan and Friedrich Jüttner. 2019. “Biological production of taste and odour compounds.” In: “Taste and Odour in Source and Drinking Water: Causes, Controls, and Consequences”, Chapter 3. IWA Publishing 63-112pp.

Nina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times ‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020.

3 thoughts on “The Paradox of The Otonabee River: Unprotected Drinking Water Source”